When stars reach the end of their main sequence, they undergo a gravitational collapse, ejecting their outermost layers in a supernova explosion. What remains afterward is a dense, spinning core primarily made up of neutrons (aka. a neutron star), of which only 3000 are known to exist in the Milky Way Galaxy. An even rarer subset of neutron stars are magnetars, only two dozen of which are known in our galaxy.

These stars are especially mysterious, having extremely powerful magnetic fields that are almost powerful enough to rip them apart. And thanks to a new study by a team of international astronomers, it seems the mystery of these stars has only deepened further. Using data from a series of radio and x-ray observatories, the team observed a magnetar last year that had been dormant for about three years, and is now behaving somewhat differently.

The study, titled “Revival of the Magnetar PSR J1622–4950: Observations with MeerKAT, Parkes, XMM-Newton, Swift, Chandra, and NuSTAR“, recently appeared in The Astrophysical Journal. The team was led by Dr Fernando Camilo – the Chief Scientist at the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory (SARAO) – and included over 200 members from multiple universities and research institutions from around the world.

Magnetars are so-named because their magnetic fields are up to 1000 times stronger than those of ordinary pulsating neutron stars (aka. pulsars). The energy associated with these these fields is so powerful that it almost breaks the star apart, causing them to be unstable and display great variability in terms of their physical properties and electromagnetic emissions.

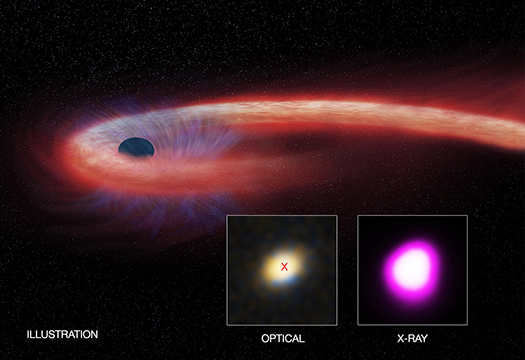

Whereas all magnetars are known to emit X-rays, only four have been known to emit radio waves. One of these is PSR J1622-4950 – a magnetar located about 30,000 light years from Earth. As of early 2015, this magnetar had been in a dormant state. But as the team indicated in their study, astronomers using the CSIRO Parkes Radio Telescope in Australia noted that it was becoming active again on April 26th, 2017.

At the time, the magnetar was emitting bright radio pulses every four seconds. A few days later, Parkes was shut down as part of a month-long planned maintenance routine. At about the same time, South Africa’s MeerKAT radio telescope began monitoring the star, despite the fact that it was still under construction and only 16 of its 64 radio dishes were available. Dr Fernando Camilo describes the discovery in a recent SKA South Africa press release:

“[T]he MeerKAT observations proved critical to make sense of the few X-ray photons we captured with NASA’s orbiting telescopes – for the first time X-ray pulses have been detected from this star, every 4 seconds. Put together, the observations reported today help us to develop a better picture of the behaviour of matter in unbelievably extreme physical conditions, completely unlike any that can be experienced on Earth”.

After the initial observations were made by the Parkes and MeerKAT observatories, follow-up observations were conducted using the XMM-Newton x-ray space observatory, Swift Gamma-Ray Burst Mission, the Chandra X-ray Observatory, and the Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR). With these combined observations, the team noted some very interesting things about this magnetar.

For one, they determined that PSR J1622-4950’s radio flux density, while variable, was approximately 100 times greater than it was during its dormant state. In addition, the x-ray flux was at least 800 times larger one month after reactivation, but began decaying exponentially over the course of a 92 to 130 day period. However, the radio observations noted something in the magnetar’s behavior that was quite unexpected.

While the overall geometry that was inferred from PSR J1622-4950’s radio emissions was consistent with what had been determined several years prior, their observations indicated that the radio emissions were now coming from a different location in the magnetosphere. This above all indicates how radio emissions from magnetars could differ from ordinary pulsars.

This discovery has also validated the MeerKAT Observatory as a world-class research instrument. This observatory is part of the Square Kilometer Array (SKA), the multi-radio telescope project that is building the world’s largest radio telescope in Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. For its part, MeerKAT uses 64 radio antennas to gather radio images of the Universe to help astronomers understand how galaxies have evolved over time.

Given the sheer volume of data collected by these telescopes, MeerKAT relies on both cutting edge-technology and a highly-qualified team of operators. As Abbott indicated, “we have a team of the brightest engineers and scientists in South Africa and the world working on the project, because the problems that we need to solve are extremely challenging, and attract the best”.

Prof Phil Diamond, the Director-General of the SKA Organization leading the development of the Square Kilometer Array, was also impressed by the contribution of the MeerKAT team. As he stated in an SKA press release:

“Well done to my colleagues in South Africa for this outstanding achievement. Building such telescopes is extremely difficult, and this publication shows that MeerKAT is becoming ready for business. As one of the SKA precursor telescopes, this bodes well for the SKA. MeerKAT will eventually be integrated into Phase 1 of SKA-mid telescope bringing the total dishes at our disposal to 197, creating the most powerful radio telescope on the planet”.

When the SKA goes online, it will be one of the most powerful ground-based telescopes in the world and roughly 50 times more sensitive than any other radio instrument. Along with other next-generation ground-based and space-telescopes, the things it will reveal about our Universe and how it evolved over time are expected to be truly groundbreaking.

Further Reading: SKA Africa, SKA, The Astrophysical Journal