A rogue star is one that has escaped the gravitational pull of its home galaxy. These stars drift through intergalactic space, and so are sometimes called intergalactic stars. Sometimes, when a rogue star is ejected from its galaxy, it drags its binary pair along for the ride.

Continue reading “Astronomers are Finding Binary Pairs of Stars Thrown out of Galaxies Together”Astronomers See the Exact Moment a Supernova Turned into a Black Hole (or Neutron Star)

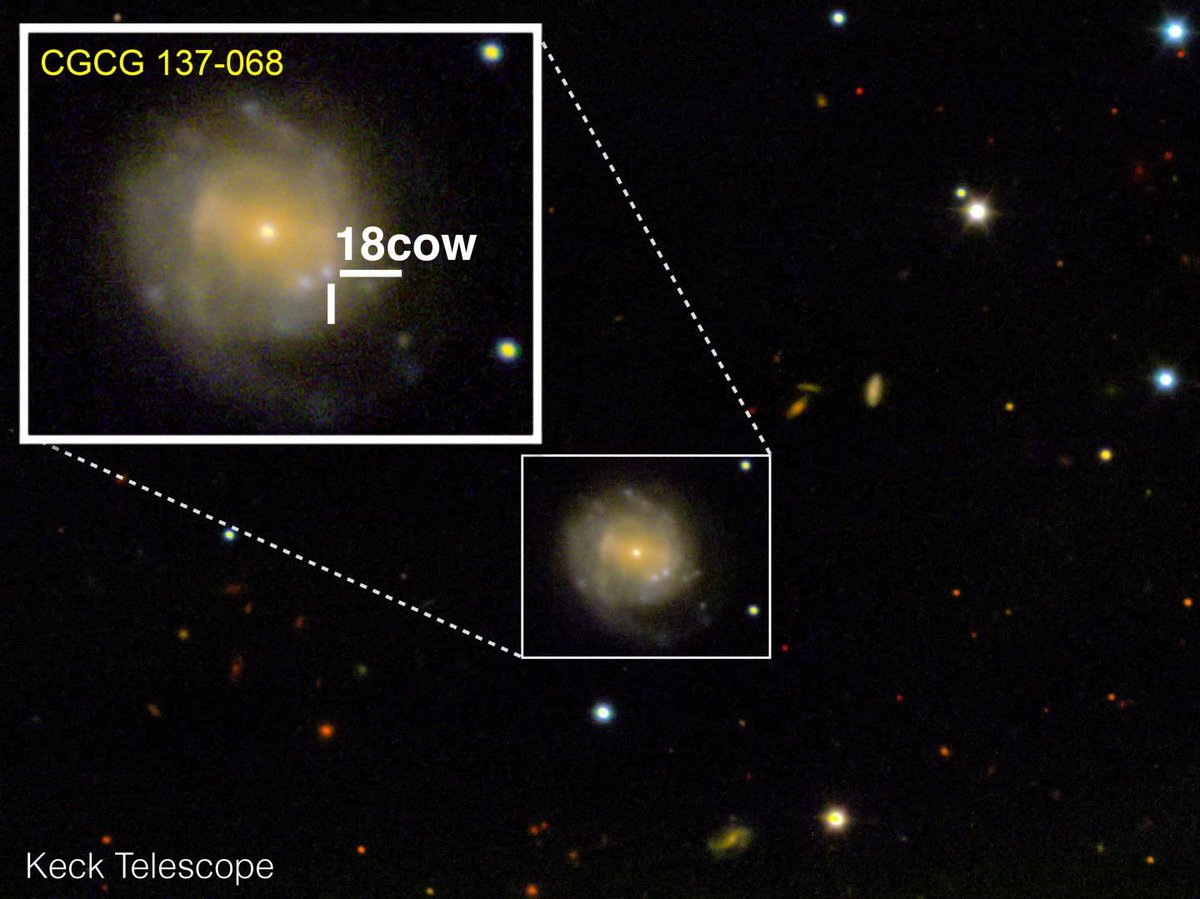

On June 17th 2018, the ATLAS (Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System) survey’s twin telescopes spotted something extraordinarily bright in the sky. The source was 200 million light years away in the constellation Hercules. The object was given the name AT2018cow or “The Cow.” The Cow flared up quickly, and then just as quickly it was gone.

What was it?

