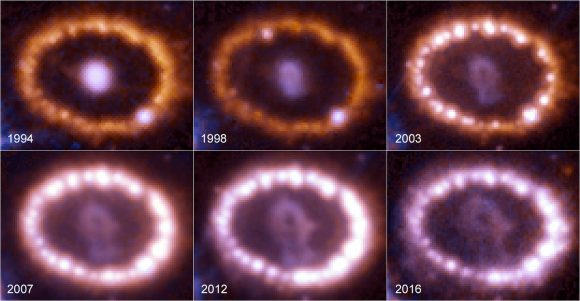

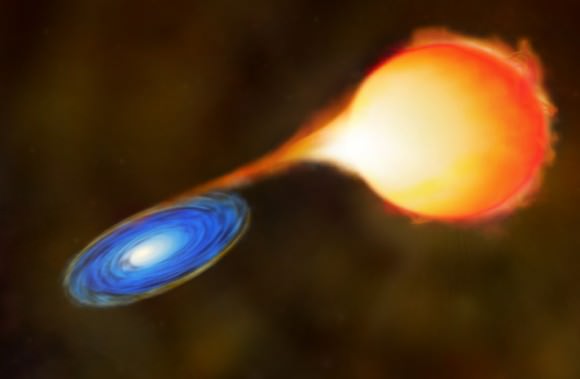

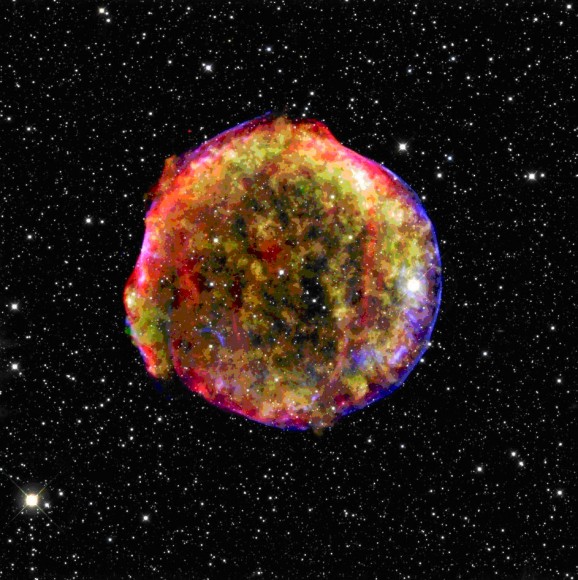

A supernova is a rare and wondrous event. Since these intense explosions only take place when a massive star reaches the final stage of its evolutionary lifespan – when it has exhausted all of its fuel and undergoes core collapse – or when a white dwarf in a binary star system consumes its companion, being able to witness one is quite the privilege.

But recently, an international team of astronomers witnessed something that may be even rarer – a supernova event that appeared to be happening in slow-motion. Whereas supernova of its kind (SN Type Ibn) are typically characterized by a rapid rise to peak brightness and a fast decline, this particular supernova took an unprecedentedly long time to reach maximum brightness, and then slowly faded away.

For the sake of their study, the research team – which included members from the UK, Poland, Sweden, Northern Ireland, the Netherlands and Germany – studied a Type Ibn event known as OGLE-2014-SN-13. These types of explosions are thought to be the result of massive stars (which have lost their outer envelop of hydrogen) undergoing core-collapse, and whose ejecta interacts with a cloud of helium-rich circumstellar material (CSM).

The study was led by Emir Karamehmetoglu of The Oskar Klein Center at Stockholm University. As he told Universe Today via email:

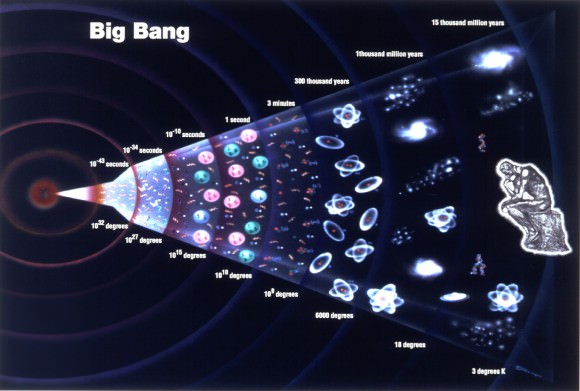

“Type Ibn supernovae are thought to be the explosions of very massive stars, surrounded by a dense region of extremely helium-rich material. We infer the existence of this Helium via the presence of narrow helium emission lines in their optical spectra. We also believe that there is very little, if any Hydrogen in the immediate surrounding of the star, because if it was there, it would show up much stronger than the Helium in the spectra. As you can imagine, this sort of configuration is very rare, since hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe by far.”

