[/caption]

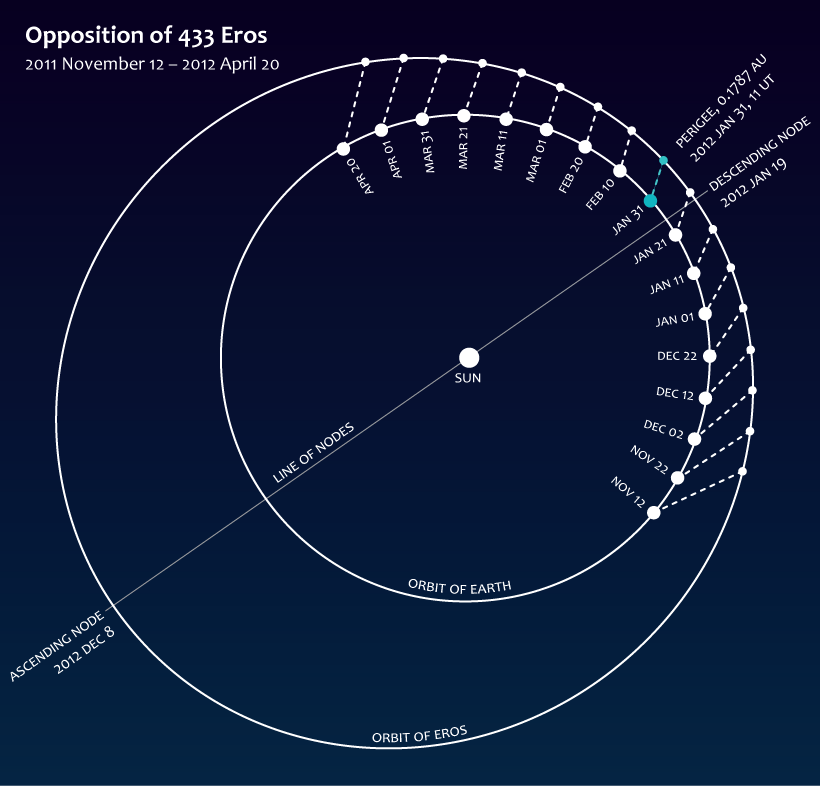

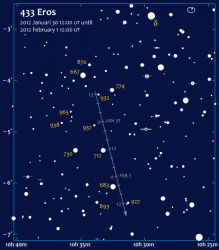

As the bright Mars-crossing asteroid 433 Eros makes its closest approach to Earth since 1975, astronomers around the globe are taking the opportunity to measure its position in the sky, thereby fine-tuning our working knowledge of distances in the solar system. Using the optical principle of parallax, whereby different viewpoints of the same object show slightly shifted positions relative to background objects, skywatchers in different parts of the world can observe Eros over the next few nights and share their images online.

The endeavor is called the Eros Parallax Project, and you can participate too!

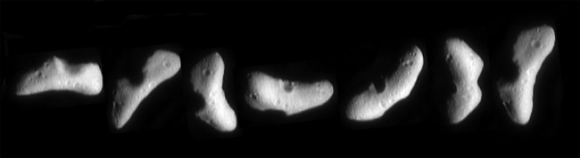

Discovered in 1898, Eros was the largest near-Earth asteroid yet identified. Its close and relatively bright oppositions were calculated by astronomers of the day and used, along with solar transits by Venus (one of which, if you haven’t heard, will also occur this year on June 5!) to calculate distances in the inner solar system.

Having both events take place within the same year offers today’s astronomers an unparalleled opportunity to obtain observational measurements.

Through the efforts of the Astronomers Without Borders organization, along with Steven van Roode and Michael Richmond from the Transit of Venus project, anyone with moderate astrophotography experience can participate in the observation of Eros and share their photos via free online software.

Using the data gathered by individual participants positioned around the world, each with their own specific viewpoints, astronomers will be able to precisely measure the distance to Eros.

The more accurately that distance is known, the more accurately the distance from Earth to the Sun can be calculated – via the orbital mechanics of Kepler’s third law.

The last time such a bright pass of Eros occurred was in January of 1931. Observations of the asteroid made at that time allowed astronomers to calculate a solar parallax of 8″ .790, the most accurate up to that time and the most accurate until 1968, when data acquired by radar measurements gave more detailed measurements.

In many ways the 2012 close approach by Eros – astronomically close, but still a very safe 16.6 million miles (26.7 million km) away – will allow for a re-eneactment of the 1931 event… with the exception that this time amateur skywatchers will also contribute data, instantly, from all over the world!

One has to wonder…when Eros comes this close again in 2056, what sort of technology will we use to watch it then…

Find out more about the Eros Parallax Project and how to participate here.

And be sure to check out the article about the project on Astronomers Without Borders as well.