Continue reading “Astronomers See the Exact Moment a Supernova Turned into a Black Hole (or Neutron Star)”A Supernova 2.6 Million Years Ago Could Have Wiped Out the Ocean’s Large Animals

For many years, scientists have been studying how supernovae could affect life on Earth. Supernovae are extremely powerful events, and depending on how close they are to Earth, they could have consequences ranging from the cataclysmic to the inconsequential. But now, the scientists behind a new paper say they have specific evidence linking one or more supernova to an extinction event 2.6 million years ago.

About 2.6 million years ago, one or more supernovae exploded about 50 parsecs, or about 160 light years, away from Earth. At that same time, there was also an extinction event on Earth, called the Pliocene marine megafauna extinction. Up to a third of the large marine species on Earth were wiped out at the time, most of them living in shallow coastal waters.

“This time, it’s different. We have evidence of nearby events at a specific time.” – Dr. Adrian Melott, University of Kansas.

Continue reading “A Supernova 2.6 Million Years Ago Could Have Wiped Out the Ocean’s Large Animals”

Astronomers Finally Spot the Type of Star That Leads to Type 1C Supernovae

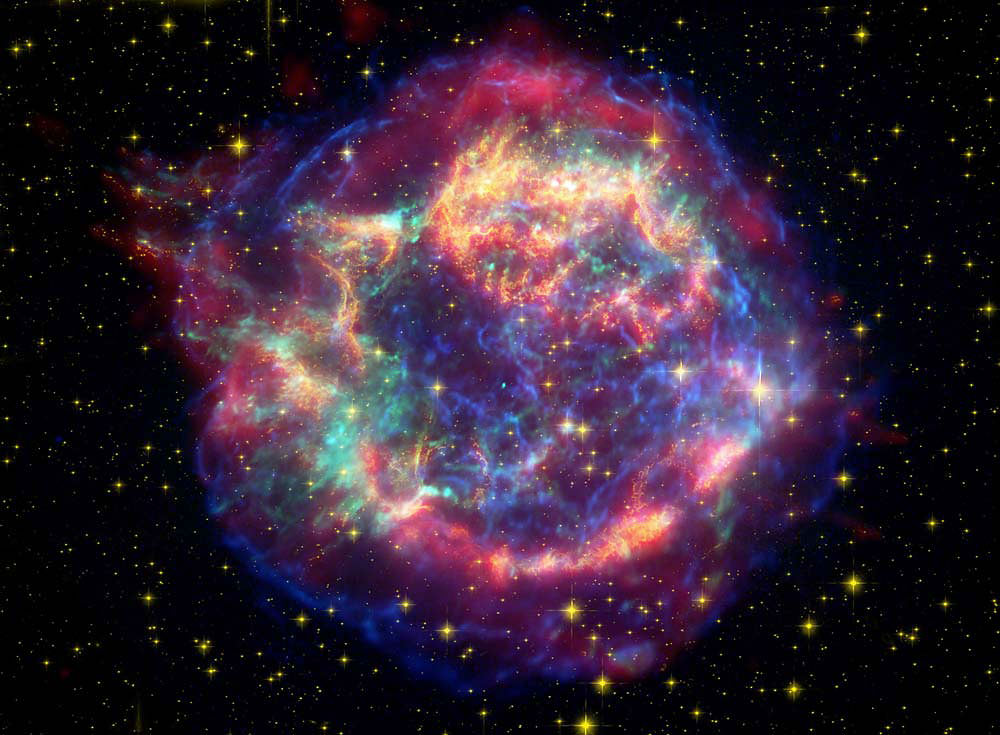

As astronomical phenomena go, supernovae are among the most fascinating and spectacular. This process occurs when certain types of stars reach the end of their lifespan, where they explode and throw off their outer layers. Thanks to generations of study, astronomers have been able to classify most observed supernovae into one of two categories (Type I and Type II) and determine which kinds of stars are the progenitors for each.

However, to date, astronomers have been unable to determine which type of star eventually leads to a Type Ic supernova – a special of class where a star undergoes core collapse after being stripped of its hydrogen and helium. But thanks to the efforts of two teams of astronomers that pored over archival data from the Hubble Space Telescope, scientists have now found the long sought-after star that causes this type of supernova.

