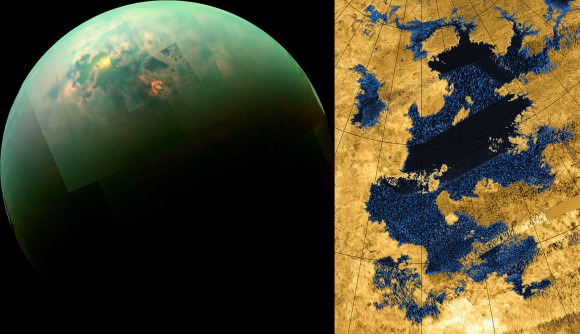

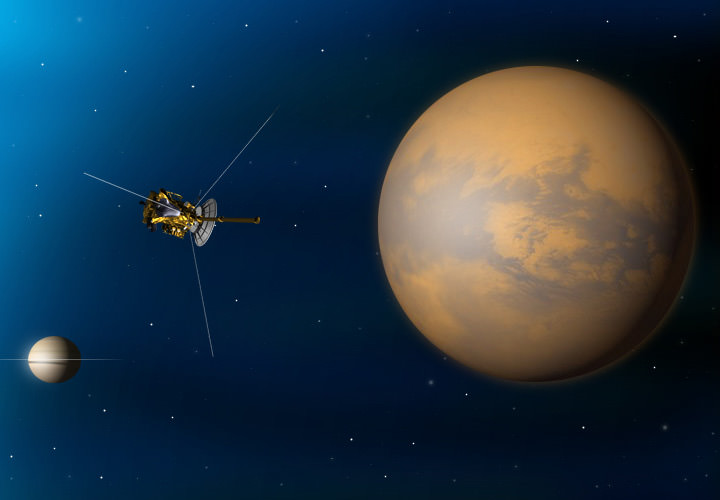

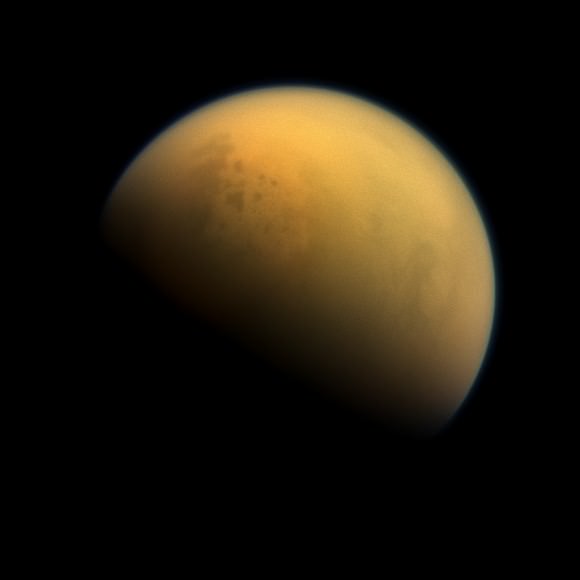

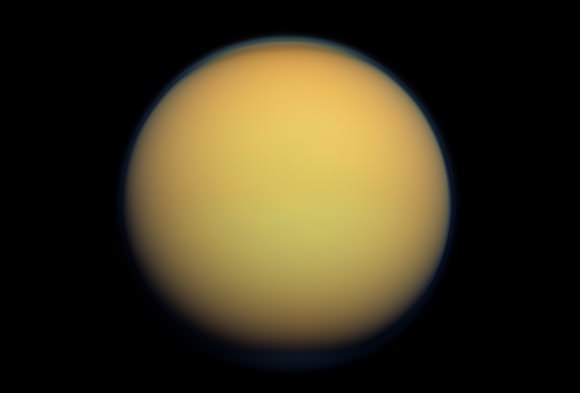

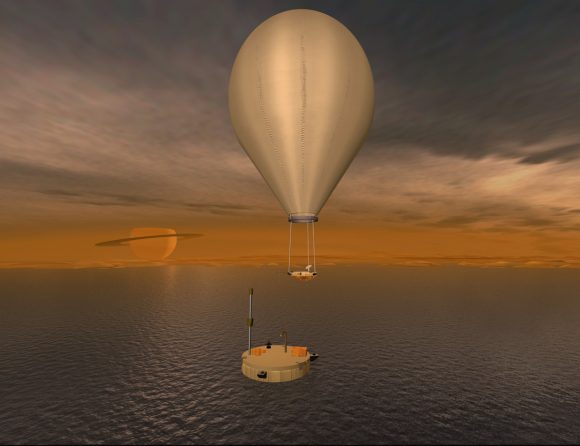

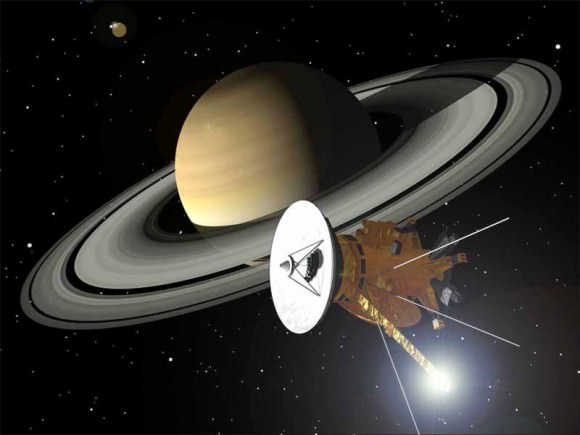

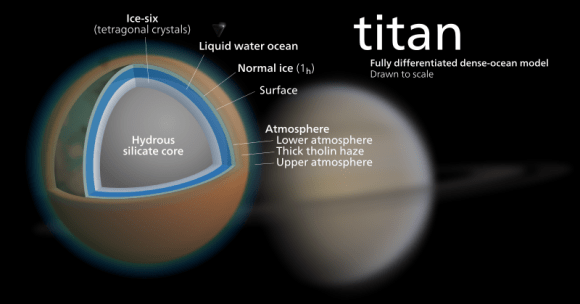

Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, has been a source of mystery ever since scientists began studying it over a century ago. These mysteries have only deepened with the arrival of the Cassini-Huygens mission in the system back in 2004. In addition to finding evidence of a methane cycle, prebiotic conditions and organic chemistry, the Cassini-Huygens mission has also discovered that Titan may have the ingredient that help give rise to life.

Such is the argument made in a recent study by an international team of scientists. After examining data obtained by the Cassini space probe, they identified a negatively charged species of molecule in Titan’s atmosphere. Known as “carbon chain anions”, these molecules are thought to be building blocks for more complex molecules, which could played a key role in the emergence of life of Earth.

The study, titled “Carbon Chain Anions and the Growth of Complex Organic Molecules in Titan’s Ionosphere“, recently appeared in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The team included researchers from University College in London, the University of Grenoble, Uppsalla University, UCL/Birkbeck, the University of Colorado, the Swedish Institute of Space Physics, the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

