The picture of the Moon in the banner might not look all that spectacular, but it is absolutely astounding from a technical perspective. What makes it so unique is that it was taken via a telescope using a completely flat lens. This type of lens, called a metalens, has been around for a while, but a team of researchers from Pennsylvania State University (PSU) recently made the largest one ever. At eight cm in diameter, it was large enough to use in an actual telescope – and produce the above picture of the Moon, however, blurred it might be.

Continue reading “Researchers Build a Telescope with a Flat Lens”Lightweight, Flexible Lens Could be the Future of Space Telescopes

Holograms are useful for more than interesting-looking baubles in gift shops. Materials scientists have used them for applications from stress/strain gauges to data storage systems. It turns out they would also be useful in making extraordinarily lightweight, flexible mirrors for space telescopes. A new study led by researchers at the Rensselear Polytechnic Institue shows how that might happen.

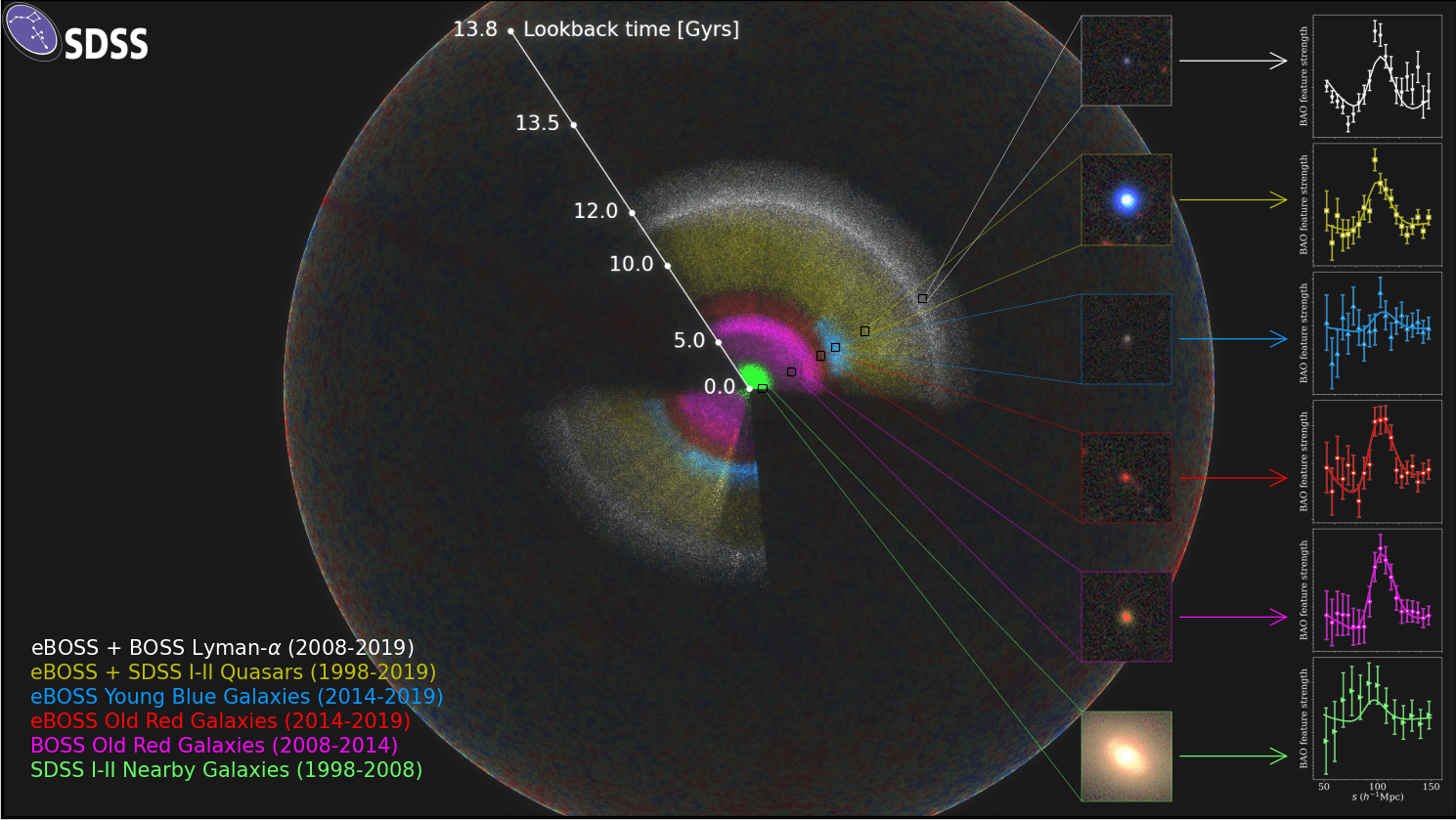

Continue reading “Lightweight, Flexible Lens Could be the Future of Space Telescopes”Take a Flight Through the Most Detailed 3D Map of the Universe Ever Made

Once I accidentally took a photo of one of the most important stars in the Universe…

That star highlighted in the photo is called M31_V1 and resides in the Andromeda Galaxy. The Andromeda – AKA M31- is the closest galaxy to our own Milky Way. But before it was known as a galaxy, it was called the Andromeda Nebula. Before this particular star in Andromeda was studied by Edwin Hubble, namesake of the Hubble Space Telescope, we didn’t actually know if other galaxies even existed. Think about that! As recently as a hundred