[/caption]

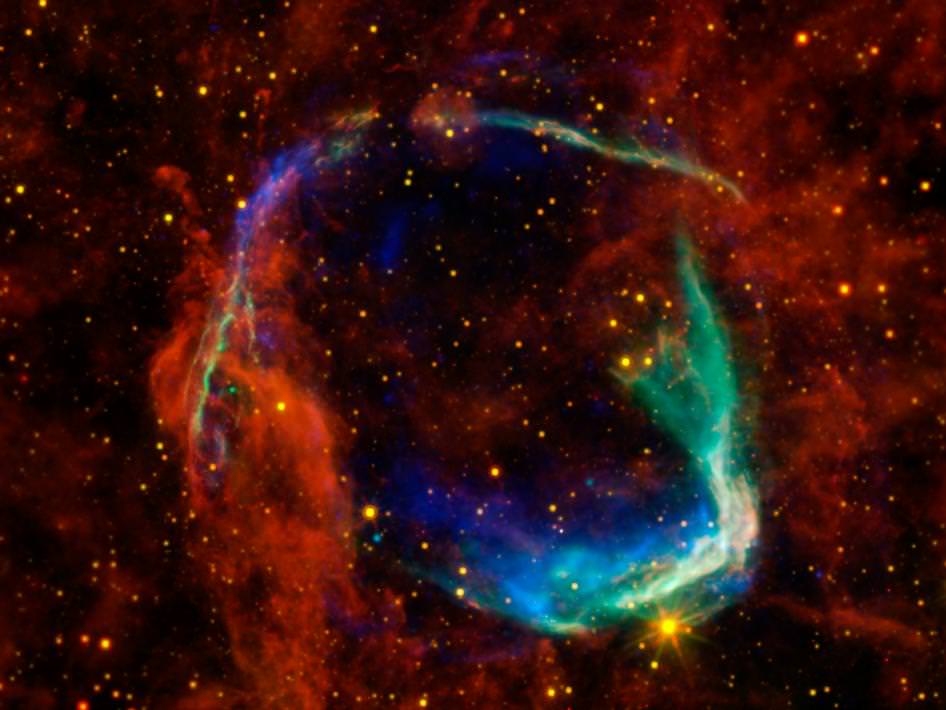

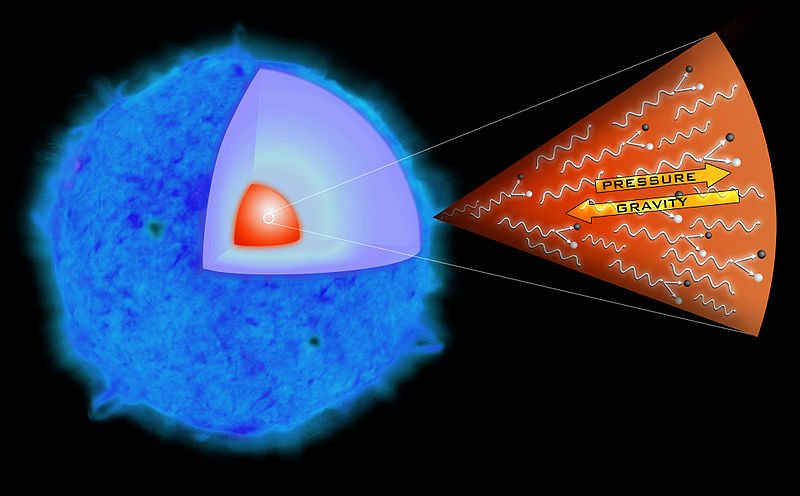

Astronomers have recognized various ways that stars can collapse to undergo a supernova. In one situation, an iron core collapses. The second involves a lower mass star with oxygen, neon, and magnesium in the core which suddenly captures electrons when the conditions are just right, removing them as a support mechanism and causing the star to collapse. While these two mechanisms make good physical sense, there has never been any observational support showing that both types occur. Until now that is. Astronomers led yb Christian Knigge and Malcolm Coe at the University of Southampton in the UK announced that they have detected two distinct sub populations in the neutron stars that result from these supernova.

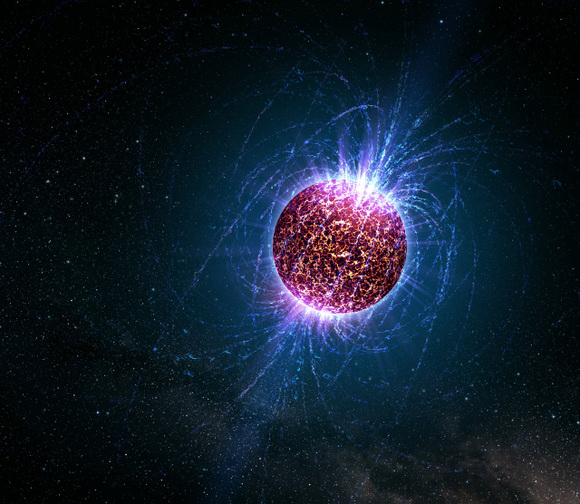

To make the discovery, the team studied a large number of a specific sub-class of neutron stars known as Be X-ray binaries (BeXs). These objects are a pair of stars formed by a hot B spectral class stars with hydrogen emission in their spectrum in a binary orbit with a neutron star. The neutron star orbits the more massive B star in an elliptical orbit, siphoning off material as it makes close approaches. As the accreted material strikes the neutron star’s surface it glows brightly in the X-rays, becoming, for a time, an X-ray pulsar allowing astronomers to measure the spin period of the neutron star.