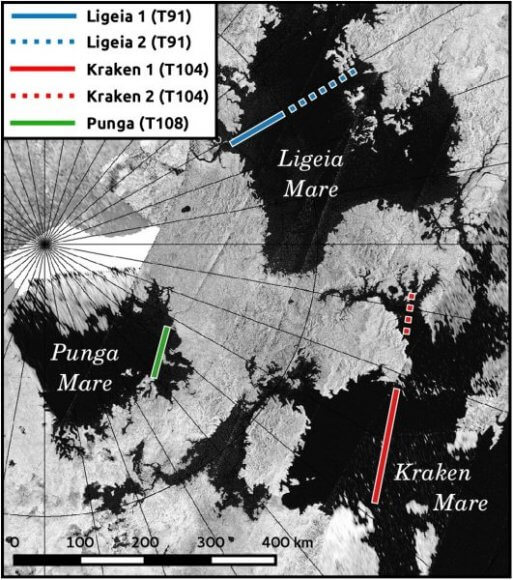

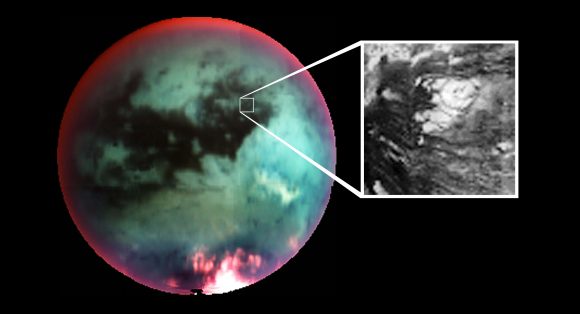

As they indicate in their study, these molecules were detected by the Cassini Plasma Spectrometer (CAPS) as the probe flew through Titan’s upper atmosphere at an distance of 950 – 1300 km (590 – 808 mi) from the surface. They also show how the presence of these molecules was rather unexpected, and represent a considerable challenge to current theories about how Titan’s atmosphere works.

