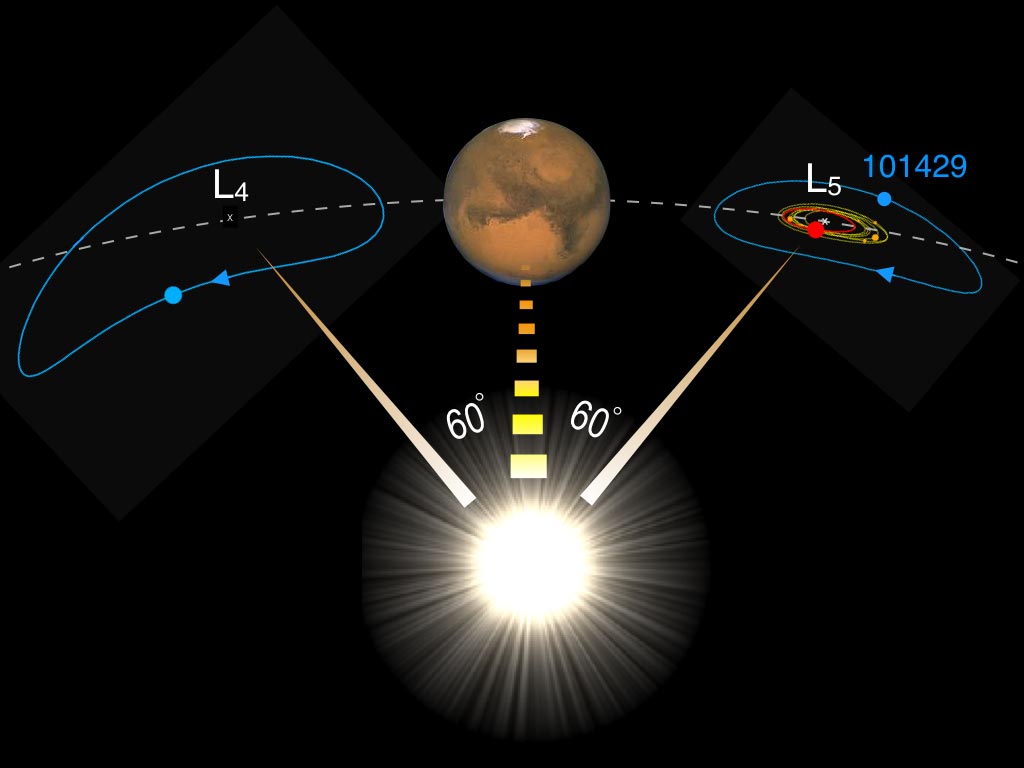

Although Mars is much smaller than Earth, it has two moons. Deimos and Phobos were probably once asteroids that were captured by the gravity of Mars. The red planet has also captured nine other small bodies. These asteroids don’t orbit Mars directly, but instead, orbit gravitationally stable points on either side of the planet known as Lagrange points. They are known as trojans, and they move along the Martian orbit about 60° ahead or behind Mars. Most of these trojans seem to be of Martian origin and formed from asteroid impacts with Mars. But one of the trojans seems to have a different origin.

Continue reading “One Mars Trojan asteroid has the same chemical signature as the Earth’s moon”New Ideas for the Mysterious Tabby’s Star: a Gigantic Planet or a Planet With Rings