Continue reading “Astronomers Finally Spot the Type of Star That Leads to Type 1C Supernovae”

Binary Stars Orbiting Each Other INSIDE a Planetary Nebula

Planetary nebulae are a fascinating astronomical phenomena, even if the name is a bit misleading. Rather than being associated with planets, these glowing shells of gas and dust are formed when stars enter the final phases of their lifespan and throw off their outer layers. In many cases, this process and the subsequent structure of the nebula is the result of the star interacting with a nearby companion star.

Recently, while examining the planetary nebula M3-1, an international team of astronomers noted something rather interesting. After observing the nebula’s central star, which is actually a binary system, they noticed that the pair had an incredibly short orbital period – i.e. the stars orbit each other once every 3 hours and 5 minutes. Based on this behavior, the pair are likely to merge and trigger a nova explosion.

Continue reading “Binary Stars Orbiting Each Other INSIDE a Planetary Nebula”

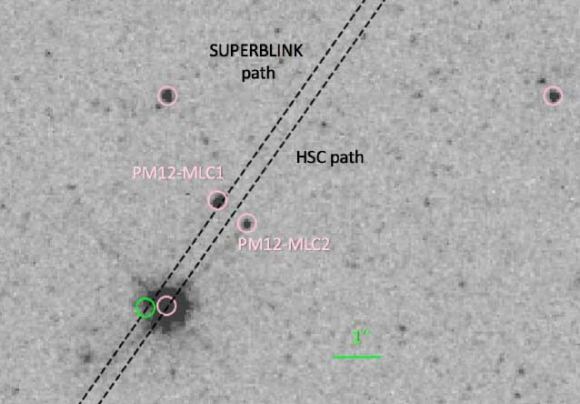

Astronomers Figure Out How to use Gravitational Lensing to Measure the Mass of White Dwarfs

For the sake of studying the most distant objects in the Universe, astronomers often rely on a technique known as Gravitational Lensing. Based on the principles of Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, this technique involves relying on a large distribution of matter (such as a galaxy cluster or star) to magnify the light coming from a distant object, thereby making it appear brighter and larger.

However, in recent years, astronomers have found other uses for this technique as well. For instance, a team of scientists from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) recently determined that Gravitational Lensing could also be used to determine the mass of white dwarf stars. This discovery could lead to a new era in astronomy where the mass of fainter objects can be determined.

The study which details their findings, titled “Predicting gravitational lensing by stellar remnants” appeared in the Monthly Noticed of the Royal Astronomical Society. The study was led by Alexander J. Harding of the CfA and included Rosanne Di Stefano, and Claire Baker (also from the CfA), as well as members from the University of Southampton, Georgia State University, the University of Nigeria, and Cornell University.

To put it simply, determining the mass of an astronomical object is one the greatest challenges for astronomers. Until now, the most successful method relied on binary systems because the orbital parameters of these systems depend on the masses of the two objects. Unfortunately, objects that are at the end states of stellar evolution – like black holes, neutron stars or white dwarfs – are often too faint or isolated to be detectable.

This is unfortunate, since these objects are responsible for a lot of dramatic astronomical events. These include the accretion of material, the emission of energetic radiation, gravitational waves, gamma-ray bursts, or supernovae. Many of these events are still a mystery to astronomers or the study of them is still in its infancy – i.e. gravitational waves. As they state in their study:

“Gravitational lensing provides an alternative approach to mass measurement. It has the advantage of only relying on the light from a background source, and can therefore be employed even for dark lenses. In fact, since light from the lens can interfere with the detection of lensing effects, compact objects are ideal lenses.”

As they go on to state, of the 18,000 lensing events that have been detected to date, roughly 10 to 15% are believed to have been caused by compact objects. However, scientists are unable to tell which of the detected events were due to compact lenses. For the sake of their study then, the team sought to circumvent this problem by identifying local compact objects and predicting when they might produce a lensing event so they could be studied.

“By focusing on pre-selected compact objects in the near vicinity of the Sun, we ensure that the lensing event will be caused by a white dwarf, neutron star, or black hole,” they state. “Furthermore, the distance and proper motion of the lens can be accurately measured prior to the event, or else afterwards. Armed with this information, the lensing light curve allows one to accurately measure the mass of the lens.”