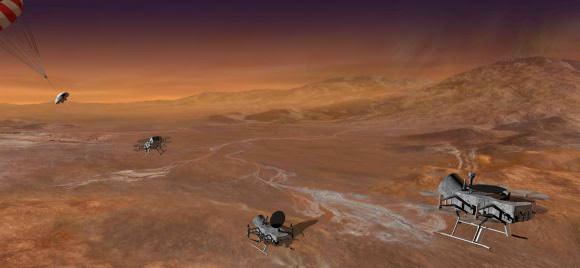

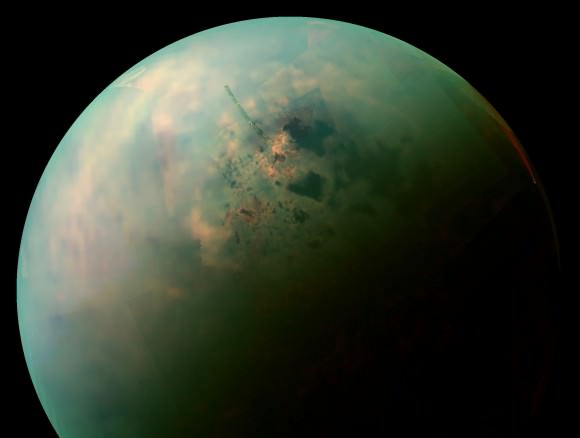

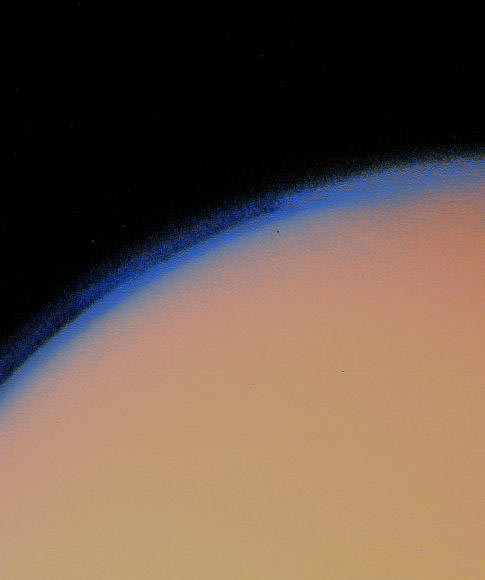

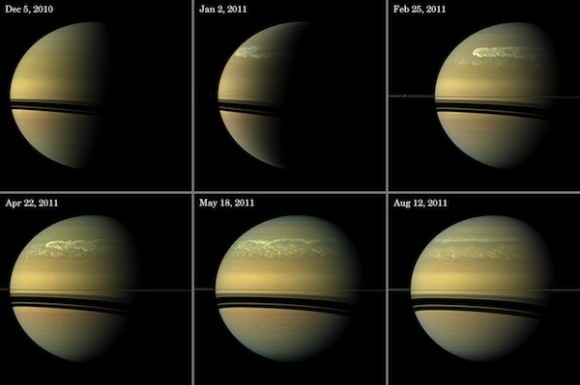

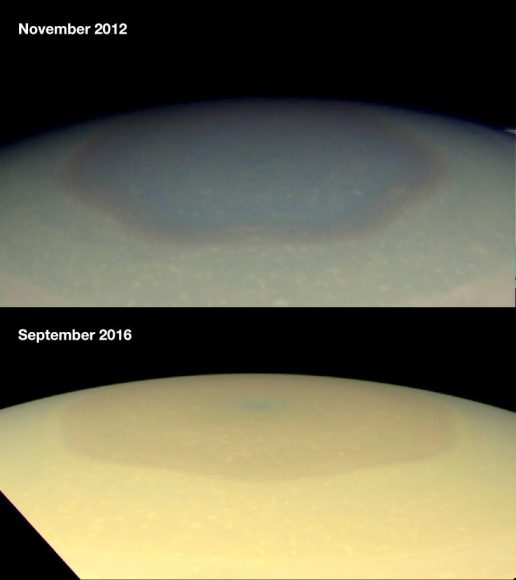

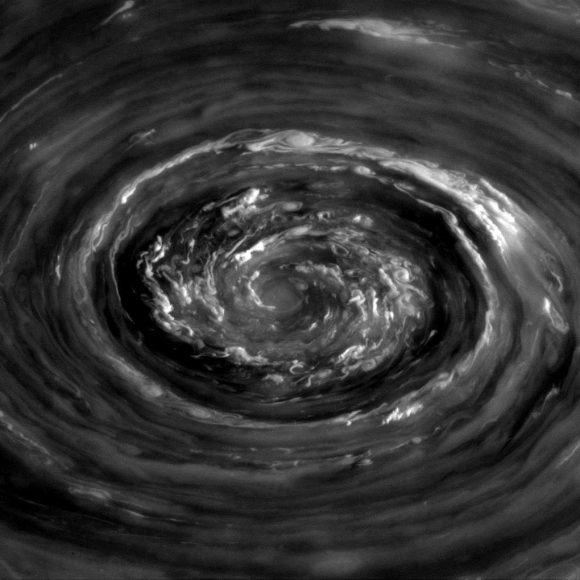

For some time, scientists have understood that within Titan’s ionosphere, nitrogen, carbon and hydrogen are subjected to sunlight and energetic particles from Saturn’s magnetosphere. This exposure drives a process where these elements are transformed into more complex prebiotic compounds, which then drift down towards the lower atmosphere and form a thick haze of organic aerosols that are thought to eventually reach the surface.