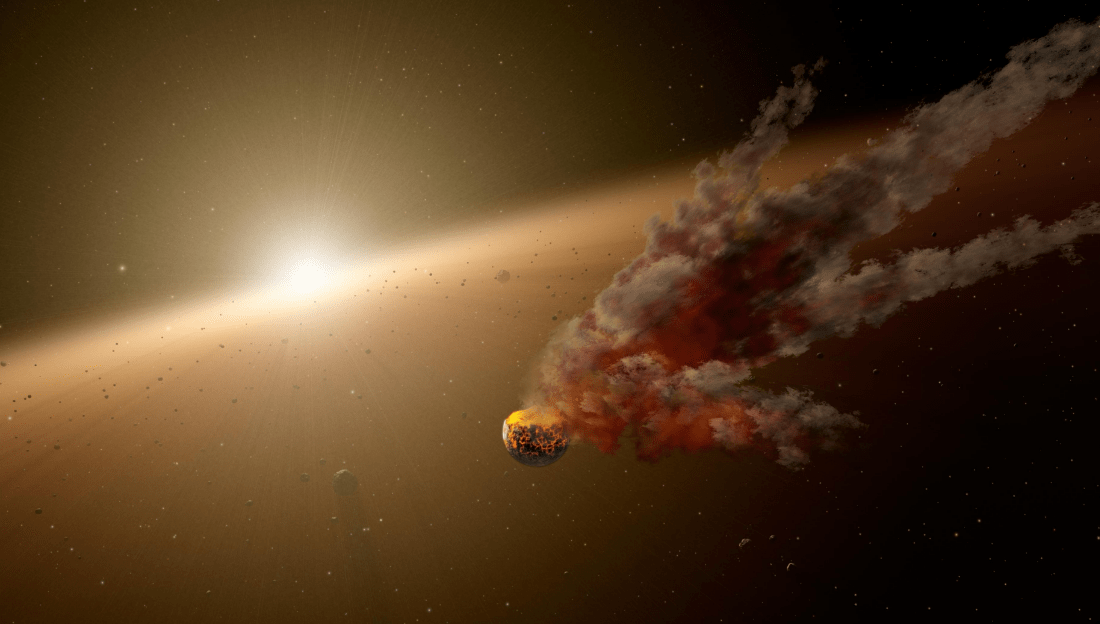

KIC 8462852 (aka. Tabby’s Star) captured the world’s attention back in September of 2015 when it was found to be experiencing a mysterious drop in brightness. A week ago (on May 18th), it was announced that the star was at it again, which prompted observatories from all around the world to train their telescopes on the star so they could observe the dimming as it happened.

And just like before, this mysterious behavior has fueled speculation as to what could be causing it. Previously, ideas ranged from transiting comets and a consumed planet to alien megastructures. But with the latest studies to be produced on the subject, the light curve of the star has been respectively attributed to the presence of a debris disk and Trojan asteroids in the system and a ring system in the outer Solar System. Continue reading “New Ideas for the Mysterious Tabby’s Star: a Gigantic Planet or a Planet With Rings”

Five New Neptunian Trojans Discovered

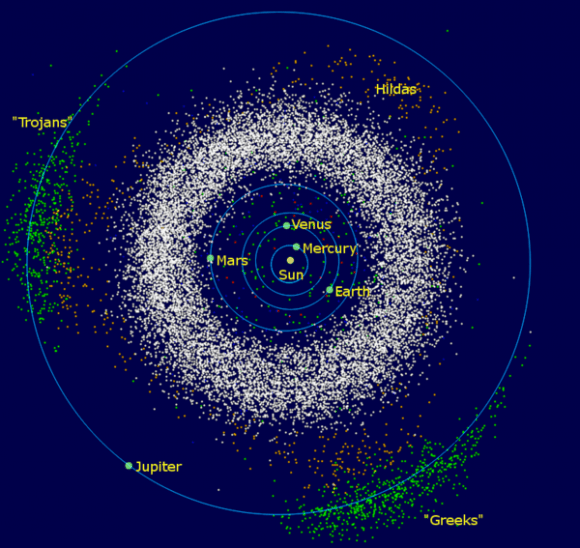

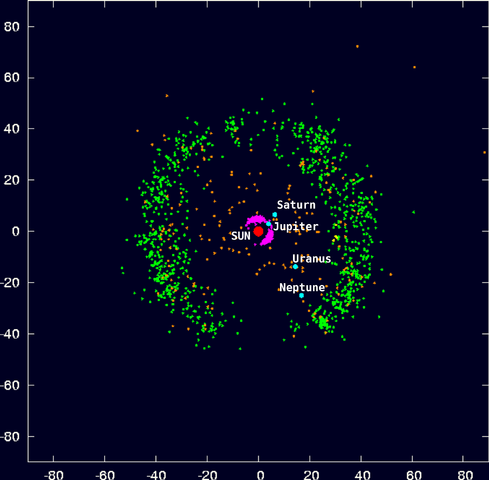

The Solar System is filled with what are known as Trojan Asteroids – objects that share the orbit of a planet or larger moon. Whereas the best-known Trojans orbit with Jupiter (over 6000), there are also well-known Trojans orbiting within Saturn’s systems of moons, around Earth, Mars, Uranus, and even Neptune.

Until recently, Neptune was thought to have 12 Trojans. But thanks to a new study by an international team of astronomers – led by Hsing-Wen Lin of the National Central University in Taiwan – five new Neptune Trojans (NTs) have been identified. In addition, the new discoveries raise some interesting questions about where Neptune’s Trojans may come from.

