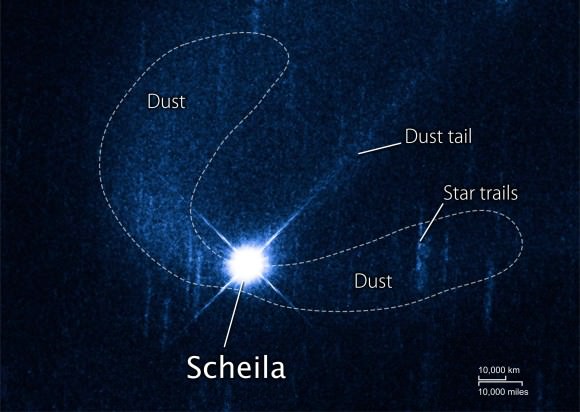

Asteroid or comet? That was the question astronomers were asking after an asteroid named Scheila had unexpectedly brightened, and seemingly sprouted a tail and coma. But follow-up observations by the Swift satellite and the Hubble Space Telescope show that these changes likely occurred after Scheila was struck by a much smaller asteroid.

“Collisions between asteroids create rock fragments, from fine dust to huge boulders, that impact planets and their moons,” said Dennis Bodewits, an astronomer at the University of Maryland in College Park and lead author of the Swift study. “Yet this is the first time we’ve been able to catch one just weeks after the smash-up, long before the evidence fades away.”

[/caption]

On Dec. 11, 2010, images from the University of Arizona’s Catalina Sky Survey, a project of NASA’s Near Earth Object Observations Program, revealed the Scheila to be twice as bright as expected and immersed in a faint comet-like glow. Looking through the survey’s archived images, astronomers inferred the outburst began between Nov. 11 and Dec. 3.

Three days after the outburst was announced, Swift’s Ultraviolet/Optical Telescope (UVOT) captured multiple images and a spectrum of the asteroid. Ultraviolet sunlight breaks up the gas molecules surrounding comets; water, for example, is transformed into hydroxyl (OH) and hydrogen (H). But none of the emissions most commonly identified in comets — such as hydroxyl or cyanogen (CN) — showed up in the UVOT spectrum. The absence of gas around Scheila led the Swift team to reject the idea that Scheila was actually a comet and that exposed ice accounted for the brightening.