This has been the subject of much interest, since the process through which simple molecules form complex organic ones has remained something of a mystery to scientists. This could be coming to an end thanks to the detection of carbon chain anions, though their discovery was altogether unexpected. Since these molecules are highly reactive, they are not expected to last long in Titan’s atmosphere before combining with other materials.

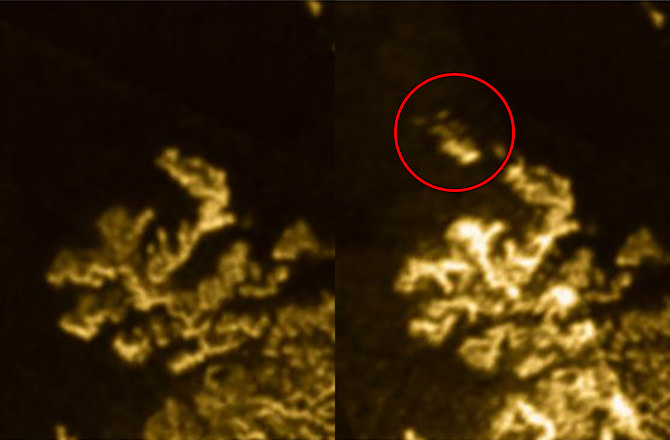

However, the data showed that the carbon chains became depleted closer to the moon, while precursors to larger aerosol molecules underwent rapid growth. This suggests that there is a close relationship between the two, with the chains ‘seeding’ the larger molecules. Already, scientists have held that these molecules were an important part of the process that allowed for life to form on Earth, billions of years ago.

