Exploring asteroids and other small bodies throughout the solar system has gotten increasingly popular, as their small gravity wells make them ideal candidates for resource extraction, enabling the expansion of life into the solar system. However, the technical challenges facing a mission to explore one are fraught – since they’re so small and variable, understanding how to land on one is even more so. A team from the University of Trieste in Italy has proposed a mission idea that could help solve that problem by using an ability most humans have but never think about.

Continue reading “Covering an Asteroid With Balls Could Characterize Its Interior”Meet Steve, A Most Peculiar Aurora

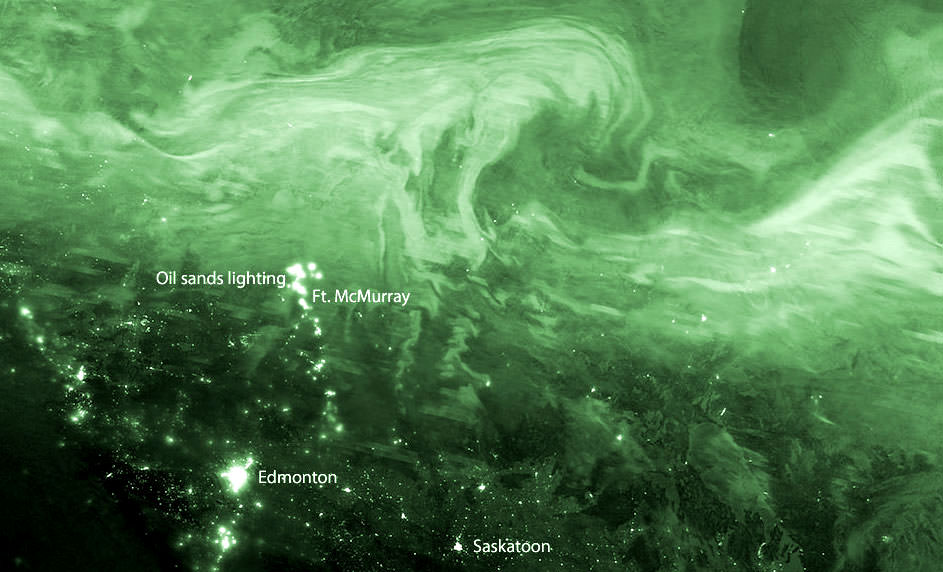

This remarkable image was captured last fall by Dave Markel, a photographer based in Kamloops, British Columbia. Later, aurora researcher Eric Donovan of the University of Calgary, discovered Markel’s strange ribbon of light while looking through photos of the northern lights on social media. Knowing he’d found something unusual, Donovan worked sifted through data from the European Space Agency’s Swarm magnetic field mission to try and understand the nature of the phenomenon.

