Planet-watchers, some exciting news: you know how we keep talking about planet candidates, those planets that have yet to be confirmed, when we reveal stories about other worlds? That’s because verifying that the slight dimming of a star’s light is due to a planet takes time – -specifically, to have other telescopes verify it through examining gravitational wobbles on the parent star.

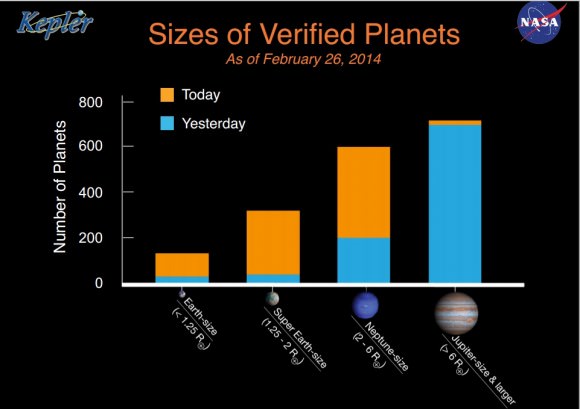

Turns out there’s a way to solve the so-called “bottleneck” of planet candidates vs. confirmed planets. NASA has made use of a new technique that they say will work for multi-planet systems, one that already has results: a single Kepler release of data today (Feb. 26) yielded 715 new planets in one shot. That almost doubles the amount of known planets found before today, which was just under 1,000, officials said.

“This is the largest windfall of planets, not exoplanet candidates, but actual verified exoplanets announced at one time,” said Doug Hudgins, a NASA exoplanet exploration program scientist based in Washington, D.C., at a press conference today. What’s more, among the release were four planets (about double to 2.5 times the size of Earth) that could be considered habitable: Kepler-174 d, Kepler-296 f, Kepler-298 d, Kepler-309 c.

The findings were based on scouring the first two of Kepler’s four years of data, so scientists expect there will be a lot more to come once they go through the second half. Most of the discoveries were planets close to Earth’s size, showing that small planets are common in multiplanetary systems.

These planets, however, are crowded into insanely compact multiple planet systems, sometimes within the reaches of the equivalent of Mercury’s or Venus’ orbits. It’s raising questions about how young systems would have enough material in those reaches to form planets. Perhaps planetary migration played a role, but that’s still poorly understood.

Discoveries of these worlds was made with a new technique called “verification by multiplicity”. The challenge with the method Kepler uses — watching for starlight dimming when a planet passes in front of it — is there are other ways that same phenomenon can occur. One common reason is if the star being observed is a binary star and the second star is just barely grazing the first.

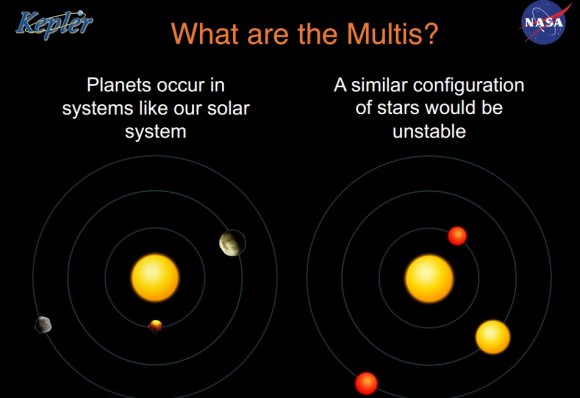

This is how the technique works: If you can imagine a star with a bunch of other stars around it, the mutual gravities of each object would throw their relative orbits into chaos. A star with a bunch of planets, however, would have a more stable orbital configuration. So if scientists see multiple transits of objects across a star’s face, the assumption is that it would be several planets.

“This physical difference, the fact you can’t have multiple star systems that look like planetary systems, is the basis of the validation by multiplicity,” said Jack Lissauer, a planetary scientist at the NASA Ames Research Center who was involved in the research.

Although this is a new technique, the astronomers said there has been at least one published publication talking about this method, and they added that two papers based on their own research have been accepted for publication in the peer-reviewed Astrophysical Journal.

There’s been a lot of attention on Kepler lately, not only because of its planetary finds, but also its uncertain status. In May 2013, a second of its four reaction wheels (or gyroscopes) went down, robbing the probe of its primary mission: to seek planets transiting in front of their stars in a spot in the Cygnus constellation. Since then, scientists have been working on a new method of finding planets with the spacecraft.

Called K2, it would essentially use the sun’s photon “push” on the spacecraft as a way to stabilize Kepler long enough to peer at different areas of the sky throughout the year. The mission is now at a senior-level review process and a decision is expected around May this year.

The spacecraft is good to go for K2 physically, NASA added, as the spacecraft only has four major malfunctions: the two reaction wheels, and 2 (out of 21) “science modules” that are used for science observing. The first module failed early in the mission, while the second died during a recent K2 test. While the investigation is ongoing, NASA said that they expect it will be due to an isolated part failure and that it will have no measurable impact on doing K2.

Edit, 8:30 p.m. EST: The two papers related to the Kepler discovery are available here and here on the prepublishing site Arxiv. Both are accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal. (Hat tip to Tom Barclay).