However, their discovery on Titan could be an indication of how life begins to emerge throughout the Universe. As Dr. Ravi Desai, University College London and the lead author of the study, explained in an ESA press release:

“We have made the first unambiguous identification of carbon chain anions in a planet-like atmosphere, which we believe are a vital stepping-stone in the production line of growing bigger, and more complex organic molecules, such as the moon’s large haze particles. This is a known process in the interstellar medium, but now we’ve seen it in a completely different environment, meaning it could represent a universal process for producing complex organic molecules.”

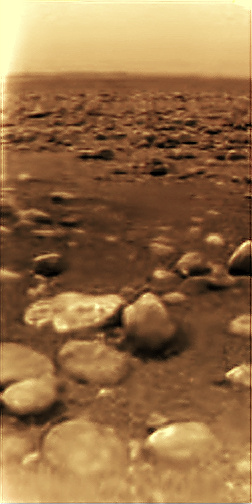

Because of its dense nitrogen and methane atmosphere and the presence of some of the most complex chemistry in the Solar System, Titan is thought by many to be similar to Earth’s early atmosphere. Billions of years ago, before the emergence of microorganisms that allowed for subsequent build-up of oxygen, it is likely that Earth had a thick atmosphere composed of nitrogen, carbon dioxide and inert gases.

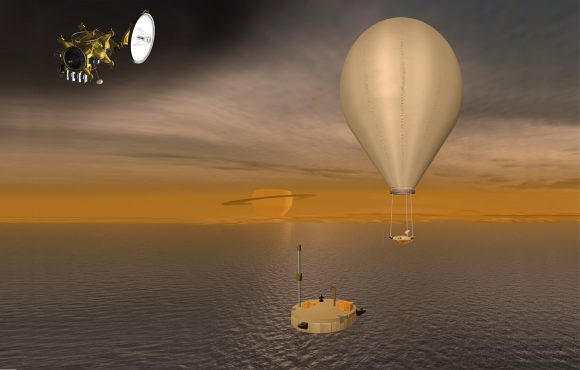

Therefore, Titan is often viewed as a sort planetary laboratory, where the chemical reactions that may have led to life on Earth could be studied. However, the prospect of finding a universal pathway towards the ingredients for life has implications that go far beyond Earth. In fact, astronomers could start looking for these same molecules on exoplanets, in an attempt to determine which could give rise to life.

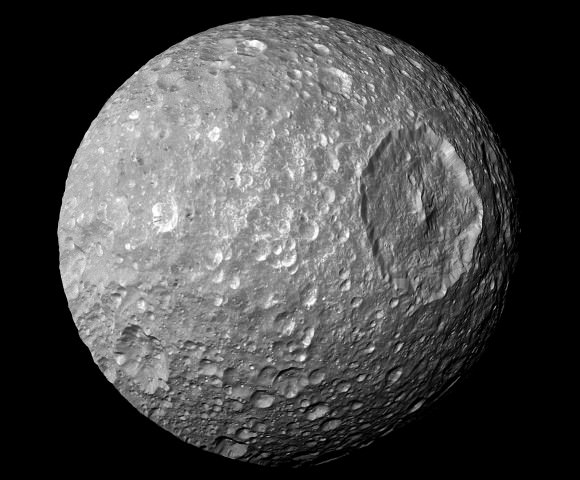

Closer to home, the findings could also be significant in the search for life in our own Solar System. “The question is, could it also be happening within other nitrogen-methane atmospheres like at Pluto or Triton, or at exoplanets with similar properties?” asked Desia. And Nicolas Altobelli, the Project Scientist for the Cassini-Huygens mission, added:

“These inspiring results from Cassini show the importance of tracing the journey from small to large chemical species in order to understand how complex organic molecules are produced in an early Earth-like atmosphere. While we haven’t detected life itself, finding complex organics not just at Titan, but also in comets and throughout the interstellar medium, we are certainly coming close to finding its precursors.“

