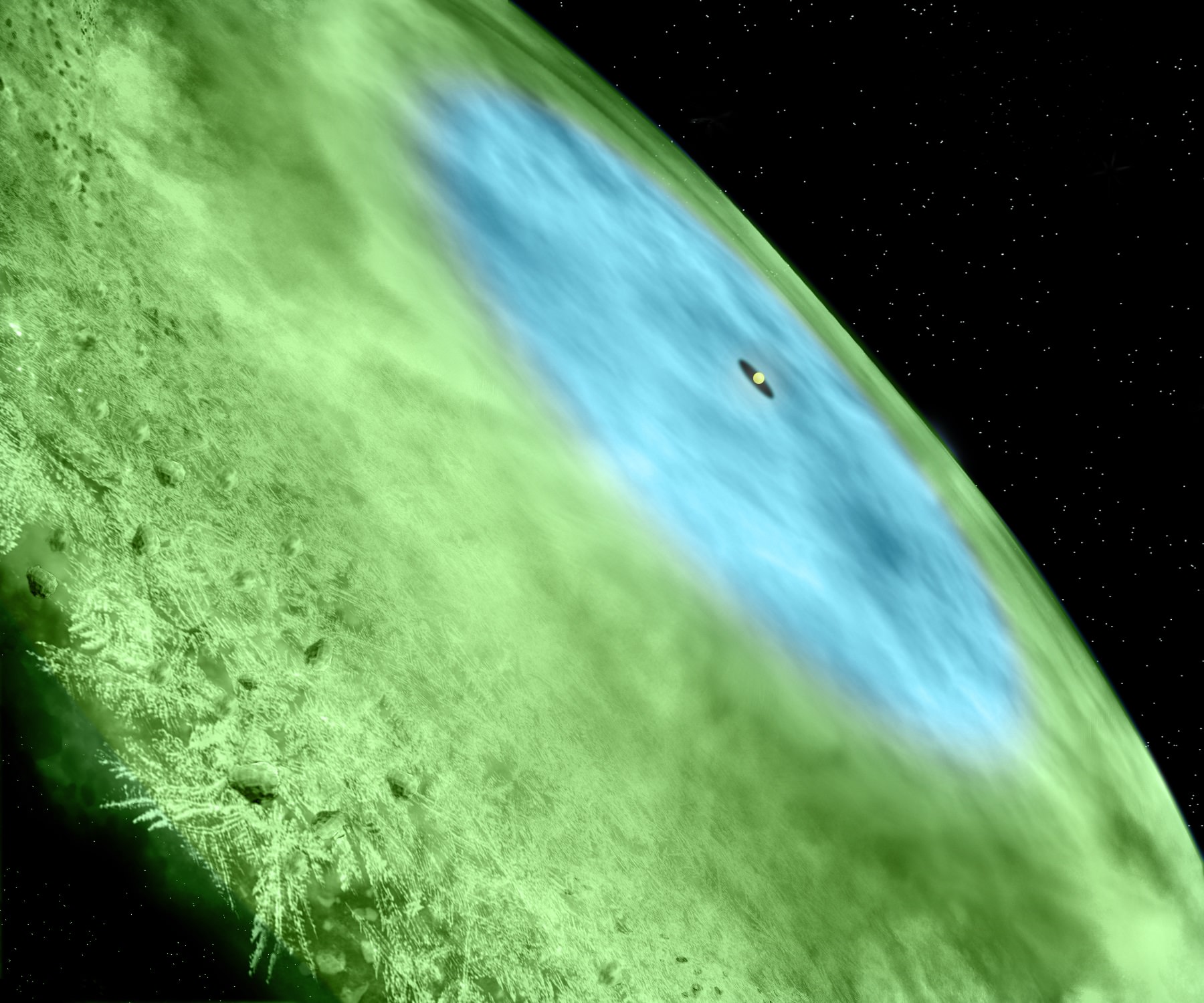

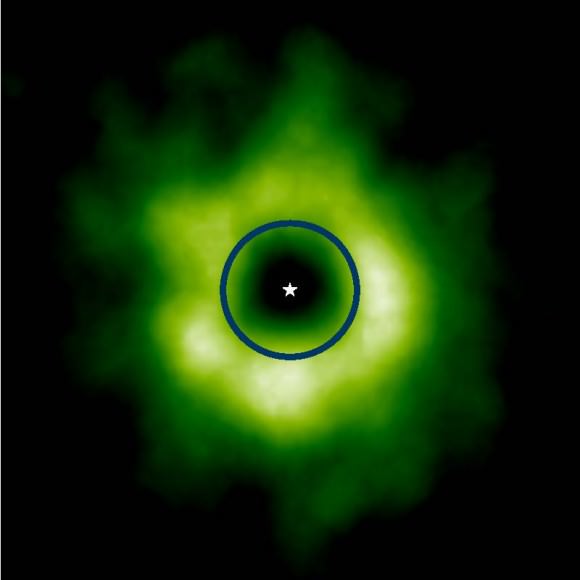

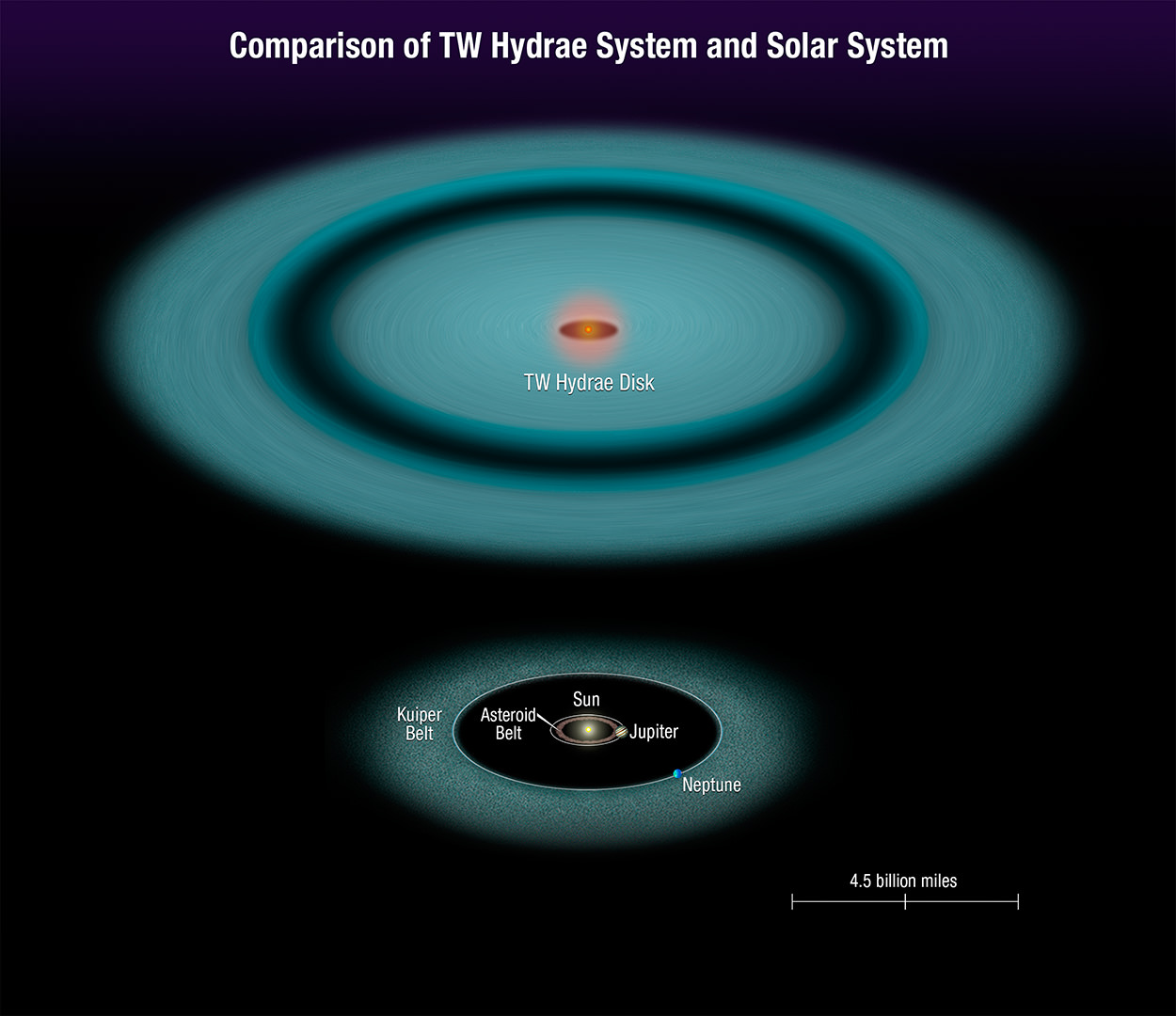

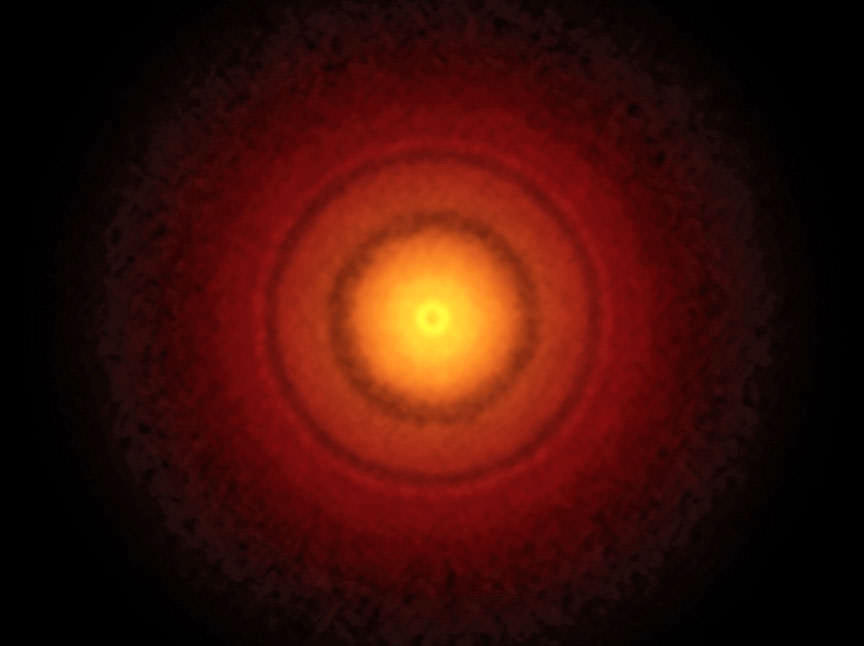

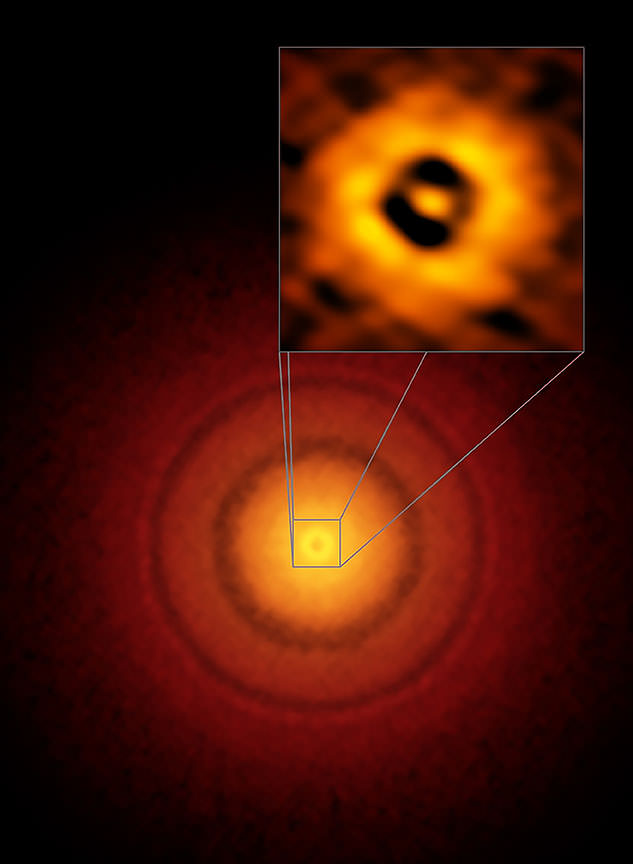

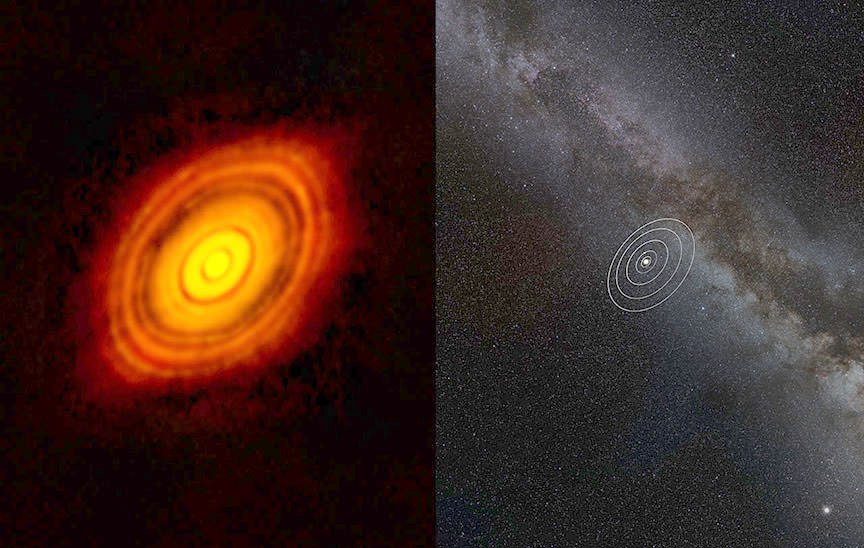

TW Hydrae is a special star. Located 175 light years from Earth in the constellation Hydra the Water Snake, it sits at the center of a dense disk of gas and dust that astronomers think resembles our solar system when it was just 10 million years old. The disk is incredibly clear in images made using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, which employs 66 radio telescopes sensitive to light just beyond that of infrared. Spread across more than 9 miles (15 kilometers), the ALMA array acts as a gigantic single telescope that can make images 10 times sharper than even the Hubble Space Telescope.

Astronomers everywhere point their telescopes at TW Hydrae because it’s the closest infant star in the sky. With an age of between 5 and 10 million years, it’s not even running on hydrogen fusion yet, the process by which stars convert hydrogen into helium to produce energy. TW Hydrae shines from the energy released as it contracts through gravity. Fusion and official stardom won’t begin until it’s dense enough and hot enough for fusion to fire up in its belly.