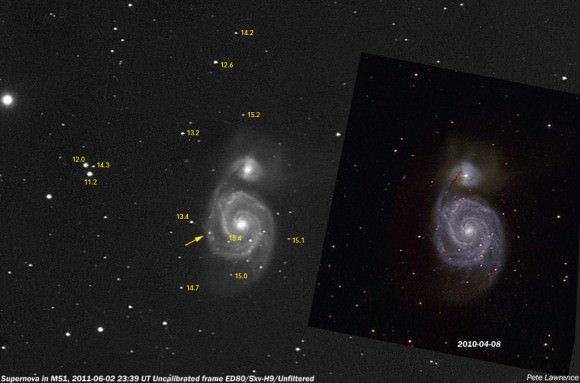

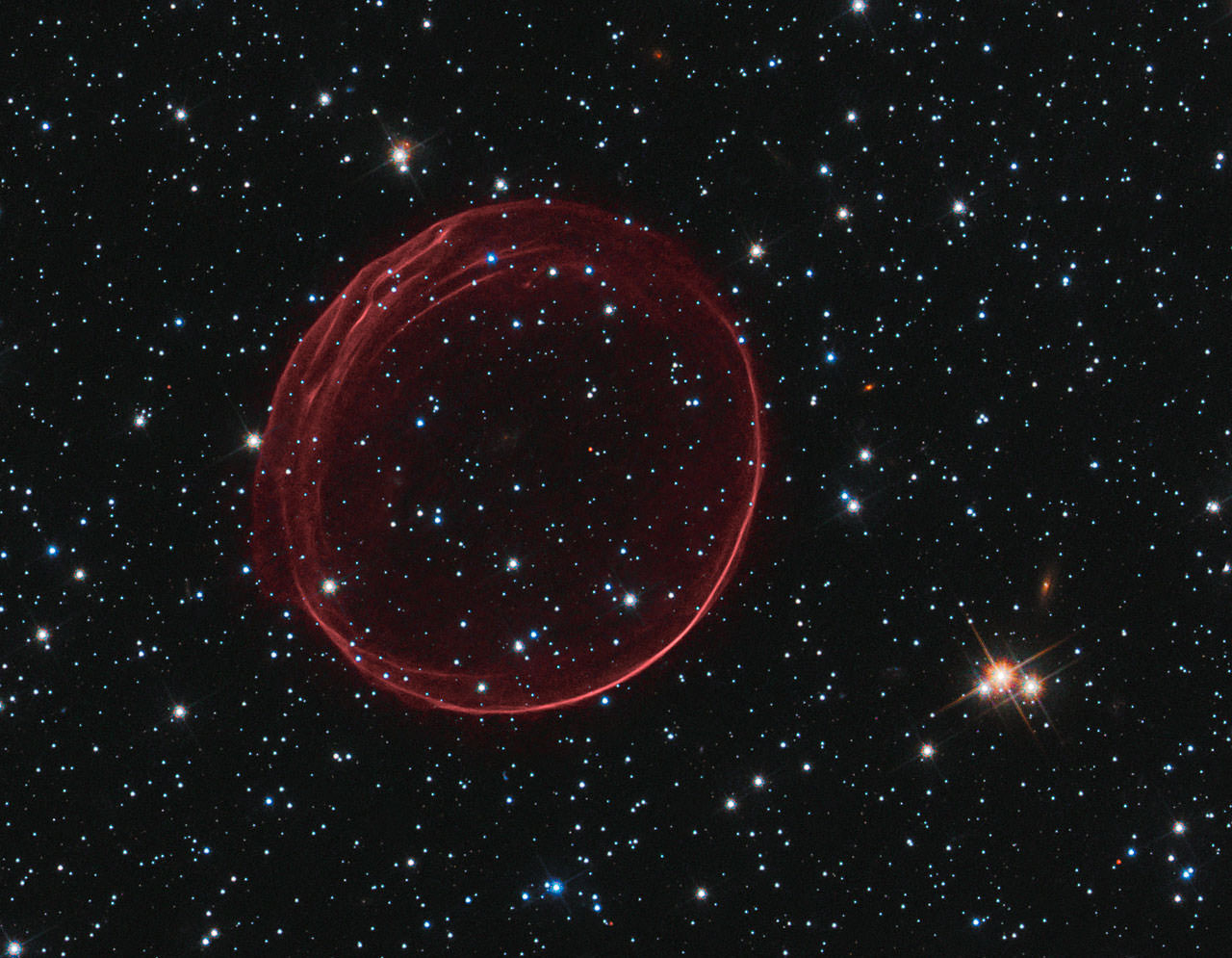

Such systems are common in the Small Magellanic Cloud which appears to have a burst of star forming activity about 60 million years ago, allowing for the massive B stars to be in the prime of their stellar lives. It is estimated that the Small Magellanic Cloud alone has as many BeXs as the entire Milky Way galaxy, despite being 100 times smaller. By studying these systems as well the Large Magellanic Cloud and Milky Way, the team found that there are two overlapping but distinct populations of BeX neutron stars. The first had a short period, averaging around 10 seconds. A second group had an average of around 5 minutes. The team surmises that the two populations are a result of the different supernova formation mechanisms.

The two different formation mechanisms should also lead to another difference. The explosion is expected to give the star a “kick” that can change the orbital characteristics. The electron-captured supernovae are expected to give a kick velocity of less than 50 km/sec whereas the iron core collapse supernovae should be over 200 km/sec. This would mean the iron core collapse stars should have preferentially longer and more eccentric orbits. The team attempted to discern whether this too was supported by their evidence, but only a small fraction of the stars they examined had determined eccentricities. Although there was a small difference, it is too early to determine whether or not it was due to chance.

According to Knigge, “These findings take us back to the most fundamental processes of stellar evolution and lead us to question how supernovae actually work. This opens up numerous new research areas, both on the observational and theoretical fronts.