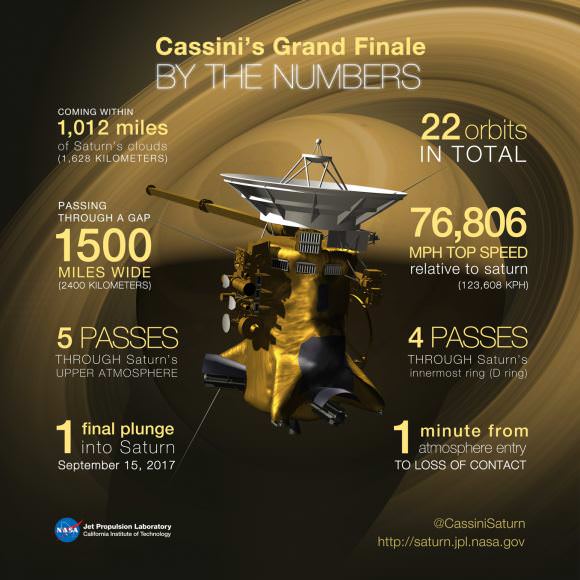

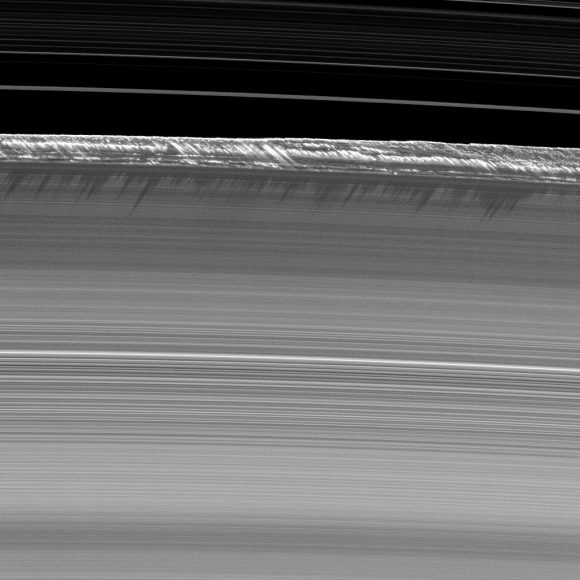

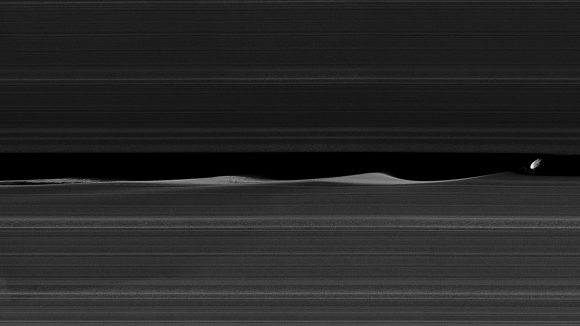

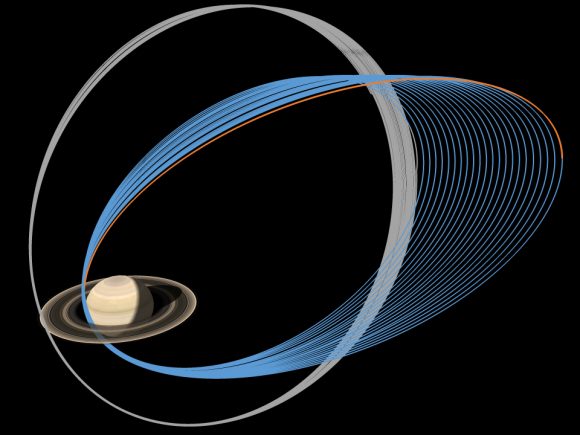

Cassini’s “Grande Finale“, the culmination of its 13-year mission around Saturn and its system of moons, is set to end on September 15th, 2017. In fact, as of the penning of this article, the mission will end in about 1 month, 18 days, 16 hours, and 10 minutes. After making its final pass between Saturn’s rings, the probe will be de-orbited into Saturn’s atmosphere to prevent contamination of the system’s moons.

However, future missions like the James Webb Space Telescope, the ESA’s PLATO mission and ground-based telescopes like ALMA are expected to make some significant exoplanet finds in the coming years. Knowing specifically what kinds of molecules are intrinsic in converting common elements into organic molecules will certainly help narrow down the search for habitable (or even inhabited) planets!

Further Reading: ESA, The Astrophysical Journal Letters