years ago, we thought the Milky Way might be the ENTIRE Universe. Even then…that’s pretty big. The Milky Way is on the order of 150,000 light years across. A light year is about 10 TRILLION kilometers so even at the speed of light it would take nearly the same length of time to cross the Milky Way as humans have existed on planet Earth. M31_V1 changed all that.

Continue reading “Take a Flight Through the Most Detailed 3D Map of the Universe Ever Made”Messier 30 – The NGC 7099 Globular Cluster

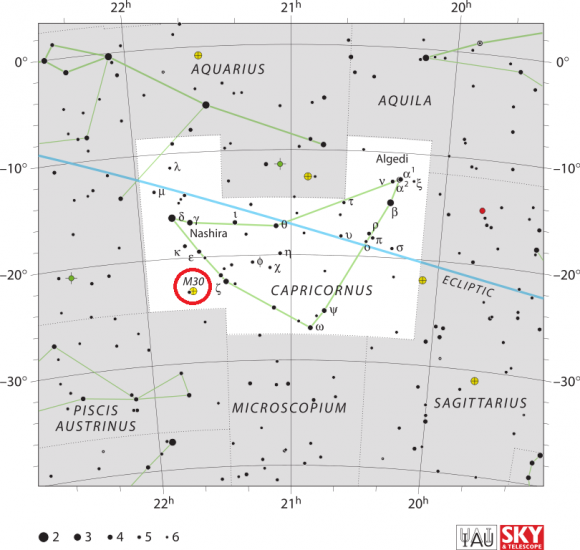

Welcome back to Messier Monday! In our ongoing tribute to the great Tammy Plotner, we take a look at the globular cluster known as Messier 30. Enjoy!

During the 18th century, famed French astronomer Charles Messier noted the presence of several “nebulous objects” in the night sky. Having originally mistaken them for comets, he began compiling a list of them so that others would not make the same mistake he did. In time, this list (known as the Messier Catalog) would come to include 100 of the most fabulous objects in the night sky.

One of these objects is Messier 30, a globular cluster located in the southern constellation of Capricornus. Owing to its retrograde orbit through the inner galactic halo, it is believed that this cluster was acquired from a satellite galaxy in the past. Though it is invisible to the naked eye, this cluster can be viewed using little more than binoculars, and is most visible during the summer months.

Description:

Messier measures about 93 light years across and lies at a distance of about 26,000 light years from Earth, and approaching us at a speed of about 182 kilometers per second. While it looks harmless enough, its tidal influence covers an enormous 139 light years – far greater than its apparent size.

