[/caption]

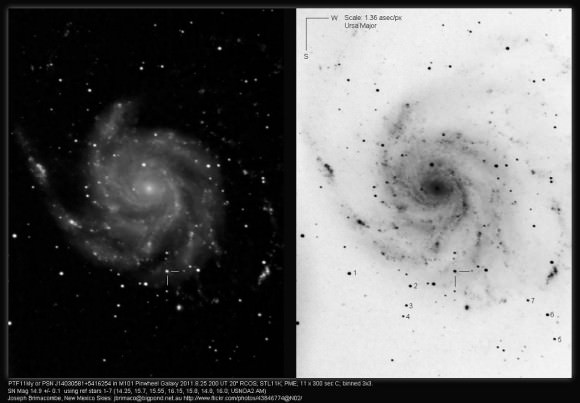

Here at Universe Today, we’ve been providing plenty of coverage on the recent supernova in spiral galaxy M101 (AKA Pinwheel Galaxy). Readers have uploaded their images to our Flickr page and have been asking about the event, weeks after it was detected.

While the supernova has been dimming since its peak brightness, most supernova events brighten quickly, but fade slowly. This supernova is by no means visible with the naked eye, but here’s what you need to know to catch a glimpse of the brightest supernova in the past few decades.

First a short primer on M101: Nicknamed the “Pinwheel Galaxy” for its resemblance to the toy, M101’s distinct spiral arms can be imaged with modest amateur astronomy equipment. M101 is about six megaparsecs ( 1 parsec is just over three and one-quarter light years ) away from our solar system, which is over six times more distant than our closest neighbor, the Andromeda Galaxy. M101 is a galaxy that is much larger than our own galaxy – nearly double the size of the Milky Way.

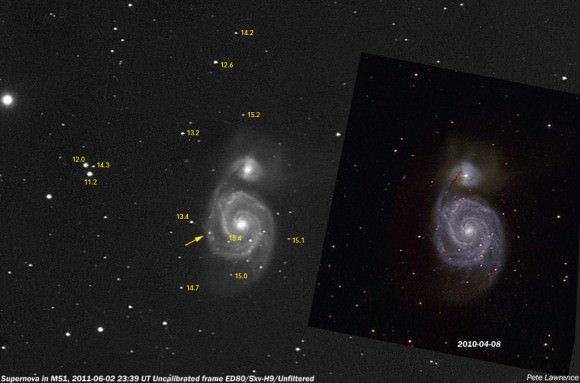

What made M101 newsworthy as of late was the Type Ia supernova discovered inside the galaxy. Discovered nearly a month ago on August 24th, SN 2011fe (initial designation PTF 11kly) started off at around 17th magnitude and recently peaked around magnitude 10 (magnitude 6-7 is limit of “naked-eye” visibility with dark skies).

Scientists and amateur astronomers alike have scrambled to gather data on SN 2011fe. Some observers have even looked through data collected in late August only to see they captured the supernova without knowing it!

By mid-September, though, SN 2011fe has become too faint for casual observers to see, but experienced amateur astronomers can still see it with telescopes. If you don’t have a good-sized “amateur” telescope, you might consider contacting a local astronomy club to see if they are having a “star party” or observing night in your area. To find an astronomy club, check out NASA’s Night Sky Network.

Viewing M101 and SN 2011fe isn’t terribly challenging, so long as you have a decent view to the North. You can find M101 by using the Big Dipper asterism (Ursa Major for the constellation purists). Look for the last two stars of the Big Dipper’s handle (Mizar and Alkaid). Above the midpoint between the two stars is M101. For those with motorized telescopes, start at Mizar, slew a little to the east and up a little. People who are lucky enough to have a computerized, “Go-To” scope can enter the RA and Dec coordinates of 14:03:05.81 , +54:16:25.4.

This week you’ll want to try viewing M101 in late evenings, otherwise you may find it too close to the horizon and washed out by the waning gibbous Moon. To your eyes, M101 will appear as a fuzzy “smudge” in the eyepiece. If you are at a very dark site and use averted (looking slightly to the side of the object) vision you might see some detail with a 12″ or larger telescope. You can certainly view M101 with a telescope as small as 6″, but you really do want to view M101 with as big of a telescope as possible. Don’t use higher power eyepieces to try and make up for a small telescope. Many galaxies, including M101 are best viewed with mid-to-low power eyepieces.

Below is an image generated by Stellarium. In the image are a few constellations and some guide stars you can use to guide your eyes and telescope to M101.

Clear skies and good luck!