In the end, the team determined that lensing events could be predicted from thousands of local objects. These include 250 neutron stars, 5 black holes, and roughly 35,000 white dwarfs. Neutron stars and black holes present a challenge since the known populations are too small and their proper motions and/or distances are not generally known.

But in the case of white dwarfs, the authors anticipate that they will provide for many lensing opportunities in the future. Based on the general motions of the white dwarfs across the sky, they obtained a statistical estimate that about 30-50 lensing events will take place per decade that could be spotted by the Hubble Space Telescope, the ESA’s Gaia mission, or NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). As they state in their conclusions:

“We find that the detection of lensing events due to white dwarfs can certainly be observed during the next decade by both Gaia and HST. Photometric events will occur, but to detect them will require observations of the positions of hundreds to thousands of far-flung white dwarfs. As we learn the positions, distances to, and proper motions of larger numbers of white dwarfs through the completion of surveys such as Gaia and through ongoing and new wide-field surveys, the situation will continue to improve.”

The future of astronomy does indeed seem bright. Between improvements in technology, methodology, and the deployment of next-generation space and ground-based telescopes, there is no shortage of opportunities to see and learn more.

Astronomers Find The Most Distant Supernova Ever: 10.5 Billion Light-Years Away

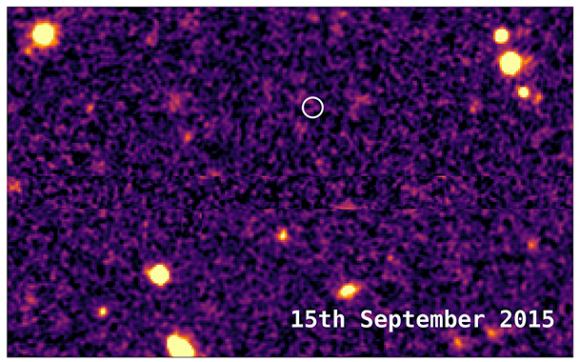

Astronomers have discovered the most distant supernova yet, at a distance of 10.5 billion light years from Earth. The supernova, named DES16C2nm, is a cataclysmic explosion that signaled the end of a massive star some 10.5 billion years ago. Only now is the light reaching us. The team of astronomers behind the discovery have published their results in a new paper available at arXiv.

“…sometimes you just have to go out and look up to find something amazing.” – Dr. Bob Nichol, University of Portsmouth.

The supernova was discovered by astronomers involved with the Dark Energy Survey (DES), a collaboration of astronomers in different countries. The DES’s job is to map several hundred million galaxies, to help us find out more about dark energy. Dark Energy is the mysterious force that we think is causing the accelerated expansion of the Universe.

DES16C2nm was first detected in August 2016. Its distance and extreme brightness were confirmed in October that year with three of our most powerful telescopes – the Very Large Telescope and the Magellan Telescope in Chile, and the Keck Observatory, in Hawaii.

DES16C2nm is what’s known as a superluminous supernova (SLSN), a type of supernova only discovered 10 years ago. SLSNs are the rarest—and the brightest—type of supernova that we know of. After the supernova exploded, it left behind a neutron star, which is the densest type of object in the universe. The extreme brightness of SLSNs, which can be 100 times brighter than other supernovae, are thought to be caused by material falling into the neutron star.

“It’s thrilling to be part of the survey that has discovered the oldest known supernova.” – Dr Mathew Smith, lead author, University of Southampton

Lead author of the study Dr Mathew Smith, of the University of Southampton, said: “It’s thrilling to be part of the survey that has discovered the oldest known supernova. DES16C2nm is extremely distant, extremely bright, and extremely rare – not the sort of thing you stumble across every day as an astronomer.”

Dr. Smith went on to say that not only is the discovery exciting just for being so distant, ancient, and rare. It’s also providing insights into the cause of SLSNs: “The ultraviolet light from SLSN informs us of the amount of metal produced in the explosion and the temperature of the explosion itself, both of which are key to understanding what causes and drives these cosmic explosions.”

“Now we know how to find these objects at even greater distances, we are actively looking for more of them as part of the Dark Energy Survey.” – Co-author Mark Sullivan, University of Southampton.

Now that the international team behind the Dark Energy Survey has found one of the SLSNs, they want to find more. Co-author Mark Sullivan, also of the University of Southampton, said: “Finding more distant events, to determine the variety and sheer number of these events, is the next step. Now we know how to find these objects at even greater distances, we are actively looking for more of them as part of the Dark Energy Survey.”