Half of its mass is so concentrated that literally thousands of stars could be compressed in an area that spans no further than the distance between our solar system and Sirius! However, inside this density only 12 variable stars have been found and very little evidence of any stellar collisions, although a dwarf nova has been recorded!

So what’s so special about this little globular? Try a collapsed core – and one that’s even been resolved by Earth-bound telescopes. According to Bruce Jones Sams III, an astrophysicists at Harvard University:

“The globular cluster NGC 7099 is a prototypical collapsed core cluster. Through a series of instrumental, observational, and theoretical observations, I have resolved its core structure using a ground based telescope. The core has a radius of 2.15 arcsec when imaged with a V band spatial resolution of 0.35 arcsec. Initial attempts at speckle imaging produced images of inadequate signal to noise and resolution. To explain these results, a new, fully general signal-to-noise model has been developed. It properly accounts for all sources of noise in a speckle observation, including aliasing of high spatial frequencies by inadequate sampling of the image plane. The model, called Full Speckle Noise (FSN), can be used to predict the outcome of any speckle imaging experiment. A new high resolution imaging technique called ACT (Atmospheric Correlation with a Template) was developed to create sharper astronomical images. ACT compensates for image motion due to atmospheric turbulence.”

Photography is an important tool for astronomers to work with – both land and space-based. By combining results, we can learn far more than just from the results of one telescope observation alone. As Justin H. Howell wrote in a 1999 study:

“It has long been known that the post-core-collapse globular cluster M30 (NGC 7099) has a bluer-inward color gradient, and recent work suggests that the central deficiency of bright red giant stars does not fully account for this gradient. This study uses Hubble Space Telescope Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 images in the F439W and F555W bands, along with ground-based CCD images with a wider field of view for normalization of the noncluster background contribution. The quoted uncertainty accounts for Poisson fluctuations in the small number of bright evolved stars that dominate the cluster light. We explore various algorithms for artificially redistributing the light of bright red giants and horizontal-branch stars uniformly across the cluster. The traditional method of redistribution in proportion to the cluster brightness profile is shown to be inaccurate. There is no significant residual color gradient in M30 after proper uniform redistribution of all bright evolved stars; thus, the color gradient in M30’s central region appears to be caused entirely by post-main-sequence stars.”

So what happens when you dig even deeper with a different type of photography? Just ask the folks from Chandra – like Phyllis M. Lugger, who wrote in her study, “Chandra X-ray Sources in the Collapsed-Core Globular Cluster M30 (NGC 7099)“:

“We report the detection of six discrete, low-luminosity X-ray sources, located within 12” of the center of the collapsed-core globular cluster M30 (NGC 7099), and a total of 13 sources within the half-mass radius, from a 50 ks Chandra ACIS-S exposure. Three sources lie within the very small upper limit of 1.9” on the core radius. The brightest of the three core sources has a blackbody-like soft X-ray spectrum, which is consistent with it being a quiescent low-mass X-ray binary (qLMXB). We have identified optical counterparts to four of the six central sources and a number of the outlying sources, using deep Hubble Space Telescope and ground-based imaging. While the two proposed counterparts that lie within the core may represent chance superpositions, the two identified central sources that lie outside of the core have X-ray and optical properties consistent with being cataclysmic variables (CVs). Two additional sources outside of the core have possible active binary counterparts.”

History of Observation:

When Charles Messier first encountered this globular cluster in 1764, he was unable to resolve individual stars, and mistakenly believed it to be a nebula. As he wrote in his notes at the time:

“In the night of August 3 to 4, 1764, I have discovered a nebula below the great tail of Capricornus, and very near the star of sixth magnitude, the 41st of that constellation, according to Flamsteed: one sees that nebula with difficulty in an ordinary [non-achromatic] refractor of 3 feet; it is round, and I have not seen any star: having examined it with a good Gregorian telescope which magnifies 104 times, it could have a diameter of 2 minutes of arc. I have compared the center with the star Zeta Capricorni, and I have determined its position in right ascension as 321d 46′ 18″, and its declination as 24d 19′ 4″ south. This nebula is marked in the chart of the famous Comet of Halley which I observed at its return in 1759.”