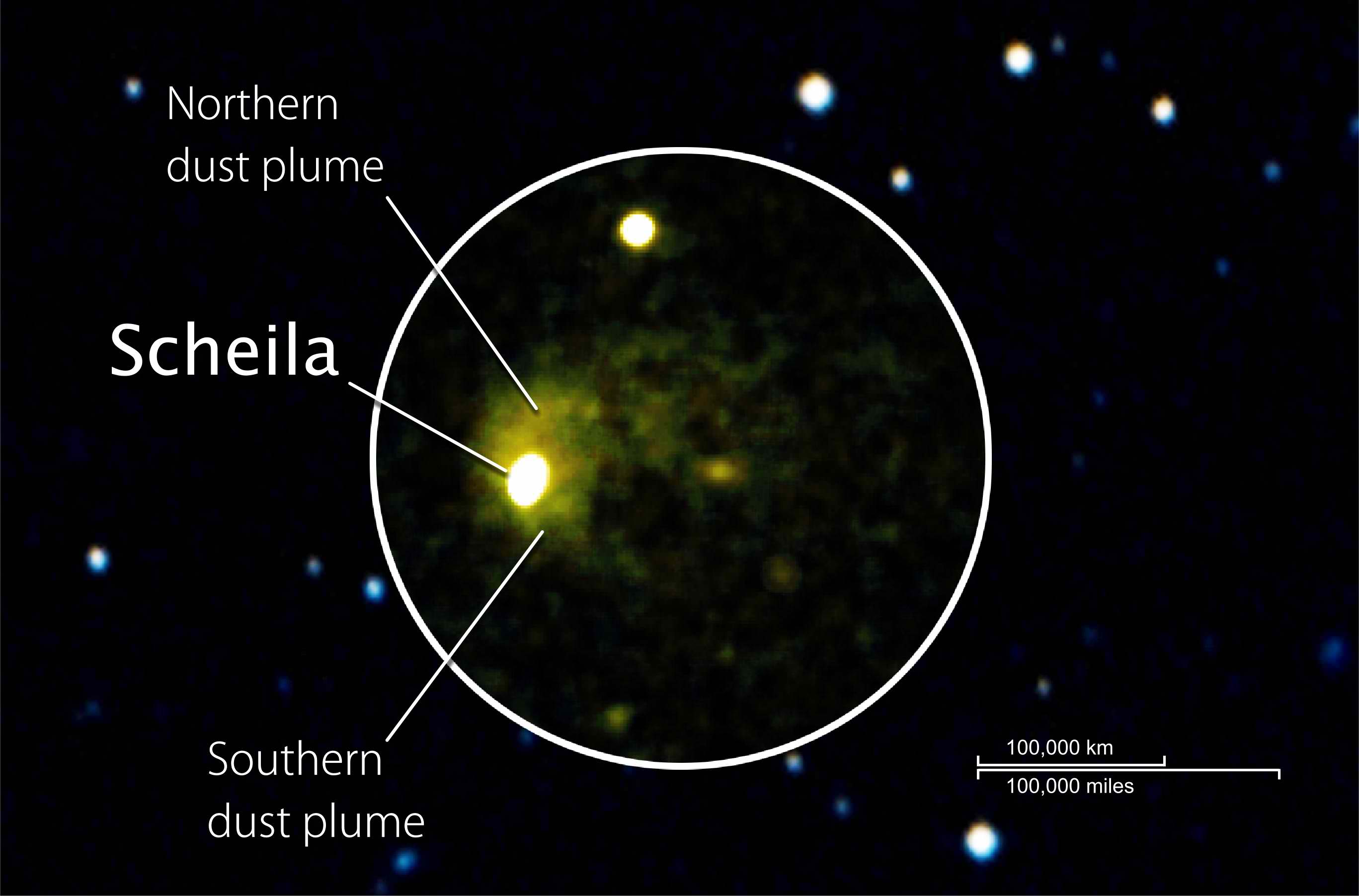

Hubble observed the asteroid’s fading dust cloud on Dec. 27, 2010, and Jan. 4, 2011. Images show the asteroid was flanked in the north by a bright dust plume and in the south by a fainter one. The dual plumes formed as small dust particles excavated by the impact were pushed away from the asteroid by sunlight.

The science teams from the two space observatories found the observations were best explained by a collision with a small asteroid impacting Scheila’s surface at an angle of less than 30 degrees, leaving a crater 1,000 feet across. Laboratory experiments show a more direct strike probably wouldn’t have produced two distinct dust plumes. The researchers estimated the crash ejected more than 660,000 tons of dust–equivalent to nearly twice the mass of the Empire State Building.

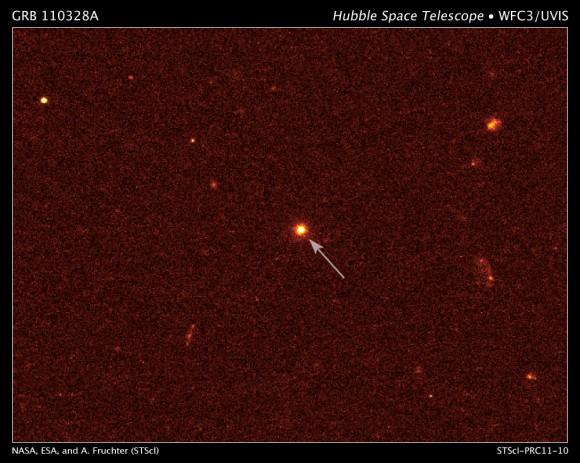

“The Hubble data are most simply explained by the impact, at 11,000 mph, of a previously unknown asteroid about 100 feet in diameter,” said Hubble team leader David Jewitt at the University of California in Los Angeles. Hubble did not see any discrete collision fragments, unlike its 2009 observations of P/2010 A2, the first identified asteroid collision.

Scheila is approximately 113 km (70 miles) across and orbits the sun every five years.

“The dust cloud around Scheila could be 10,000 times as massive as the one ejected from comet 9P/Tempel 1 during NASA’s UMD-led Deep Impact mission,” said co-author Michael Kelley, also at the University of Maryland. “Collisions allow us to peek inside comets and asteroids. Ejecta kicked up by Deep Impact contained lots of ice, and the absence of ice in Scheila’s interior shows that it’s entirely unlike comets.”

The studies will appear in the May 20 edition of The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Source: NASA Goddard