The Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) has accomplished some impressive things over the years. Between 2003 (when it was formed) and 2016, the agency has launched multiple satellites – ranging from x-ray and infrared astronomy to lunar and Venus atmosphere exploration probes – and overseen Japan’s participation in the International Space Station.

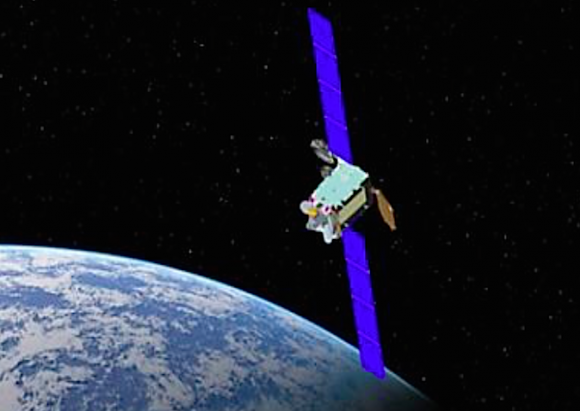

But in what is an historic mission – and a potentially controversial one – JAXA recently launched the first of three X-band defense communication satellites into orbit. By giving the Japanese Self-Defense Forces the ability to relay communications and commands to its armed forces, this satellite (known as DSN 2) represents an expansion of Japan’s military capability.

The launch took place on January 24th at 4:44 pm Japan Standard Time (JST) – or 0744 Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) – with the launch of a H-IIA rocket from Tanegashima Space Center. This was the thirty-second successful flight of the launch vehicle, and the mission was completed with the deployment of the satellite in Low-Earth Orbit – 35,000 km; 22,000 mi above the surface of the Earth.

Shortly after the completion of the mission, JAXA issued a press release stating the following:

“At 4:44 p.m., (Japan Standard Time, JST) January 24, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. and JAXA launched the H-IIA Launch Vehicle No. 32 with X-band defense communication satellite-2* on board. The launch and the separation of the satellite proceeded according to schedule. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. and JAXA express appreciation for the support in behalf of the successful launch. At the time of the launch the weather was fine, at 9 degrees Celsius, and the wind speed was 7.1 meters/second from the NW.”

This launch is part of a $1.1 billion program by the Japanese Defense Ministry to develop X-band satellite communications for the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF). With the overall goal of deploying three x-band relay satellites into geostationary orbit, its intended purpose is to reduce the reliance of Japan’s military (and those of its allies) on commercial and international communications providers.

While this may seem like a sound strategy, it is a potential source of controversy in that it may skirt the edge of what is constitutionally permitted in Japan. In short, deploying military satellites is something that may be in violation of Japan’s post-war agreements, which the nation committed to as part of its surrender to the Allies. This includes forbidding the use of military force as a means of solving international disputes.

It also included placing limitations on its Self-Defense Forces so they would not be capable of independent military action. As is stated in Article 9 of the Constitution of Japan (passed in 1947):

“(1) Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes.

(2) In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.”

However, since 2014, the Japanese government has sought to reinterpret Article 9 of the constitution, claiming that it allows the JSDF the freedom to defend other allies in case of war. This move has largely been in response to mounting tensions with North Korea over its development of nuclear weapons, as well as disputes with China over issues of sovereignty in the South China Sea.

This interpretation has been the official line of the Japanese Diet since 2015, as part of a series of measures that would allow the JSDF to provide material support to allies engaged in combat internationally. This justification, which claims that Japan and its allies would be endangered otherwise, has been endorsed by the United States. However, to some observers, it may very well be interpreted as an attempt by Japan to re-militarize.

In the coming weeks, the DSN 2 spacecraft will use its on-board engine to position itself in geostationary orbit, roughly 35,800 km (22,300 mi) above the equator. Once there, it will commence a final round of in-orbit testing before commencing its 15-year term of service.

Further Reading: Spaceflight Now