However, we cannot fault Messier, for his job was to hunt comets and we thank him for logging this object for further study. Perhaps the first clue to M30’s underlying potential came from Sir William Herschel, who often studied Messier’s objects, but did not report his findings formally. In his personal notes he wrote:

“A brilliant cluster, the stars of which are gradually more compressed in the middle. It is insulated, that is, none of the stars in the neighborhood are likely to be connected with it. Its diameter is from 2’40” to 3’30”. The figure is irregularly round. The stars about the centre are so much compressed as to appear to run together. Towards the north, are two rows of bright stars 4 or 5 in a line. In this accumulation of stars, we plainly see the exertion of a central clustering power, which may reside in a central mass, or, what is more probable, in the compound energy of the stars about the centre. The lines of bright stars, although by a drawing made at the time of observation, one of them seems to pass through the cluster, are probably not connected with it.”

So, as telescopes progressed and resolution improved, so did our way of thinking about what we were seeing… By Admiral Smyth’s time, things had improved even more and so had the art of understanding more:

“A fine pale white cluster, under the creature’s caudal fin, and about 20 deg west-north-west of Fomalhaut, where it precedes 41 Capricorni, a star of 5th magnitude, within a degree. This object is bright, and from the straggling streams of stars on its northern verge, has an elliptical aspect, with a central blaze; and there are but few other stars, or outliers, in the field.

“When Messier discovered this, in 1764, he remarked that it was easily seen with a 3 1/2-foot telescope, that it was a nebula, unaccompanied by any star, and that its form was circular. But in 1783 it was attacked by WH [William Herschel] with both his 20-foot Newtonians, and forthwith resolved into a brilliant cluster, with two rows pf stars, four or five in a line, which probably belong to it; and therefore he deemed it insulated. Independently of this opinion, it is situated in a blankish space, one of those chasmata which Lalande termed d’espaces vuides, wherein he could not perceive a star of the 9th magnitude in the achromatic telescope of sixty-seven millimetres aperture. By a modification of his very ingenious gauging process, Sir William considered the profundity of this cluster to be of the 344th order.

“Here are materials for thinking! What an immensity of space is indicated! Can such an arrangement be intended, as a bungling spouter of the hour insists, for a mere appendage to the speck of a world on which we dwell, to soften the darkness of its petty midnight? This is impeaching the intelligence of Infinite Wisdom and Power, in adapting such grand means to so disproportionate an end. No imagination can fill up the picture of which the visual organs afford the dim outline; and he who confidently probes the Eternal Design cannot be many removes from lunacy. It was such a consideration that made the inspired writer claim, “How unsearchable are His operations, and His ways past finding out!”

Throughout all historic observing notes, you’ll find notations like “remarkable” and even Dreyer’s famous exclamation points. Even though M30 may not be the easiest to find, nor the brightest of the Messier objects, it is still quite worthy of your time and attention!

Locating Messier 30:

Finding M30 is not an easy task, unless you’re using a GoTo telescope. In any other case, it’s a starhop process, which must begin with identifying the the big grin-shape of the constellation of Capricornus. Once you’ve separated out this constellation, you’ll begin to notice that many of its primary asterism stars are paired – which is a good thing! The northeastern most pair are Gamma and Delta, which is where binocular-users should start.

As you move slowly south and slightly west, you’ll encounter your next wide pair – Chi and Epsilon. The next southwestern set is 36 Cap and Zeta. Now, from here you have two options! You can find Messier 30 a little more than a finger width east(ish) of Zeta (about half a binocular field)… or, you can return to Epsilon and look about one binocular field south (about 3 degrees) for star 41 which will appear just east of Messier 30 in the same field of view.

