In a finding that could turn supermassive black hole formation theories upside-down, astronomers have spotted one of these beasts inside a tiny galaxy just 157 light-years across — about 500 times smaller than the Milky Way.

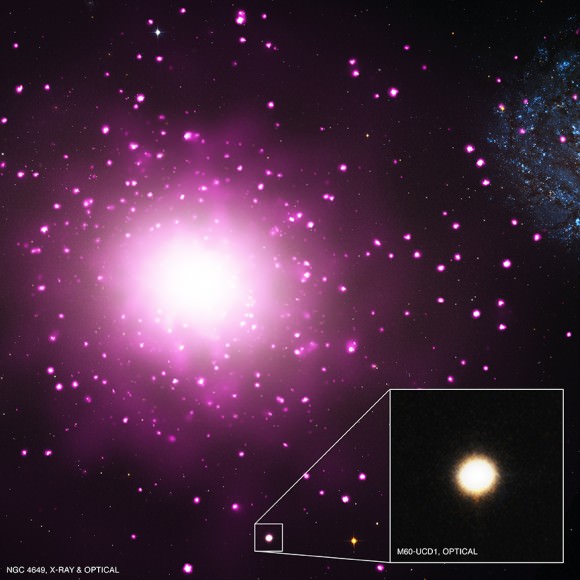

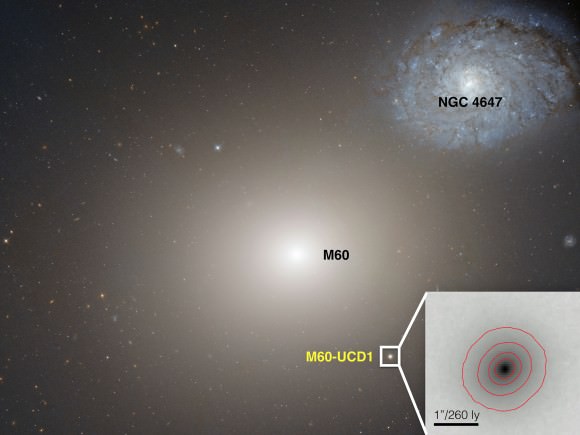

The clincher will be if the team can find more black holes like it, and that’s something they’re already starting to work on after the discovery inside of galaxy M60-UCD1. The ultracompact galaxy is one of only about 50 known to astronomers in the nearest galaxy clusters.

“It’s very much like a pinprick in the sky,” said lead researcher Anil Seth, an astrophysicist at the University of Utah, of M60-UCD1 during an online press briefing Tuesday (Sept. 16).

Seth said he realized something special was happening when he saw the plot for stellar motions inside of M60-UCD1, based on data from the Gemini North Telescope in Hawaii. The stars in the center of the galaxy were orbiting much more rapidly than those at the edge. The velocity was unexpected given the kind of stars that are in the galaxy.

“Immediately when I saw the stellar motions map, I knew we were seeing something exciting,” Seth said. “I knew pretty much right away there was an interesting result there.”

In its weight class, M60-UCD1 is a standout. Last year, Seth was second co-author on a group that announced that it was the densest nearby galaxy, with stars jam-packed 25 times closer than in the Milky Way. It’s also one of the brightest they know of, a fact that is helped by the galaxy’s relative closeness to Earth. It’s roughly 54 million light-years away, as is the massive galaxy it orbits: M60. The two galaxies are only 20,000 light-years apart.

Supermassive black holes are known to lurk in the centers of most larger galaxies, including the Milky Way. How they got there in the first place, however, is unclear. The find inside of M60-UCD1 is especially intriguing given the relative size of the black hole to the galaxy itself. The black hole is about 15% of the galaxy’s mass, with an equivalent mass of 21 million Suns. The Milky Way’s black hole, by contrast, takes up less than a percentage of our galaxy’s mass.

Given so few ultracompact galaxies are known to astronomers, some basic properties are a mystery. For example, the mass of these galaxy types tends to be higher than expected based on their starlight.

Some astronomers suggest it’s because they have more massive stars than other galaxy types, but Seth said measurements of stars within M60-UCD1 (based on their orbital motion) show normal masses. The extra mass instead comes from the black hole, he argues, and that will likely be true of other ultracompact galaxies as well.

“It’s a new place to look for black holes that was previously not recognized,” he said, but acknowledged the idea of black holes existing in similar galaxies will not be widely accepted until the team makes more finds. An alternative explanation to a black hole could be a suite of low-mass stars or neutron stars that do not give off a lot of light, but Seth said the number of these required in M60-UCD1 is “unreasonably high.”

His team plans to look at several other ultracompact galaxies such as M60-UCD1, but perhaps only seven to eight others would be bright enough from Earth to perform these measurements, he said. (Further work would likely require an instrument such as the forthcoming Thirty-Meter Telescope, he said.) Additionally, Seth has research interests in globular clusters — vast collections of stars — and plans a visit to Hawaii next month to search for black holes in these objects as well.

Results were published today (Sept. 17) in the journal Nature.