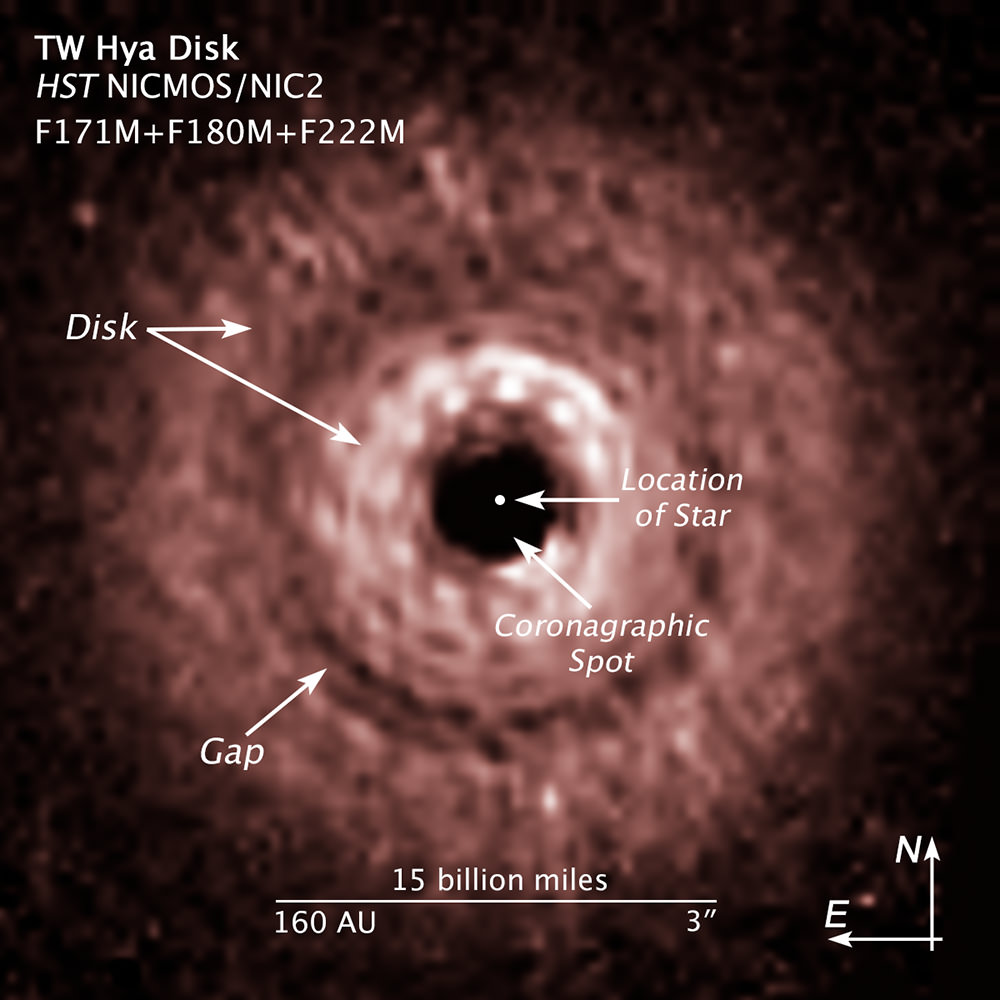

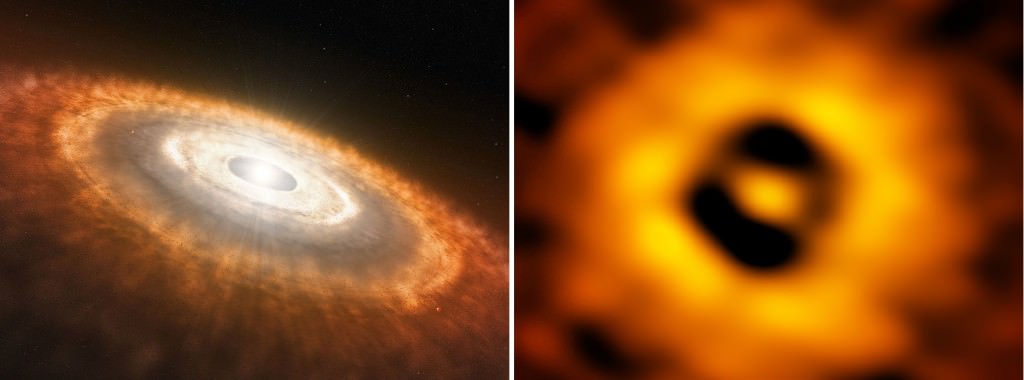

We see most protoplanetary disks at various angles, but TW’s has a face-on orientation as seen from Earth, giving astronomers a rare, undistorted view of the complete disk around the star. The new images show amazing detail, revealing a series of concentric bright rings of dust separated by dark gaps. There’s even indications that a planet with an Earth-like orbit has begun clearing an orbit.

“Previous studies with optical and radio telescopes confirm that TW Hydrae hosts a prominent disk with features that strongly suggest planets are beginning to coalesce,” said Sean Andrews with the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA and lead author on a paper published today in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Pronounced gaps that show up in the photos above are located at 1.9 and 3.7 billion miles (3-6 billion kilometers) from the central star, similar to the average distances from the sun to Uranus and Pluto in the solar system. They too are likely to be the results of particles that came together to form planets, which then swept their orbits clear of dust and gas to sculpt the remaining material into well-defined bands. ALMA picks up the faint emission of submillimeter light emitted by dust grains in the disk, revealing details as small as 93 million miles (150 million kilometers) or the distance of Earth from the sun

“This is the highest spatial resolution image ever of a protoplanetary disk from ALMA, and that won’t be easily beaten in the future!” said Andrews.

Earlier ALMA observations of another system, HL Tauri, show that even younger protoplanetary disks — a mere 1 million years old — look remarkably similar. By studying the older TW Hydrae disk, astronomers hope to better understand the evolution of our own planet and the prospects for similar systems throughout the Milky Way.