For the finderscope, star 41 is a critical giveaway to the globular cluster’s position! It won’t be visible to the unaided eye, but even a little magnification will reveal its presence. Using binoculars or a very small telescope, Messier 30 will appear as only a small, faded gray ball of light with a small star beside it. However, with telescope apertures as small as 4″ you’ll begin some resolution on this overlooked globular cluster and larger apertures will resolve it nicely.

And here are the quick facts on Messier 30 to help you get started:

Object Name: Messier 30

Alternative Designations: M30, NGC 7099

Object Type: Class V Globular Cluster

Constellation: Capricornus

Right Ascension: 21 : 40.4 (h:m)

Declination: -23 : 11 (deg:m

Distance: 26.1 (kly)

Visual Brightness: 7.2 (mag)

Apparent Dimension: 12.0 (arc min)

We have written many interesting articles about Messier Objects here at Universe Today. Here’s Tammy Plotner’s Introduction to the Messier Objects, , M1 – The Crab Nebula, M8 – The Lagoon Nebula, and David Dickison’s articles on the 2013 and 2014 Messier Marathons.

Be to sure to check out our complete Messier Catalog. And for more information, check out the SEDS Messier Database.

Sources:

What If We Do Find Aliens?

Time to talk about my favorite topic: aliens.

We’ve covered the Fermi Paradox many times over several articles on Universe Today. This is the idea that the Universe is huge, and old, and the ingredients of life are everywhere. Life could and should have have appeared many times across the galaxy, but it’s really strange that we haven’t found any evidence for them yet.

Continue reading “What If We Do Find Aliens?”New Lenses To Help In The Hunt For Dark Energy

Since the 1990s, scientists have been aware that for the past several billion years, the Universe has been expanding at an accelerated rate. They have further hypothesized that some form of invisible energy must be responsible for this, one which makes up 68.3% of the mass-energy of the observable Universe. While there is no direct evidence that this “Dark Energy” exists, plenty of indirect evidence has been obtained by observing the large-scale mass density of the Universe and the rate at which is expanding.

But in the coming years, scientists hope to develop technologies and methods that will allow them to see exactly how Dark Energy has influenced the development of the Universe. One such effort comes from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, where scientists are working to develop an instrument that will create a comprehensive 3D map of a third of the Universe so that its growth history can be tracked.

Continue reading “New Lenses To Help In The Hunt For Dark Energy”

Weekly Space Hangout – June 5, 2015: Stephen Fowler, Creative Director at InfoAge

Host: Fraser Cain (@fcain)

Special Guest: This week we welcome Stephen Fowler, who is the Creative Director at InfoAge, the organization behind refurbishing the TIROS 1 dish and the Science History Learning Center and Museum at Camp Evans, Wall, NJ.

Guests:

Jolene Creighton (@jolene723 / fromquarkstoquasars.com)

Morgan Rehnberg (cosmicchatter.org / @MorganRehnberg )

Continue reading “Weekly Space Hangout – June 5, 2015: Stephen Fowler, Creative Director at InfoAge”

Astronomy Cast Ep. 367: Spitzer does Exoplanets

We’ve spent the last few weeks talking about different ways astronomers are searching for exoplanets. But now we reach the most exciting part of this story: actually imaging these planets directly. Today we’re going to talk about the work NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope has done viewing the atmospheres of distant planets.

Continue reading “Astronomy Cast Ep. 367: Spitzer does Exoplanets”

Are Aliens Watching Old TV Shows?

You’ve probably heard the trope about how aliens have been watching old episodes of “I Love Lucy” and might think these are our “historical documents”. How far have our signals reached?

Television transmissions expand outward from the Earth at the speed of light, and there’s a trope in science fiction that aliens have learned everything about humans by watching our television shows. If you’re 4 light-years away, you’re see the light from the Earth as it looked 4 years ago, and some of that light includes television transmissions, as radio waves are just another form of electromagnetism – it’s all just light.

Humans began serious television service in the 1930s, and by the modern era, there were thousands of powerful transmitters pumping out electromagnetic radiation for all to see. So are aliens watching “I Love Lucy” or footage from World War II and believing it all to be part of our “Historical Documents”?