For the sake of their study – titled “The Pan-STARRS 1 Discoveries of Five New Neptune Trojans“- the team relied on data obtained by the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS). This wide-field imaging facility – which was founded by the University of Hawaii’s Institute for Astronomy – has spent the last decade searching the Solar System for asteroids, comets, and Centaurs.

The team used data obtained by the PS-1 survey, which ran from 2010 to 2014 and utilized the first Pan-STARR telescope on Mount Haleakala, Hawaii. From this, they observed seven Trojan asteroids around Neptune, five of which were previously undiscovered. Four of the TNs were observed orbiting within Neptune’s L4 point, and one within its L5 point.

The newly detected objects have sizes ranging from 100 to 200 kilometers in diameter, and in the case of the L4 Trojans, the team concluded from the stability of their orbits that they were likely primordial in origin. Meanwhile, the lone L5 Trojan was more unstable than the other four, which led them to hypothesize that it was a recent addition.

As Professor Lin explained to Universe Today via email:

“The 2 of the 4 currently known L5 Neptune Trojans, included the one L5 we found in this work, are dynamically unstable and should be temporary captured into Trojan cloud. On the other hand, the known L4 Neptune Trojans are all stable. Does that mean the L5 has higher faction of temporary captured Trojans? It could be, but we need more evidence.”

In addition, the results of their simulation survey showed that the newly-discovered NT’s had unexpected orbital inclinations. In previous surveys, NTs typically had high inclinations of over 20 degrees. However, in the PS1 survey, only one of the newly discovered NTs did, whereas the others had average inclinations of about 10 degrees.

From this, said Lin, they derived two possible explanations:

“The L4 “Trojan Cloud” is wide in orbital inclination space. If it is not as wide as we thought before, the two observational results are statistically possible to generate from the same intrinsic inclination distribution. The previous study suggested >11 degrees width of inclination, and most likely is ~20 degrees. Our study suggested that it should be 7 to 27 degrees, and the most likely is ~ 10 degrees.”

“[Or], the previous surveys were used larger aperture telescopes and detected fainter NT than we found in PS1. If the fainter (smaller) NTs have wider inclination distribution than the larger ones, which means the smaller NTs are dynamically “hotter” than the larger NTs, the disagreement can be explained.”

According to Lin, this difference is significant because the inclination distribution of NTs is related to their formation mechanism and environment. Those that have low orbital inclinations could have formed at Neptune’s Lagrange Points and eventually grew large enough to become Trojans asteroids.

On the other hand, wide inclinations would serve as an indication that the Trojans were captured into the Lagrange Points, most likely during Neptune’s planetary migration when it was still young. And as for those that have wide inclinations, the degree to which they are inclined could indicate how and where they would have been captured.

“If the width is ~ 10 degrees,” he said, “the Trojans can be captured from a thin (dynamically cold) planetesimal disk. On the other hand, if the Trojan cloud is very wide (~ 20 degrees), they have to be captured from a thick (dynamically hot) disk. Therefore, the inclination distribution give us an idea of how early Solar system looks like.”

In the meantime, Li and his research team hope to use the Pan-STARR facility to observe more NTs and hundreds of other Centaurs, Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs) and other distant Solar System objects. In time, they hope that further analysis of other Trojans will shed light on whether there truly are two families of Neptune Trojans.

This was all made possible thanks to the PS1 survey. Unlike most of the deep surveys, which are only ale to observe small areas of the sky, the PS1 is able to monitor the whole visible sky in the Northern Hemisphere, and with considerable depth. Because of this, it is expected to help astronomers spot objects that could teach us a great deal about the history of the early Solar System.

