Wouldn’t it be easier to see what’s outside the solar system if we just send out probes straight up?

Dammit, science people! Why are you always firing probes “outwards”? Then they have to go past all this stuff, like planets and asteroids and crap to escape the solar system. Don’t you realize that if we want to see what’s outside the solar system we just need to shoot them straight up?

Then we don’t have to go past all that junk, and we can finally see what’s between us and the next star system over! Is it thick goo? Is it thin goo? Is it the aether?!

What the heck is wrong with you! It’s so easy. Just go up! Why are we always going out?

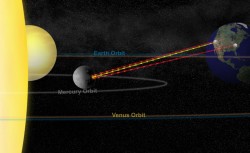

Whenever we talk Solar System, we’re always using flat objects for reference. Plates, flying disks, pancakes and pizzas, as it’s arranged in a flat disk known as the plane of the ecliptic.

Formed from a blob of hydrogen gas and dust in the solar nebula. Gravity pulled everything together, and the conservation of angular momentum set the whole thing spinning, faster and faster. The spinning pulled the whole Solar System into the disk we see today, with our star at the center and the planets embedded in the surrounding disk. As a result, the Sun, Moon, planets and their moons all move through a relatively small region in the sky.

This definitely makes things easier to send spacecraft from world to world. NASA’s Voyager 2 was able to visit Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune because they were all lined up like dominoes.

When Willie Sutton was asked why he robbed banks, he answered, “that’s where the money is,” and we explore along the plane of the ecliptic because that’s where the science is. Everything in our Solar System is arranged along this flat area, so it makes sense to look along this region.

But wait! As you know, the Solar System isn’t actually flat. Some objects rise a little above or below the plane of the ecliptic. This is known as a planet’s orbital inclination.

Of all the planets, Mercury has the greatest with 7-percent. It’s even crazier for the the dwarf planets, Pluto is 17-percent off the plane of the ecliptic, and Eris is 44-percent.

One of the reasons Eris went undiscovered for so long is because it orbits so far outside the planet of the ecliptic. It wasn’t until Mike Brown and his team from Caltech looked far enough outside the usual hiding spaces that they found these additional dwarf planets.

There really isn’t much outside the flat plane of the ecliptic, it’s also much more difficult to get spacecraft to travel above or below. When spacecraft launch, they already have tremendous velocity just from the rotation of the Earth and the speed of the Earth orbiting the Sun.

I realize this is just more “outwardist” propaganda for you. So why no “up”? If you did want to go that way, you need a powerful rocket capable of creating velocity in this direction, or that direction.

If you wanted to escape the Earth’s gravity and explore the Solar System in the regular old way, you’d need to add about 10 km/s in velocity to your spacecraft. But for straight up, you’d need about 30 km/s, meaning more fuel, and compromises to your payload.

It still sounds like I’m making excuses. Here’s the deal, you might be amazed to learn that spacecraft actually have been sent “up”.

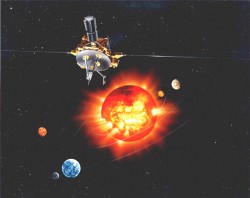

The European Space Agency’s Ulysses spacecraft, launched in 1990 had the goal of looking down on the Sun from above. It wasn’t possible to do this just with a rocket, but engineers were able to use a gravitational assist from Jupiter to kick Ulysses into an orbital inclination of 80-degrees, and for the first time, we were able to see the Sun from above and below.

A new European mission is in the works called the Solar Orbiter, and it’ll get into an orbital inclination of 90-degrees to be able to see the Sun’s poles directly for the first time. If all goes well, it’ll launch in 2018.

So, why don’t we go up? Actually, we do. We’re going “up” again very soon. It’s good to go up. It’s always good to get outside of our regular stomping grounds and see our Solar System from new angles and perspectives.

If you could send a probe anywhere in our Solar System, where would you choose?