The first radio broadcasts started in the early 1900s. At the time I’m recording this video, it’s late 2014, so those transmissions have escaped into space 114 years ago. This means our transmissions have reached a sphere of stars with a radius of 114 light-years.

Are there other stars in that volume of space? Absolutely. It’s estimated that there are more than 14,000 stars within 100 light years of Earth. Most of those are tiny red dwarf stars, but there would be hundreds of sunlike stars.

As we’re discovering, almost all of those stars will have planets, many of which will be Earthlike. It’s almost certain some of those stars will have planets in the habitable zone, and could have evolved life forms, technology and television sets and were able to learn of the Stealth Haze and the Mak’Tar chant of strength.

Will the signals be powerful enough to stretch across the vast distances of space and reach another world so that many generations of aliens can hang their hopes that James Tiberius Kirk never visits their planet with his loose morals, questionably applied prime directive, irresistible charms and pants aflame with who knows what kinds of interstellar STIs?

Here’s the problem. Broadcast towers transmit their signals outward in a sphere, which falls under the inverse square law. The strength of the signal decreases massively over distance. By the time you’ve gone a few light years, the signal is almost non-existent.

Aliens could build a huge receiver, like the square kilometer array being built right now, but the signals they could receive from Earth would be a billion billion billion times weaker. Very hard to pick out from the background radiation. And by Grabthar’s hammer, I assure you it’s only by focusing our transmissions and beaming them straight at another star do we stand a chance of alerting aliens of our presence. Which, like it or not, is something we’ve done. So there’s that.

We’ve really been broadcasting our existence for hundreds of millions of years. The very presence of oxygen in the atmosphere of the Earth would tell any alien with a good enough telescope that there’s life here. Aliens could tell when we invented fire, when we developed steam technology, and what kinds of cars we like to drive, just by looking at our atmosphere. So don’t worry about our transmissions, the jig is up.

What do you think? Is it a good idea to alert aliens to our presence? Should we get rid of all that oxygen in our atmosphere and keep a low profile?

How Do We Know How Old Everything Is?

We hear that rocks are a certain age, and stars are another age. And the Universe itself is 13.7 billion years old. But how do astronomers figure this out?

I know it’s impolite to ask, but, how old are you? And how do you know? And doesn’t comparing your drivers license to your beautiful and informative “Year In Space” calendar feel somewhat arbitrary? How do we know old how everything is when what we observe was around long before calendars, or the Earth, or even the stars?

Scientists have pondered about the age of things since the beginning of science. When did that rock formation appear? When did that dinosaur die? How long has the Earth been around? When did the Moon form? What about the Universe? How long has that party been going on? Can I drink this beer yet, or will I go blind? How long can Spam remain edible past its expiration date?

As with distance, scientists have developed a range of tools to measure the age of stuff in the Universe. From rocks, to stars, to the Universe itself. Just like distance, it works like a ladder, where certain tools work for the youngest objects, and other tools take over for middle aged stuff, and other tools help to date the most ancient.

Let’s start with the things you can actually get your hands on, like plants, rocks, dinosaur bones and meteorites. Scientists use a technique known as radiometric dating. The nuclear age taught us how to blow up stuff real good, but it also helped understand how elements transform from one element to another through radioactive decay.

For example, there’s a version of carbon, called carbon-14. If you started with a kilo of it, after about 5,730 years, half of it would have turned into carbon-12. And then by 5,730 more years, you’d have about ¼ carbon-14 and ¾ carbon-12.

This is known as an element’s half-life. And so, if you measure the ratio of carbon-12 to carbon-14 in a dead tree, for example, you can calculate how long ago it lived. Different elements work for different ages. Carbon-14 works for the last 50,000 years or so, while Uranium-238 has a half-life of 4.5 billion years, and will let you date the most ancient of rocks. But what about the stuff we can’t touch, like stars?