Further Reading: arXiv

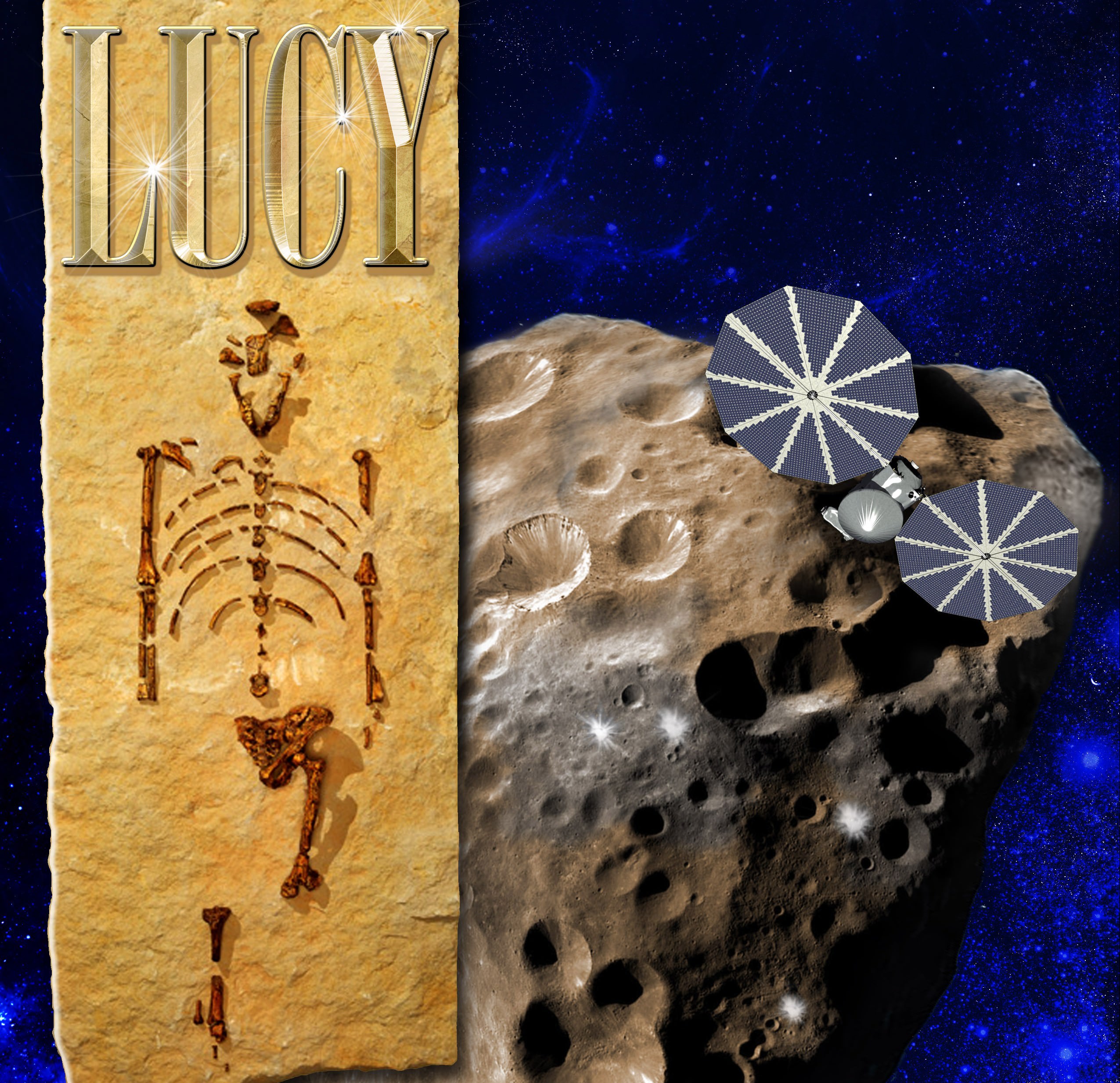

Surveying the “Fossils of Planet Formation”: The Lucy Mission

In February of 2014, NASA’s Discovery Program put out the call for mission proposals, one or two of which will have the honor of taking part in Discovery Mission Thirteen. Hoping to focus the next round of exploration efforts to places other than Mars, the five semifinalists (which were announced this past September) include proposed missions to Venus, Near-Earth Objects, and asteroids.