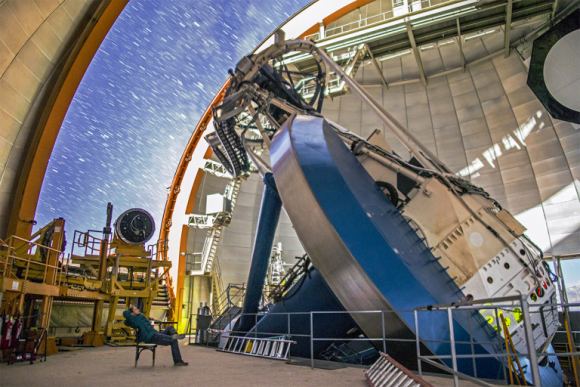

The instrument used by DES is the newly constructed Dark Energy Camera (DECam), which is mounted on the Victor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO) in the Chilean Andes. DECam is an extremely sensitive 570-megapixel digital camera designed and built just for the Dark Energy Survey.

The Dark Energy Survey involves more than 400 scientists from over 40 international institutions. It began in 2013, and will wrap up its five year mission sometime in 2018. The DES is using 525 nights of observation to carry out a deep, wide-area survey to record information from 300 million galaxies that are billions of light-years from Earth. DES is designed to help us answer a burning question.

According to Einstein’s General Relativity Theory, gravity should be causing the expansion of the universe to slow down. And we thought it was, until 1998 when astronomers studying distant supernovae found that the opposite is true. For some reason, the expansion is speeding up. There are really only two ways of explaining this. Either the theory of General Relativity needs to be replaced, or a large portion of the universe—about 70%—consists of something exotic that we’re calling Dark Energy. And this Dark Energy exerts a force opposite to the attractive force exerted by “normal” matter, causing the expansion of the universe to accelerate.

“…sometimes you just have to go out and look up to find something amazing.” – Dr. Bob Nichol, University of Portsmouth.

To help answer this question, the DES is imaging 5,000 square degrees of the southern sky in five optical filters to obtain detailed information about each of the 300 million galaxies. A small amount of the survey time is also used to observe smaller patches of sky once a week or so, to discover and study thousands of supernovae and other astrophysical transients. And this is how DES16C2nm was discovered.

Study co-author Bob Nichol, Professor of Astrophysics and Director of the Institute of Cosmology and Gravitation at the University of Portsmouth, commented: “Such supernovae were not thought of when we started DES over a decade ago. Such discoveries show the importance of empirical science; sometimes you just have to go out and look up to find something amazing.”

New Estimate Puts the Supernova Killzone Within 50 Light-Years of Earth

There are a lot of ways that life on Earth could come to an end: an asteroid strike, global climate catastrophe, or nuclear war are among them. But perhaps the most haunting would be death by supernova, because there’s absolutely nothing we could do about it. We’d be sitting ducks.

New research suggest that a supernova’s kill zone is bigger than we thought; about 25 light years bigger, to be exact.

Iron in the Ocean

In 2016, researchers confirmed that Earth has been hit with the effects from multiple supernovae. The presence of iron 60 in the seabed confirms it. Iron 60 is an isotope of iron produced in supernova explosions, and it was found in fossilized bacteria in sediments on the ocean floor. Those iron 60 remnants suggest that two supernovae exploded near our solar system, one between 6.5 to 8.7 million years ago, and another as recently as 2 million years ago.

Iron 60 is extremely rare here on Earth because it has a short half life of 2.6 million years. Any of the iron 60 created at the time of Earth’s formation would have decayed into something else by now. So when researchers found the iron 60 on the ocean floor, they reasoned that it must have another source, and that logical source is a supernova.

This evidence was the smoking gun for the idea that Earth has been struck by supernovae. But the questions it begs are, what effect did that supernova have on life on Earth? And how far away do we have to be from a supernova to be safe?

“…we can look for events in the history of the Earth that might be connected to them (supernova events).” – Dr. Adrian Melott, Astrophysicist, University of Kansas.

In a press release from the University of Kansas, astrophysicist Adrian Melott talked about recent research into supernovae and the effects they can have on Earth. “This research essentially proves that certain events happened in the not-too-distant past,” said Melott, a KU professor of physics and astronomy. “They make it clear approximately when they happened and how far away they were. Knowing that, we can consider what the effect may have been with definite numbers. Then we can look for events in the history of the Earth that might be connected to them.”