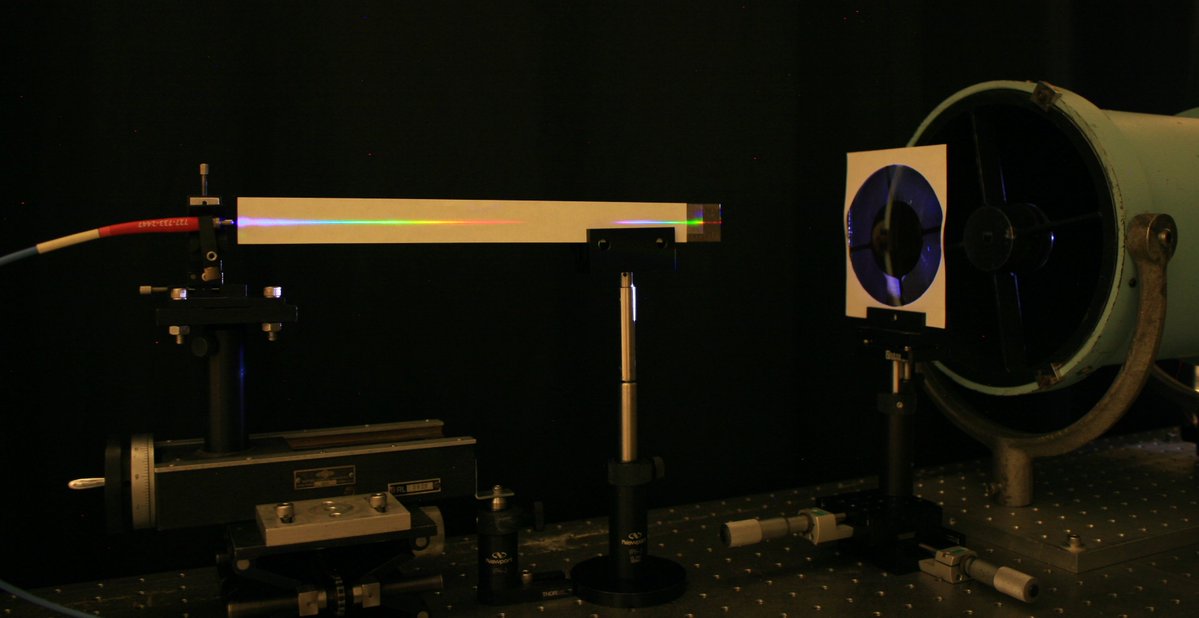

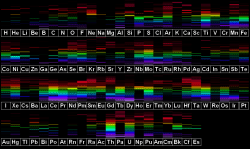

When you use a telescope to view a star, you can break up its light into different colors, like a rainbow. This is known as a star’s spectra, and if you look carefully, you can see black lines, or gaps, which correspond to certain elements. Since they can measure the ratios of different elements, astronomers can just look at a star to see how old it is. They can measure the ratio of uranium-238 to lead-206, and know how long that star has been around. How astronomers know the age of the Universe itself is one of my favorites, and we did a whole episode on this.

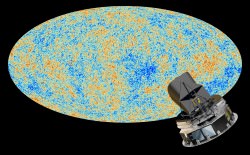

The short answer is, they measure the wavelength of the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation. Since they know this used to be visible light, and has been stretched out by the expansion of the Universe, they can extrapolate back from its current wavelength to what it was at the beginning of the Universe. This tells them the age is about 13.8 billion years. Radiometric dating was a revolution for science. It finally gave us a dependable method to calculate the age of anything and everything, and finally figure out how long everything has been around.

So, fan of our videos. How old are you? Tell us in the comments below.

Thanks for watching! Never miss an episode by clicking subscribe.Our Patreon community is the reason these shows happen. We’d like to thank Ryan Finley and the rest of the members who support us in our quest to make great space and astronomy content every week. Our community members get advance access to episodes, extras, contests, and other shenanigans with Jay, myself and the rest of the team. Want to get in on the action? Click here.