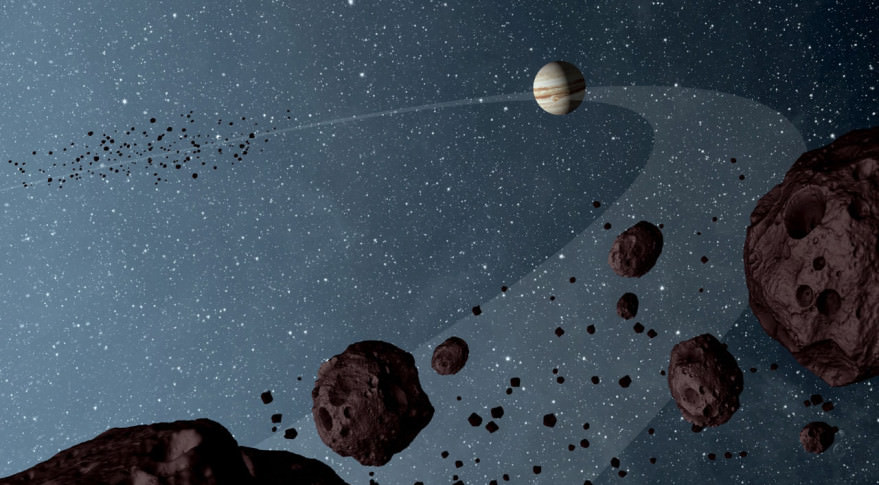

When it comes to asteroid exploration, one of the possible contenders is Lucy – a proposed reconnaissance orbiter that would study Jupiter‘s Trojan Asteroids. In addition to being the first mission of its kind, examining the Trojans Asteroids could also lead to several scientific finds that will help us to better understand the history of the Solar System.

By definition, Trojan are populations of asteroids that share their orbit with other planets or moons, but do not collide with it because they orbit in one of the two Lagrangian points of stability. The most significant population of Trojans in the Solar System are Jupiter’s, with a total of 6,178 having been found as of January 2015. In accordance with astronomical conventions, objects found in this population are named after mythical figures from the Trojan War.

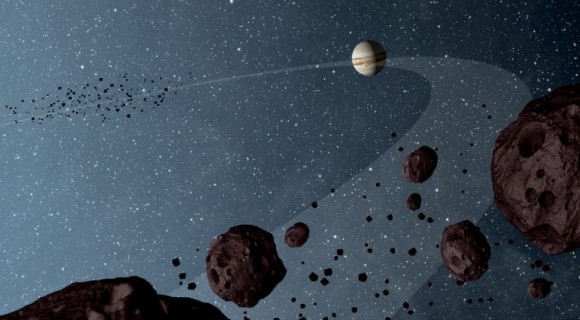

There are two main theories as to where Jupiter’s Trojans came from. The first suggests that they formed in the same part of the Solar System as Jupiter and were caught by the gas giant’s gravity as it accumulated hydrogen and helium from the protoplanetary disk. Since they would have shared the same approximate orbit as the forming gas giant, they would have been caught in its gravity and orbited it ever since.

The second theory, part of the Nice model, proposes that the Jupiter Trojans were captured about 500-600 million years after the Solar System’s formation. During this period Uranus, Neptune – and to a lesser extent, Saturn – moved outward, whereas Jupiter moved slightly inward. This migration could have destabilized the primordial Kuiper Belt, throwing millions of objects into the inner Solar System, some of which Jupiter then captured.

In either case, the presence of Trojan asteroids around Jupiter can be traced back to the early Solar System. Studying them therefore presents an opportunity to learn more about its history and formation. And if in fact the Trojans are migrant from the Kuiper Belt, it would also be a chance for scientists to learn more about the most distant reaches of the solar system without having to send a mission all the way out there.

The mission would be led by Harold Levison of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado, with the Goddard Space Center managing the project. Its targets would most likely include asteroid (3548) Eurybates, (21900) 1999 VQ10, (11351) 1997 TS25, and the binary (617) Patroclus/Menoetius. It would also visit a main-belt asteroid (1981 EQ5) on the way.

The spacecraft would perform scans of the asteroids and determine their geology, surface features, compositions, masses and densities using a sophisticated suite of remote-sensing and radio instruments. In addition, during it’s proposed 11-year mission, Lucy would also gather information on the asteroids thermal and other physical properties from close range.

The project is named Lucy in honor of one of the most influential human fossils found on Earth. Discovered in the Awash Valley of Ethiopia in 1974, Lucy’s remains – several hundred bone fragments that belonged to a member the hominid species of Australopithecus afarensis – proved to be an extraordinary find that advanced our knowledge of hominid species evolution.

Levison and his team are hoping that a similar find can be made using the probe of the same name. As he and his colleagues describe it, the Lucy mission is aimed at “Surveying the diversity of Trojan asteroids: The fossils of planet formation.”

“This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” said Levinson. “Because the Trojan asteroids are remnants of that primordial material, they hold vital clues to deciphering the history of the solar system. These asteroids are in an area that really is the last population of objects in the solar system to be visited.”

The payload is expected to include three complementary imaging and mapping instruments, including a color imaging and infrared mapping spectrometer, a high-resolution visible imager, and a thermal infrared spectrometer. NASA has also offered an additional $5 to $30 million in funding if mission planners choose to incorporate a laser communications system, a 3D woven heat shield, a Deep Space atomic clock, and/or ion engines.