Earlier work suggested that a supernova kill zone is about 25-30 light years. If a supernova exploded that close to Earth, it would trigger a mass extinction. Bye-bye humanity. But new work suggests that 25 light years is an under-estimation, and that a supernova 50 light years away would be powerful enough to cause a mass extinction.

Supernovae: A Force Driving Evolution?

But extinction is just one effect a supernova could have on Earth. Supernovae can have other effects, and they might not all be negative. It’s possible that a supernovae about 2.6 million years ago even drove human evolution.

“Our local research group is working on figuring out what the effects were likely to have been,” Melott said. “We really don’t know. The events weren’t close enough to cause a big mass extinction or severe effects, but not so far away that we can ignore them either. We’re trying to decide if we should expect to have seen any effects on the ground on the Earth.”

Melott and his colleagues have written a new paper that focuses on the effects a supernova might have on Earth. In a new paper titled “A SUPERNOVA AT 50 PC: EFFECTS ON THE EARTH’S ATMOSPHERE AND BIOTA”, Melott and a team of researchers tried to shed light on Earth-supernova interactions.

The Local Bubble

There are a number of variables that come into play when trying to determine the effects of a supernova, and one of them is the idea of the Local Bubble. The Local Bubble itself is the result of one or more supernova explosion that occurred as long as 20 million years ago. The Local Bubble is a 300 light year diameter bubble of expanding gas in our arm of the Milky Way galaxy, where our Solar System currently resides. We’ve been travelling through it for the last five to ten million years. Inside this bubble, the magnetic field is weak and disordered.

Melott’s paper focused on the effects that a supernova about 2.6 million years ago would have on Earth in two instances: while both were within the Local Bubble, and while both were outside the Local Bubble.

The disrupted magnetic field inside the Local Bubble can in essence magnify the effects a supernova can have on Earth. It can increase the cosmic rays that reach Earth by a factor of a few hundred. This can increase the ionization in the Earth’s troposphere, which mean that life on Earth would be hit with more radiation.

Outside the Local Bubble, the magnetic field is more ordered, so the effect depends on the orientation of the magnetic field. The ordered magnetic field can either aim more radiation at Earth, or it could in a sense deflect it, much like our magnetosphere does now.

Focusing on the Pleistocene

Melott’s paper looks into the connection between the supernova and the global cooling that took place during the Pleistocene epoch about 2.6 million years ago. There was no mass extinction at that time, but there was an elevated extinction rate.

According to the paper, it’s possible that increased radiation from a supernova could have changed cloud formation, which would help explain a number of things that happened at the beginning of the Pleistocene. There was increased glaciation, increased species extinction, and Africa grew cooler and changed from predominantly forests to semi-arid grasslands.

Cancer and Mutation

As the paper concludes, it is difficult to know exactly what happened to Earth 2.6 million years ago when a supernova exploded in our vicinity. And it’s difficult to pinpoint an exact distance at which life on Earth would be in trouble.

But high levels of radiation from a supernova could increase the cancer rate, which could contribute to extinction. It could also increase the mutation rate, another contributor to extinction. At the highest levels modeled in this study, the radiation could even reach one kilometer deep into the ocean.

There is no real record of increased cancer in the fossil record, so this study is hampered in that sense. But overall, it’s a fascinating look at the possible interplay between cosmic events and how we and the rest of life on Earth evolved.

Sources:

- A supernova at 50 pc: Effects on the Earth’s atmosphere and biota

- Recent near-Earth supernovae probed by global deposition of interstellar radioactive 60Fe

- The locations of recent supernovae near the Sun from modelling 60Fe transport

- Proof that ancient supernovae zapped Earth sparks hunt for after effects

Chance Discovery Of A Three Hour Old Supernova

Supernovae are extremely energetic and dynamic events in the universe. The brightest one we’ve ever observed was discovered in 2015 and was as bright as 570 billion Suns. Their luminosity signifies their significance in the cosmos. They produce the heavy elements that make up people and planets, and their shockwaves trigger the formation of the next generation of stars.

