By Mark Thompson

March 18, 2025

After an unexpectedly long mission in orbit, astronauts Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore finally arrived home. Their SpaceX Dragon capsule detached from the International Space Station early Tuesday morning, beginning the de-orbiting process. Nick Hague and Aleksandr Gorbunov are also on board and, following a nail biting descent, finally at 7.58pm EDT today.

Continue reading

By Paul Sutter

March 18, 2025

The most dangerous parts of a supernova explosion are the outputs like X-rays and gamma rays. Even though they only share a small fraction of a supernova’s power, they are extremely dangerous.

Continue reading

By Mark Thompson

March 18, 2025

The Square Kilometre Array (SKA) remains under construction with completion still a few years away. However, engineers recently provided an exciting preview having installed 1,024 of the planned 131,072 antennas and capturing a test image of the sky. The image covers about 25 square degrees and reveals 85 of the brightest known galaxies in the region. Once fully operational, the complete array is expected to detect more than 600,000 galaxies within this same area!

Continue reading

By Matthew Williams

March 18, 2025

Welcome back to our five-part examination of Webb's Cycle 4 General Observations program. In the first and second installments, we examined how some of Webb's 8,500 hours of prime observing time this cycle will be dedicated to

Continue reading

By Brian Koberlein

March 18, 2025

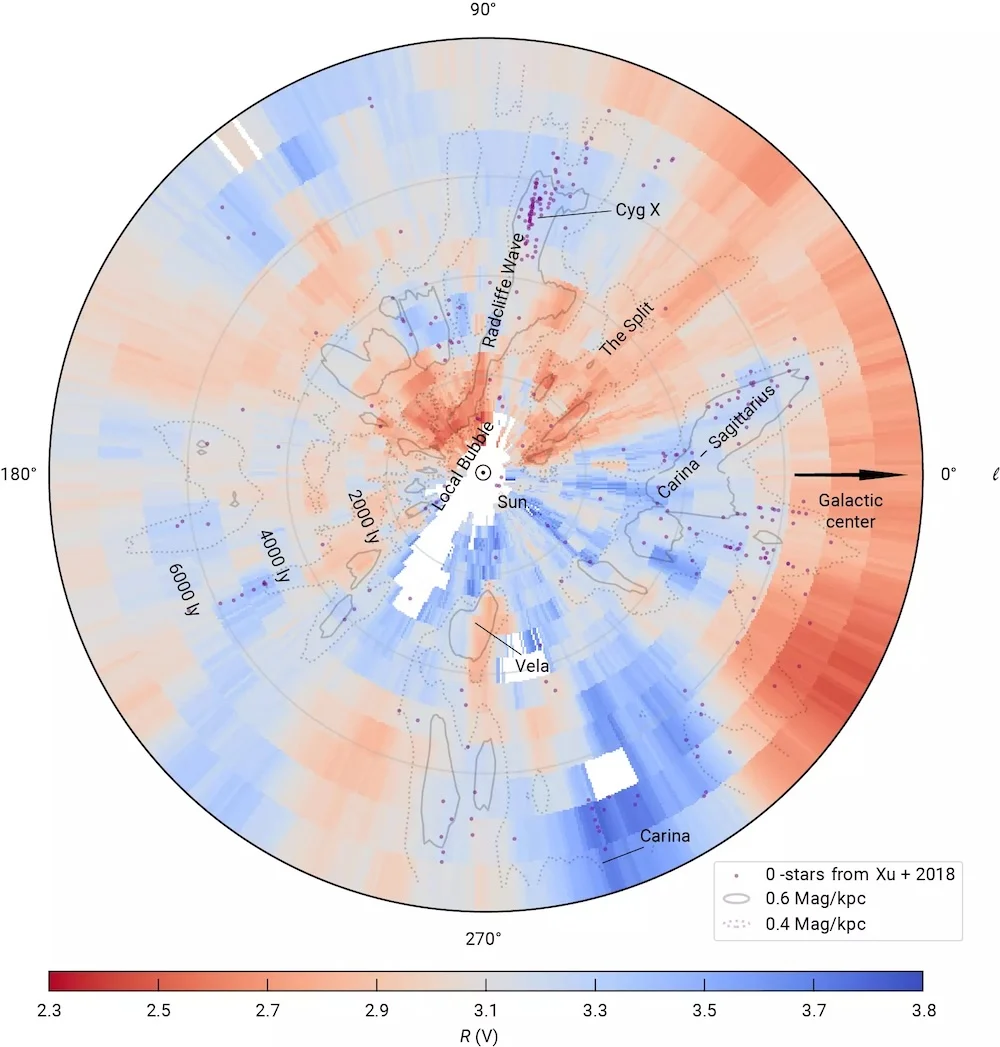

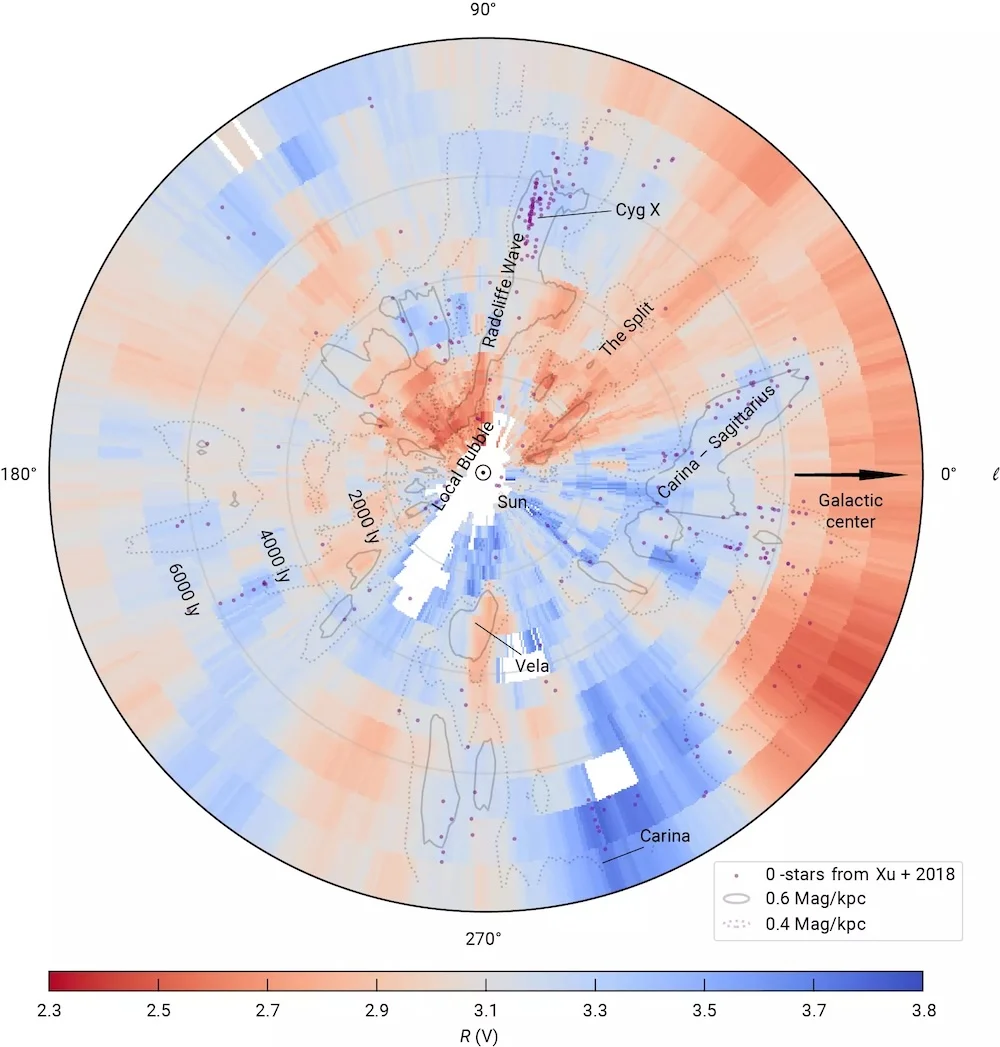

We see the Universe through a glass darkly, or more accurately, through a dusty window. Interstellar dust is scattered throughout the Milky Way, which limits our view depending on where we look. In some directions, the effects of dust are small, but in other regions the view is so dusty it's called the Zone of Avoidance. Dust biases our view of the heavens, but fortunately a new study has created a detailed map of cosmic dust so we can better account for it.

Continue reading

By Evan Gough

March 18, 2025

When massive stars explode as supernovae, they can leave behind neutron stars. Other than black holes, these are the densest objects we know of. However, their masses are difficult to determine. New research is making headway.