As one of the semifinalists, the Lucy mission has received $3 million dollars to conduct concept design studies and analyses over the course of the next year. After a detailed review and evaluation of the concept studies, NASA will make the final selections by September 2016. In the end, one or two missions will receive the mission’s budget of $450 million (not including launch vehicle funding or post-launch operations) and will be launched by 2020 at the earliest.

Some Planet-like Kuiper Belt Objects Don’t Play “Nice”

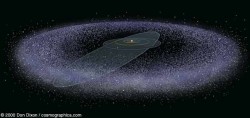

The Kuiper belt — the region beyond the orbit of Neptune inhabited by a number of small bodies of rock and ice — hides many clues about the early days of the Solar System. According to the standard picture of Solar System formation, many planetesimals were born in the chaotic region where the giant planets now reside. Some were thrown out beyond the orbit of Neptune, while others stayed put in the form of Trojan asteroids (which orbit in the same trajectory as Jupiter and other planets). This is called the Nice model.

However, not all Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) play nicely with the Nice model.

(I should point out that the model is named named for the city in France and therefore pronounced “neese”.) A new study of large scale surveys of KBOs revealed that those with nearly circular orbits lying roughly in the same plane as the orbits of the major planets don’t fit the Nice model, while those with irregular orbits do. It’s a puzzling anomaly, one with no immediate resolution, but it hints that we need to refine our Solar System formation models.

This new study is described in a recently released paper by Wesley Fraser, Mike Brown, Alessandro Morbidelli, Alex Parker, and Konstantin Baygin (to be published in the Astrophysical Journal, available online). These researchers combined data from seven different surveys of KBOs to determine roughly how many of each size of object are in the Solar System, which in turn is a good gauge of the environment in which they formed.

The difference between this and previous studies is the use of absolute magnitudes — a measure of how bright an object really is — as opposed to their apparent magnitudes, which are simply how bright an object appears. The two types of magnitude are related by the distance an object is from Earth, so the observational challenge comes down to accurate distance measurements. Absolute magnitude is also related to the size of an KBO and its albedo (how much light it reflects), both important physical quantities for understanding formation and composition.

Finding the absolute magnitudes for KBOs is more challenging than apparent magnitudes for obvious reasons: these are small objects, often not resolved as anything other than points of light in a telescope. That means requires measuring the distance to each KBO as accurately as possible. As the authors of the study point out, even small errors in distance measurements can have a large effect on the estimated absolute magnitude.

In terms of orbits, KBOs fall into two categories: “hot” and “cold”, confusing terms having nothing to do with temperature. The “cold” KBOs are those with nearly circular orbits (low eccentricity, in mathematical terms) and low inclinations, meaning their trajectories lie nearly in the ecliptic plane, where the eight canonical planets also orbit. In other words, these objects have nearly planet-like orbits. The “hot” KBOs have elongated orbits and higher inclinations, behavior more akin to comets.

The authors of the new study found that the hot KBOs have the same distribution of sizes as the Trojan asteroids, meaning there are the same relative number of small, medium, and large KBOs and similarly sized Trojans. That hints at a probable common origin in the early days of the Solar System. This is in line with the Nice model, which predicts that, as they migrated into their current orbits, the giant planets kicked many planetesimals out beyond Neptune.

However, the cold KBOs don’t match that pattern at all: there are fewer large KBOs relative to smaller objects. To make matters more strange, both hot and cold seem to follow the same pattern for the smaller bodies, only deviating at larger masses, which is at odds with expectations if the cold KBOs formed where they orbit today.

To put it another way, the Nice model as it stands could explain the hot KBOs and Trojans, but not the cold. That doesn’t mean all is lost, of course. The Nice model seems to do very well except for a few nagging problems, so it’s unlikely that it’s completely wrong. As we’ve learned from studying exoplanet systems, planet formation models are a work in progress — and astronomers are an ingenious lot.