There are about 3 supernovae every 100 hundred years in the Milky Way galaxy. Throughout human history, only a handful of supernovae have been observed. The earliest recorded supernova was observed by Chinese astronomers in 185 AD. The most famous supernova is probably SN 1054 (historic supernovae are named for the year they were observed) which created the Crab Nebula. Now, thanks to all of our telescopes and observatories, observing supernovae is fairly routine.

But one thing astronomers have never observed is the very early stages of a supernova. That changed in 2013 when, by chance, the automated Intermediate Palomar Transient Factory (IPTF) caught sight of a supernova only 3 hours old.

Spotting a supernovae in its first few hours is extremely important, because we can quickly point other ‘scopes at it and gather data about the SN’s progenitor star. In this case, according to a paper published at Nature Physics, follow-up observations revealed a surprise: SN 2013fs was surrounded by circumstellar material (CSM) that it ejected in the year prior to the supernova event. The CSM was ejected at a high rate of approximately 10 -³ solar masses per year. According to the paper, this kind of instability might be common among supernovae.

SN 2013fs was a red super-giant. Astronomers didn’t think that those types of stars ejected material prior to going supernova. But follow up observations with other telescopes showed the supernova explosion moving through a cloud of material previously ejected by a star. What this means for our understanding of supernovae isn’t clear yet, but it’s probably a game changer.

Catching the 3-hour-old SN 2013fs was an extremely lucky event. The IPTF is a fully-automated wide-field survey of the sky. It’s a system of 11 CCD’s installed on a telescope at the Palomar Observatory in California. It takes 60 second exposures at frequencies from 5 days apart to 90 seconds apart. This is what allowed it to capture SN 2013fs in its early stages.

Our understanding of supernovae is a mixture of theory and observed data. We know a lot about how they collapse, why they collapse, and what types of supernovae there are. But this is our first data point of a SN in its early hours.

SN 2013fs is 160 million light years away in a spiral-arm galaxy called NGC7610. It’s a type II supernova, meaning that it’s at least 8 times as massive as our Sun, but not more than 50 times as massive. Type II supernovae are mostly observed in the spiral arms of galaxies.

A supernova is the end state of some of the stars in the universe. But not all stars. Only massive stars can become supernova. Our own Sun is much too small.

Stars are like dynamic balancing acts between two forces: fusion and gravity.

As hydrogen is fused into helium in the center of a star, it causes enormous outward pressure in the form of photons. That is what lights and warms our planet. But stars are, of course, enormously massive. And all that mass is subject to gravity, which pulls the star’s mass inward. So the fusion and the gravity more or less balance each other out. This is called stellar equilibrium, which is the state our Sun is in, and will be in for several billion more years.

But stars don’t last forever, or rather, their hydrogen doesn’t. And once the hydrogen runs out, the star begins to change. In the case of a massive star, it begins to fuse heavier and heavier elements, until it fuses iron and nickel in its core. The fusion of iron and nickel is a natural fusion limit in a star, and once it reaches the iron and nickel fusion stage, fusion stops. We now have a star with an inert core of iron and nickel.

Now that fusion has stopped, stellar equilibrium is broken, and the enormous gravitational pressure of the star’s mass causes a collapse. This rapid collapse causes the core to heat again, which halts the collapse and causes a massive outwards shockwave. The shockwave hits the outer stellar material and blasts it out into space. Voila, a supernova.

The extremely high temperatures of the shockwave have one more important effect. It heats the stellar material outside the core, though very briefly, which allows the fusion of elements heavier than iron. This explains why the extremely heavy elements like uranium are much rarer than lighter elements. Only large enough stars that go supernova can forge the heaviest elements.

In a nutshell, that is a type II supernova, the same type found in 2013 when it was only 3 hours old. How the discovery of the CSM ejected by SN 2013fs will grow our understanding of supernovae is not fully understood.

Supernovae are fairly well-understood events, but their are still many questions surrounding them. Whether these new observations of the very earliest stages of a supernovae will answer some of our questions, or just create more unanswered questions, remains to be seen.

Weekly Space Hangout – January 27, 2017: Kimberly Cartier & Exoplanet WASP 103b

Host: Fraser Cain (@fcain)

Special Guest: Kimberly Cartier ( KimberlyCartier.org / @AstroKimCartier ) Continue reading “Weekly Space Hangout – January 27, 2017: Kimberly Cartier & Exoplanet WASP 103b”