Every planet in the Solar System has its own peculiar orbit, and these vary considerably. Whereas planet Earth takes 365.25 days to complete a single orbit about our Sun, Mars takes almost twice as long – 686.971 days. Then you have Jupiter and the other gas giants, which take between 11.86 and 164.8 years to orbit our Sun. But even with these serving as examples, astronomers were not prepared for what they found when they looked at CVSO 30.

This star system, which lies some 1200 light years from Earth, has been found in recent years to have two candidate exoplanets. These planets, which are many times the mass of Jupiter, were discovered by an international team of astronomers using both the Transit Method and Direct Imaging. And what they found was very interesting: one planet has an orbital period of less than 11 days while the other takes a whopping 27,000 years to orbit its parent star!

In addition to being a big surprise, the detection of these two planets using different methods was an historic achievement. Up until now, the vast majority of the over 2,000 exoplanets discovered have been detected thanks to indirect methods. These include the aforementioned Transit Method, which detects planets by measuring the dimming effect they cause when crossing their parent star’s path, and the Radial Velocity Method, which measures the gravitational effect planets have on their parent star.

In 2012, astronomers used the Transit Method to detect CVSO 30b, a planet with 5 to 6 times the mass of Jupiter, and which orbits its star at a distance of only 1.2 million kilometers (by comparison, Mercury orbits our Sun at a distance of 58 million kilometers). From these characteristics, CVSO 30b can be described as a particularly “hot-Jupiter”.

In contrast, Direct Imaging has been used to spot only a few dozen exoplanets. The reason for this is because it is typically quite difficult to detect the light reflected by a planet’s atmosphere due it being drowned out by the light of its parent star. It can also be quite demanding when it comes to the instrument involved. Still, compared to indirect methods, it can be more effective when it comes to exploring the remote regions of a star.

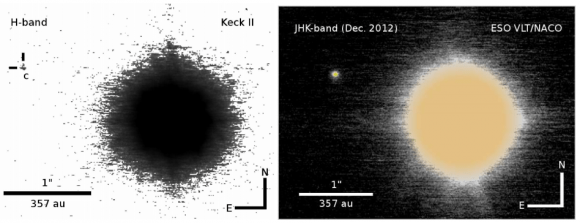

Thanks to the efforts of an international team of astronomers, who combined the use of the Keck Observatory in Hawaii, the ESO’s Very Large Telescope in Chile, and the Spanish National Research Council’s (CSIC) Calar Alto Observatory, CVSO 30c was spotted in remote regions around its parent star, orbiting at a distance of around 666 AU.

The details of the discovery were published in a paper titled “Direct Imaging discovery of a second planet candidate around the possibly transiting planet host CVSO 30“. In it, the researchers – who hail from such prestigious institutions as the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, the Jena Observatory, the European Space Agency and the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy – explained the methods used to find the exoplanet, and the significance of its discovery.

As Tobias Schmidt – of the University of Hamburg, the Astrophysical Institute and University Observatory Jena, and the lead author of the paper – told Universe Today via email:

“[30b and 30c] are both unusual on their own. CVSO 30b is the first transiting planet around a star as young as 2.5 million years. Published in 2012, all previously detected transiting planets were older than few hundred million years… It has been a surprise to find a planetary mass companion at 662 AU, or 662 times the distance from Earth to the Sun, from a primary star having only about 0.4 solar masses. According to the standard model, planets form in disks around the star. But none of the observed disks around such low-mass stars is large enough to form such an object.”

In other words, it is surprising to find two exoplanet candidates with several times the mass of Jupiter (aka. Super-Jupiters) orbiting a star as small as CVSO 30. But to find two exoplanets with such a disparity in terms of their respective distance from their star (despite being similar in mass) was particularly surprising.

Relying on high-contrast photometric and spectroscopic observations from the Very Large Telescope, the Keck telescopes and the Calar Alto observatory, the international team was able to spot 30c using a technique known as lucky imaging. This process, which is used by ground-based telescopes, involves many high-speed, quick exposure photos being taken to minimize atmospheric interference.

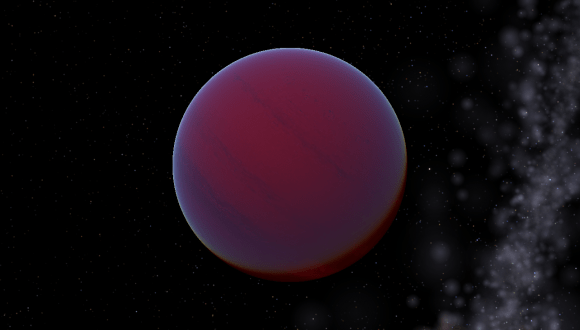

What they found was an exoplanet with a wide orbit that was between 4 and 5 Jupiter masses, and was also very young – less than 10 million years old. What’s more, the spectroscopic data indicated that it is unusually blue for a planet, as most other planet candidates of its kind are very red. The researchers concluded from this that it is likely that 30c is the first young planet of its kind to be directly imaged.

They further concluded that 30 c is also likely the first “L-T transition object” younger than 10 million years to be found orbiting a star. L-T transition objects are a type of brown dwarf – objects that are too large to be considered planets, but too small to be considered stars. Typically they are found embedded in large clouds of gas and dust, or on their own in space.

Paired with its companion – 30 b, which is impossibly close to its parent star – 30 c is not believed to have formed at its current position, and is likely not stable in the long-term. At least, not where current models of planetary formation and orbit are concerned. However, as Prof. Schmidt indicated, this offers a potential explanation for the odd nature of these exoplanets.

“We do think this is a very good hint,” he said, “that the two objects might have formed regularly around the star at a separation comparable to Jupiter or Saturn’s separation from the Sun, then interacted gravitationally and were scattered to their current orbits. However this is still speculation, further investigations will try to prove this. Both have about the same mass of few Jupiter masses, the inner one might be even lower.”

The discovery is also significant since it was the first time that these two detection methods – Transit and Direct Imaging – were used to confirm exoplanet candidates around the same star. In this case, the methods were quite complimentary, and present opportunities to learn more about exoplanets. As Professor Schmidt explained:

“Both Transit method and radial velocity method have problems finding planets around young stars, as the activity of young stars is disturbing the search for them. CVSO 30 b was the first very young planet found with these methods, currently a hand full of candidates exist. Direct imaging, on the other hand, is working best for young planets as they still contract and are thus self-luminous. It is therefore great luck that a far out planet was found around the very first young star hosting a inner planet…

“However, the real advantage of transit and direct imaging methods is that the two objects can now be investigated in greater detail. While we can use the direct light from the imaging for spectroscopy, i.e. split the light according to its wavelength, we hope to achieve the same for the inner planet candidate. This is possible as the light passes through the atmosphere of the planet during transits and some of the elements are absorbed by the composition material of the atmosphere. So we do hope to learn a lot about planet formation, thus also formation of the early Solar System and about young planets in particular from the CVSO 30 system.”

Since astronomers first began began to find exoplanet candidates in distant star systems, we have come to learn just how diverse our Universe really is. Many of the discoveries have challenged our notions about where planets can form around their parent star, while others have showed us that planets can take many different forms.

As time goes on and our exploration of the local Universe advances, we will be challenged to find explanations for how it all fits together. And from that, new and more comprehensive models will no doubt emerge.