Earth’s First Trojan Asteroid Discovered

[/caption]

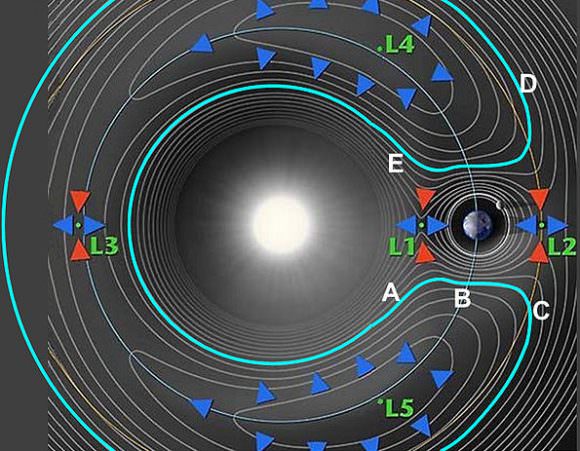

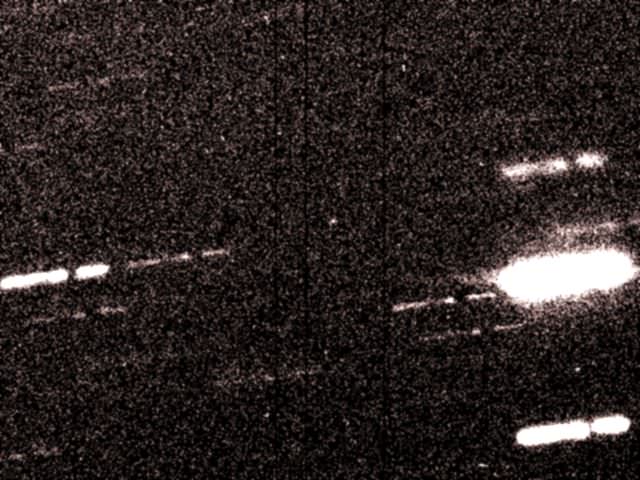

The first known “Trojan” asteroid in Earth’s orbit has been discovered. A Trojan asteroid shares an orbit with a larger planet or moon, but does not collide with it because it orbits around one of two Lagrangian points. Trojans sharing an orbit with Earth have been predicted but never found until now. Astronomers analyzing data from the asteroid-hunting WISE telescope – which ceased operations in February 2011 – found the asteroid, named 2010 TK7, and followup observations with the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawaii confirmed the discovery and the object’s stealthy orbit.

In our solar system, we know of Trojans that share orbits with Neptune, Mars and Jupiter. Two of Saturn’s moons share orbits with Trojans. Astronomers have known that Earth Trojans would be difficult to find because they are relatively small and appear near the sun from Earth’s point of view.

But 2010 TK7 proves that Trojans associated to Earth can be found, and astronomers predict that since one has been found, perhaps they’ll find more, as we’ll learn more about their dynamics and characteristics of their population from this first one.

“These asteroids dwell mostly in the daylight, making them very hard to see,” said Martin Connors of Athabasca University in Canada, lead author of a new paper on the discovery in the July 28 issue of the journal Nature. “But we finally found one, because the object has an unusual orbit that takes it farther away from the sun than what is typical for Trojans. WISE was a game-changer, giving us a point of view difficult to have at Earth’s surface.”

The animation below shows the orbit of 2010 TK7 (green dots).

The asteroid is roughly 1,000 feet (300 meters) in diameter. It has an unusual orbit that traces a complex motion near the L4 point. However, the asteroid also moves above and below the plane. The object is about 50 million miles (80 million kilometers) from Earth. The asteroid’s orbit is well-defined and for at least the next 100 years, it will not come closer to Earth than 15 million miles (24 million kilometers).

“It’s as though Earth is playing follow the leader,” said Amy Mainzer, the principal investigator of WISE’s extended mission called NEOWISE that looked especially for Near Earth Object “Earth always is chasing this asteroid around.”

A handful of other asteroids also have orbits similar to Earth. Such objects could make excellent candidates for future robotic or human exploration. Asteroid 2010 TK7 is not a good target because it travels too far above and below the plane of Earth’s orbit, which would require large amounts of fuel to reach it.

“This observation illustrates why NASA’s NEO Observation program funded the mission enhancement to process data collected by WISE,” said Lindley Johnson, NEOWISE program executive at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “We believed there was great potential to find objects in near-Earth space that had not been seen before.”

The WISE telescope scanned the entire sky in infrared light from January 2010 to February 2011. The NEOWISE project observed more than 155,000 asteroids in the main belt between Mars and Jupiter, and more than 500 NEOs, discovering 132 that were previously unknown.