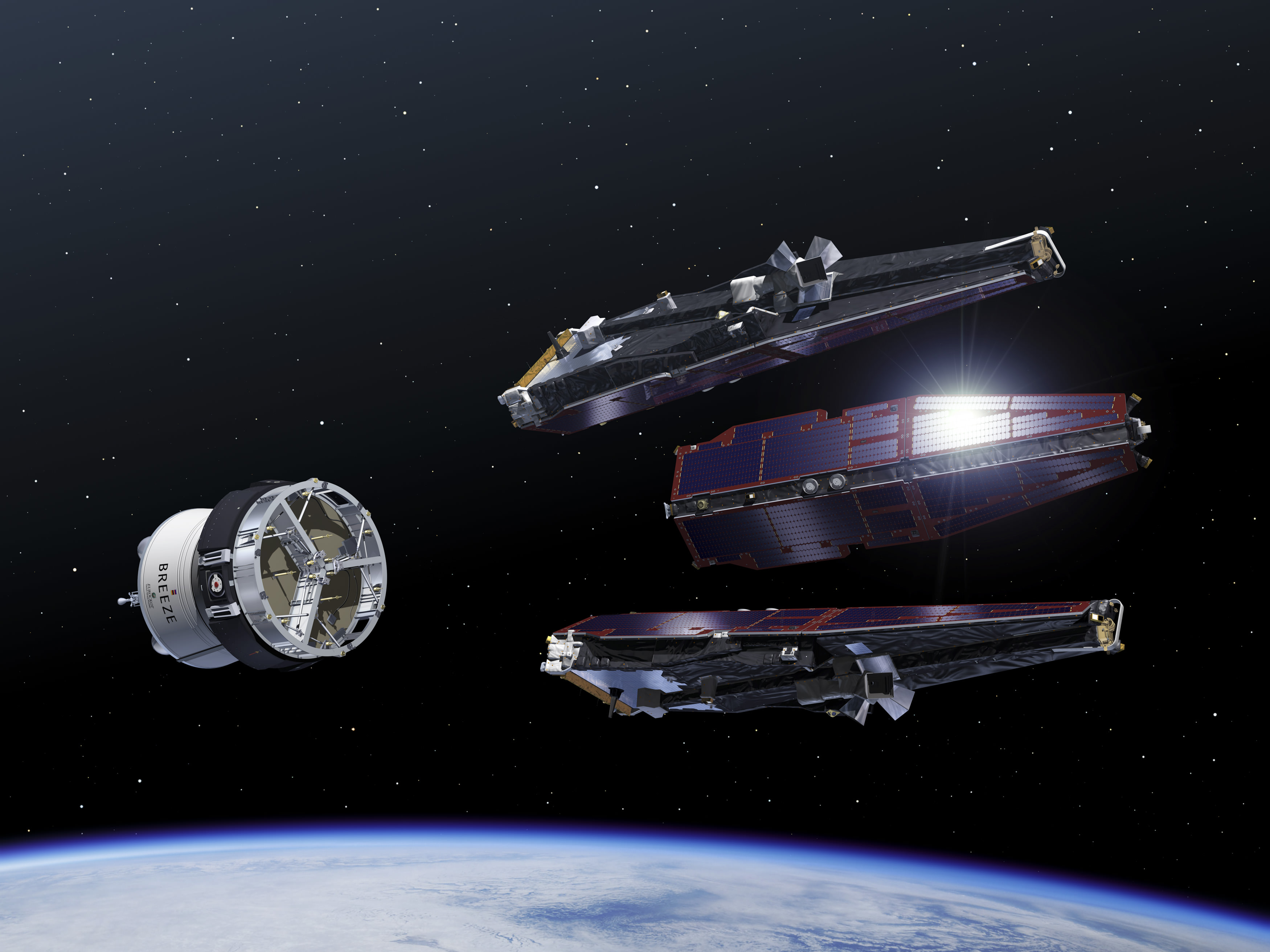

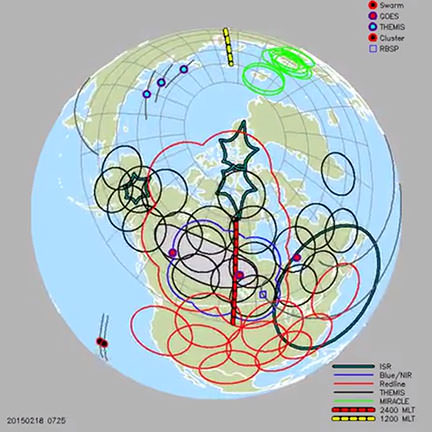

Launched on 22 November 2013, three identical Swarm satellites orbit the Earth measuring the magnetic fields that stem from Earth’s core, mantle, crust and oceans, as well as from the ionosphere and magnetosphere. Speaking at the recent Swarm science meeting in Canada, Donovan explained how this new finding couldn’t have happened 20 years ago when he started to study the aurora.

While the shimmering, eerie, light display of auroras might be beautiful and captivating, they’re also a visual reminder that Earth is connected electrically and magnetically to the Sun. The more we know about the aurora, the greater our understanding of that connection and how it affects everything from satellites to power grids to electrically-induced corrosion of oil pipelines.