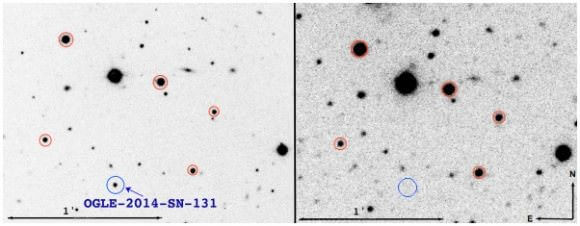

As already noted, Type Ibn supernova are characterized by a sudden and dramatic increase in their brightness, then a rapid decline. However, when observing OGLE-2014-SN-131 – which they detected on November 11th, 2014 using the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE) at the Warsaw University Astronomical Observatory – they witnessed something completely different.

“OGLE-2014-SN-131 was different because it took almost 50 days, as compared to the more typical ~1 week, for it to become bright,” said Karamehmetoglu. “Then it declined relatively slowly as well. The fact that it took several times longer than the typical rise to maximum brightness, which is unlike any other Ibn that has been studied before, makes it a very unique object.”

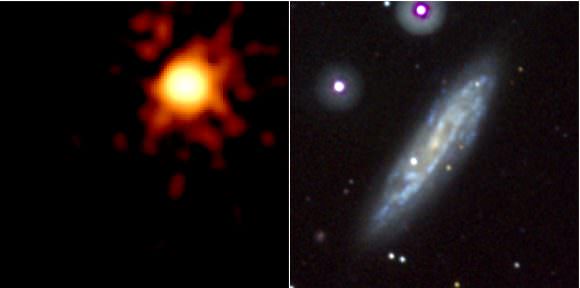

Thanks to data obtained by the OGLE-IV Transient Detection System, they were able to place OGLE-2014-SN-131 at a distance of about 372 ± 9 megaparsecs (1183.95 to 1242.66 million light years) from Earth. This was then followed-up with photometric observations using the OGLE telescope at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile and the Gamma-Ray Burst Optical/Near-Infrared Detector (GROND) at the La Silla Observatory.

The team also obtained spectroscopic data using the ESO’s New Technology Telescope (NTT) at La Silla and the Very Large Telescope (VLT) at the Paranal Observatory (both located in Chile). In addition to having an unusually long rise-time, the combined data also indicated that the supernova had an unusually broad light curve. To explain all this, the team considered a number of possibilities.

For starters, they considered standard radio-active decay models, which are known to power the lightcurves of most other Type I and Type II supernovae. However, these could not account for what they had observed with OGLE-2014-SN-131. As such, they began considering more exotic scenarios, which included energy being input from a young, rapidly spinning neutron star (aka. a magnetar) nearby.

While this model would explain the behavior of OGLE-2014-SN-131, it was limited in that it is not yet known what circumstances would be needed to invoke a magnetar. As such, Karamehmetoglu and his team also considered the possibility that the explosions might be powered by shocks created by the interaction of ejected material from the supernova with the helium-rich CSM.

Thanks to the spectral data obtained by the NTT and VLT, they knew that such material existed around the star, and the model was therefore able to reproduce the observed behavior. As Karamehmetoglu explained, it is for this reason that they favor this model over the others:

“In this scenario, the reason OGLE-2014-SN-131 is different from other Type Ibn SNe is due to the unusually massive nature of its progenitor star. A very massive star, between 40-60 times the mass of our Sun, located in a low-metallicity galaxy, probably gave rise to this SN by expelling a great amount of helium-rich matter, then eventually exploding as a SN.”

In addition to being a unique event, this study also some drastic implications for astronomy and the study of supernovae. Thanks to the detection of OGLE-2014-SN-131, any future models that attempt to explain how Type Ibn supernovae form now have a stringent constraint. At the same time, astronomers now have an existing model to consider if and when they witness other supernovae which exhibit particularly long rise times.

Looking ahead, this is precisely what Karamehmetoglu and his colleagues hope to do. “In our next effort, we will study other, less-rare, types of SN that have long rise times, and therefore are probably created by very massive stars,” he said. “We will get to take advantage of the comparison frame-work we developed when studying OGLE-2014-SN-131.”

Once more, the Universe has taught us that two of the more important aspects of scientific research are adaptability and a commitment to continuous discovery. When things don’t conform to existing models, develop new ones and test them out!

Further Reading: arXiv