Sources: Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope, NASA

New Trojan Asteroid Discovered Around Neptune

[/caption]

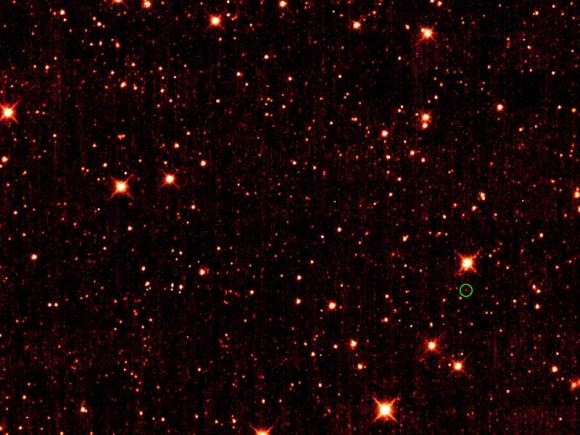

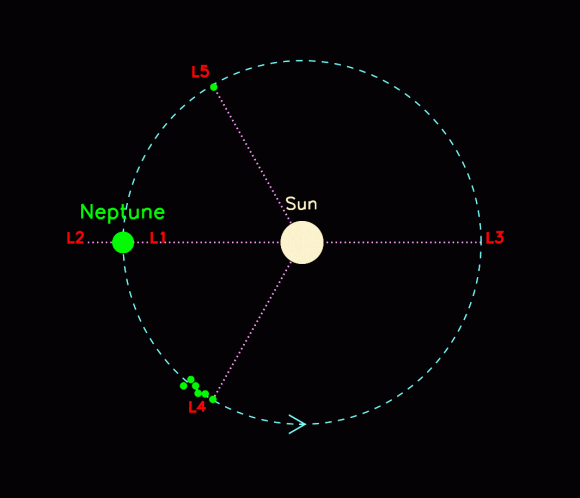

Astronomers have found a new object in a region of Neptune’s orbit, tucked away in a very hard-to-find location, and where no previous object was known to exist. The object, 2008 LC18, is a Trojan asteroid, which refers an asteroid that shares an orbit with a larger planet or moon, but does not collide with it because it orbits around one of the two Lagrangian points of stability. Six other Trojan asteroids have been located around Neptune’s L4 region, but this is the first one found in Neptune’s L5 region.

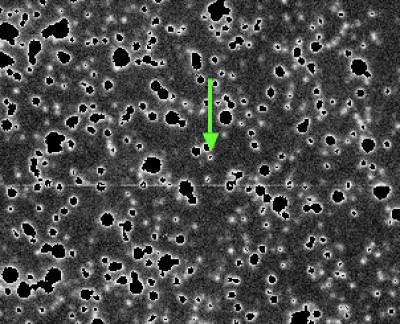

Scott Sheppard from the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Terrestrial Magnetism and colleagues used a new observational technique that used large dark clouds to block background light from the galactic plane in order to discover the new Neptune Trojan. They used the discovery to estimate the asteroid population there and find that it is probably similar to the asteroid population at Neptune’s L4 point.

“We estimate that the new Neptune Trojan has a diameter of about 100 kilometers and that there are about 150 Neptune Trojans of similar size at L5,” said Sheppard “It matches the population estimates for the L4 Neptune stability region. This makes the Neptune Trojans more numerous than those bodies in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. There are fewer Neptune Trojans known simply because they are very faint since they are so far from the Earth and Sun.”

Jupiter has the most Trojans, 4,076 (as of February 2010) but there are four known Mars Trojans and now seven known Neptune Trojans. So far, searches have failed to uncover any similar objects in the orbits of any other planets.

“The L4 and L5 Neptune Trojan stability regions lie about 60 degrees ahead of and behind the planet, respectively,” said Sheppard “Unlike the other three Lagrangian points, these two areas are particularly stable, so dust and other objects tend to collect there. We found 3 of the 6 known Neptune Trojans in the L4 region in the last several years, but L5 is very difficult to observe because the line-of-sight of the region is near the bright center of our galaxy.”

Sheppard and his team, which included Chad Trujillo from the Gemini Observatory, used images from a digitized all-sky survey to identify places in the stability regions where dust clouds in our galaxy blocked out the background starlight from the galaxy’s plane, providing an observational window to the foreground asteroids. They discovered the L5 Neptune Trojan using the 8.2-meter Japanese Subaru telescope in Hawaii and determined its orbit with Carnegie’s 6.5-meter Magellan telescopes at Las Campanas, Chile.

Because Trojans share their planet’s orbit they are sensitive to the planet’s formation and migration, and astronomers say finding these objects provide clues that may help unlock the answers to fundamental questions about planetary formation and migration.

The region of space is also of interest to the teams from the New Horizon spacecraft, as it will pass through this same area after its encounter with Pluto in 2015.

Sources: Carnegie Institute, Science Express.