In new research published in Nature

Continue reading

By Mark Thompson

March 18, 2025

The search for life has become one of the holy grails of science. With the increasing number of exoplanet discoveries, astronomers are hunting for a chemical that can only be present in the atmosphere of a planet with life! A new paper suggests that methyl halides, which contain one carbon and three hydrogen atoms, may just do the trick. Here on Earth they are produced by bacteria, algae, fungi and some plants but not by any abiotic processes (non biological.) There is a hitch, detecting these chemicals is beyond the reach of current telescopes.

Continue reading

By Mark Thompson

March 18, 2025

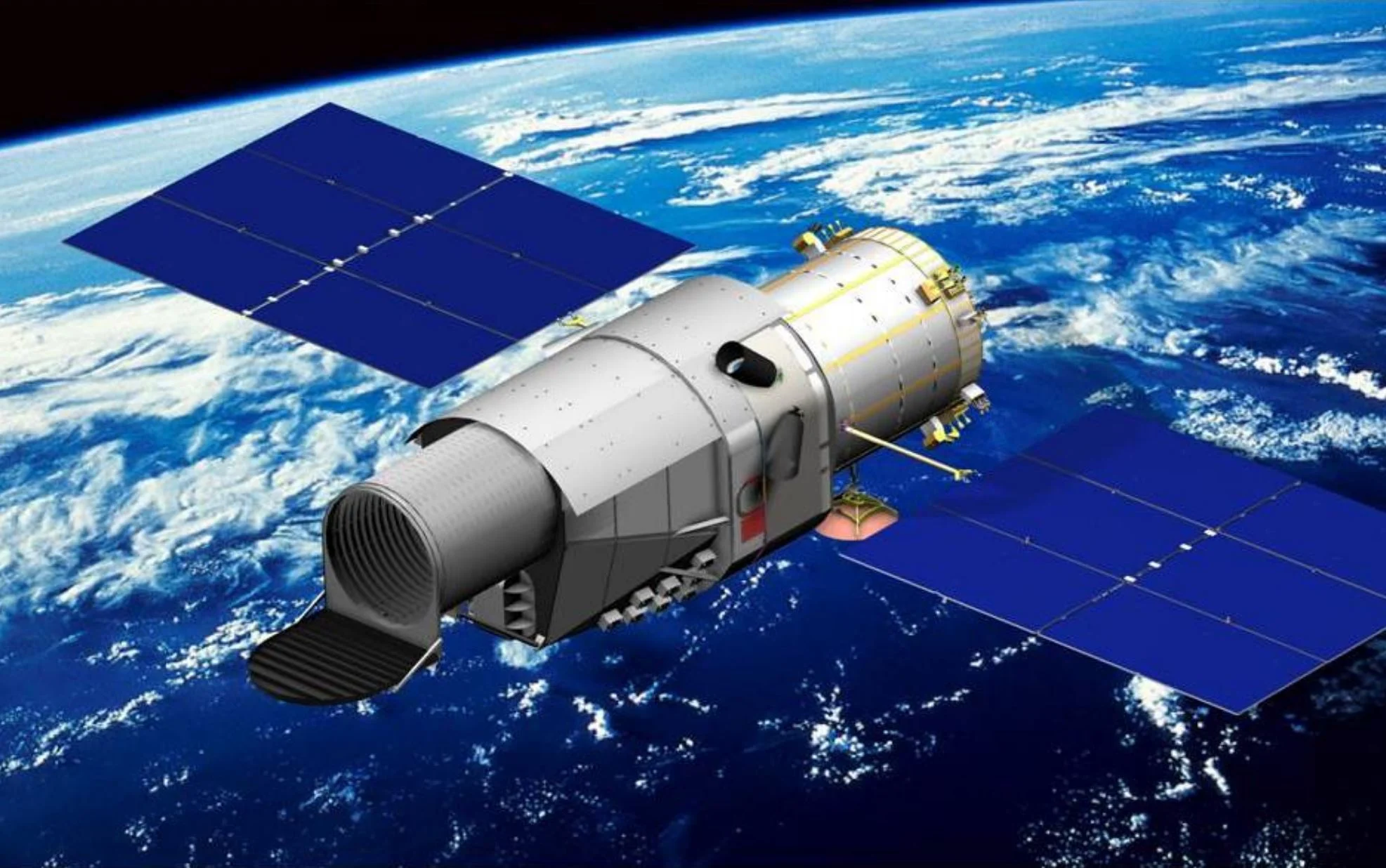

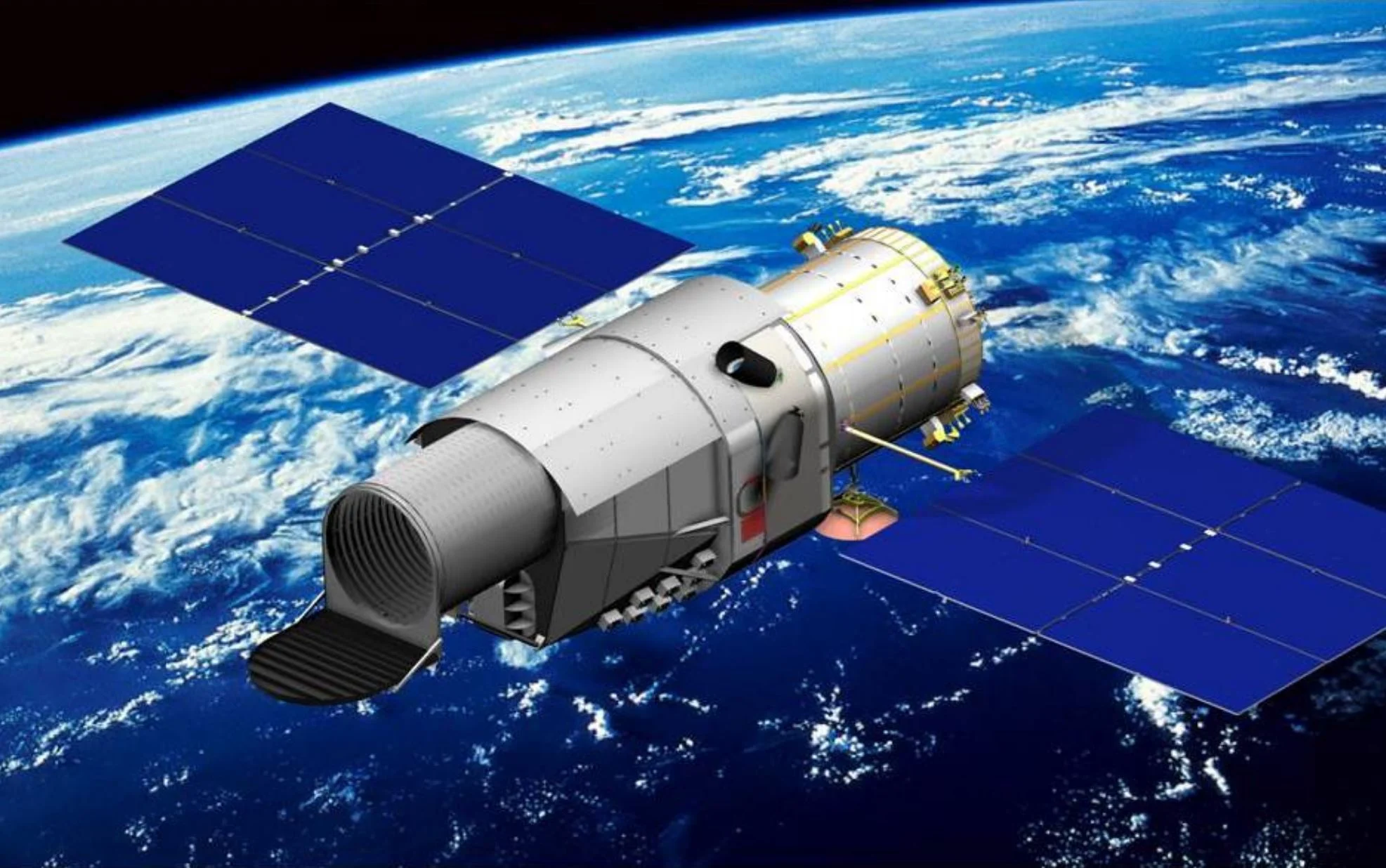

The China Space Station Telescope, scheduled for a 2027 launch, will offer astronomers a fresh view on the cosmos. Though somewhat smaller than Hubble, it features a much wider field of view, giving a wide-field surveys that will map gravitational lensing, galaxy clusters, and cosmic voids. Scientists anticipate it will measure dark energy with 1% precision, differentiate between cold and dark matter models, and evaluate gravitational theories.

Continue reading

By Paul Sutter

March 17, 2025

_(52748025943).png)

From far enough away, most supernovas are benign. But the thing you have to watch out for are the X-rays.

Continue reading

By Evan Gough

March 17, 2025

When water is sprayed or splashed, different size microdroplets develop opposite charges. This "microlightning" could've provided the energy needed to synthesize prebiotic molecules necessary for life.

Continue reading

Universe Today

Universe Today

_(52748025943).png)