“In 1997 we had just one all-sky imager in North America to observe the aurora borealis from the ground,” said Prof. Donovan. “Back then we would be lucky if we got one photograph a night of the aurora taken from the ground that coincides with an observation from a satellite. Now we have many more all-sky imagers and satellite missions like Swarm so we get more than 100 a night.”

And that’s where sharing photos and observations on social media can play an important role. Sites like the Great Lakes Aurora Hunters and Aurorasaurus serve as clearinghouses for observers to report auroral displays. Aurorasaurus connects citizen scientists to scientists and searches Twitter feeds for instances of the word ‘aurora,’ so skywatchers and scientists alike know the real-time extent of the auroral oval.

At a recent talk, Prof. Donovan met members the popular Facebook group Alberta Aurora Chasers. Looking at their photos, he came across the purple streak Markel and others had photographed which they’d been referring to as a “proton arc.” But such a feature, caused by hydrogen emission in the upper atmosphere, is too faint to be seen with the naked eye. Donovan knew it was something else, but what?Someone suggested “Steve.” Hey, why not?

While the group kept watch for the Steve’s return, Donovan and colleagues looked through data from the Swarm mission and his network of all-sky cameras. Before long he was able to match a ground sighting of streak to an overpass of one of the three Swarm satellites.

“As the satellite flew straight though Steve, data from the electric field instrument showed very clear changes,” said Donovan.

“The temperature 186 miles (300 km) above Earth’s surface jumped by 3000°C and the data revealed a 15.5-mile-wide (25 km) ribbon of gas flowing westwards at about 6 km/second compared to a speed of about 10 meters/second either side of the ribbon. A friend of mine compared it to a fluorescent light without the glass.

It turns out that these high-speed “rivers” of glowing auroral gas are much more common than we’d thought, and that in no small measure because of the efforts of an army of skywatchers and aurora photographers who keep watch for that telltale green glow in the northern sky.

I spoke to Steve’s keeper, Dave Markel, via e-mail yesterday and he described what the arc looked like to his eyes:

“It’s similar to the image just not as intense. It looks like a massive contrail moving rapidly across the sky. This one lasted almost an hour and ran in an arc almost perfectly east to west. I was directly below it but often there are green pickets (parallel streaks of aurora) rising above the streak.”

I know whereof Dave speaks because thanks to his photo and Prof. Donovan’s research, I realize I’ve seen and photographed Steve, too! In decades of aurora watching I’ve only seen this rare streak a handful of times. On most of those occasions, there was either no other aurora visible or minor activity in the northern sky. The narrow arc, which lasted for an hour or so, pulsed and flowed with light and occasionally, Markel’s “pickets” were visible. Back in May 1990 I had a camera on hand to get a picture.

Goes to show, you never know what you might see when you poke your head out for a look. Keep a lookout when aurora’s expected and maybe you’ll get to meet Steve, too.

‘Will We Soon Find Ourselves Back In The Stone Age?’ Why Swarm Is Watching Our Magnetic Field

A satellite triplet was born last week. The European Space Agency’s Swarm constellation flew into space on Friday (Nov. 22) on a quest to understand more about the Earth’s magnetic field.

Around the same time, ESA put out a few videos explaining why the magnetic field is important. This one explains that the magnetic field has weakened over the past few years, while the north pole has shifted direction. “In fact, a whole pole reversal is possible,” the narrator says. “It happened last 780,000 years ago at the very beginning of human history. But cavemen didn’t have mobile phone networks, GPS networks or power supplies.”

If a reversal did happen, it could affect those systems, the video adds, asking “Will we soon find ourselves back in the stone age?”

In the short term, however, the focus is on Swarm’s science. The satellites successfully unfurled their booms on Saturday (Nov. 23) and are now starting three months of commissioning before their planned four-year mission.

Once they get going, the satellites will make observations from two altitudes — a pair at about 285 miles (460 kilometers) in altitude and the final of the trio at a higher altitude of 330 miles (530 kilometers). They will monitor any changes in the Earth’s magnetic field, looking at spots ranging from the core of our planet to areas of the upper atmosphere.

Check out this ESA web page for more information about the mission.