What color is the Universe? Turns out this isn’t a simple question, and one that scientists have really been unable to answer, until now!

Continue reading “Astronomy Cast Ep. 412: The Color of the Universe”

What’s Outside the Universe?

A few hundred episodes ago, I answered the question, “What is the Universe Expanding Into?” The gist of the answer is that the Universe as we understand it, isn’t really expanding into anything.

If you go in any one direction long enough, you just return to your starting point. As the Universe expands, that journey takes longer, but there’s still nothing that it’s going into.

Okay, so, I need to put an asterisk on that answer, and then when you read the fine print it’d say something like, “unless we live in a multiverse”.

One of the super interesting and definitely way out there ideas is that our cosmos to actually just one universe in a vast multiverse. Each universe is sort of like a soap bubble embedded in the cosmic void of the multiverse, expanding from its own Big Bang.

And in each one of these universes, the laws of physics are completely different. There are actually a bunch of physical constants in the Universe, like the force of gravity or the binding strength of atoms. For each one of those basic constants, it’s as if the laws of physics randomly rolled the dice, and came up with our Universe – a place that’s almost, but not completely hostile to life.

So imagine all these different bubble universes popping up in this vast cosmic foam of the multiverse, and the laws of physics are different. Maybe in another universe, the force of gravity is repulsive, or green, or spawns unicorns.

In the vast majority of those universes, no life could ever form, but roll the dice an infinite number of times and you’ll eventually get the conditions for life.

Any lifeform capable of perceiving the Universe had to evolve into a universe capable of life.

Of course, this sounds like pseudo scientific mumbo jumbo, and next you’ll expect me to talk about chakras, astrology and channeling the spirit of Big Foot.

However, hang on a second, this might actually be science. If these bubble universes got close enough, there might be a way they could rub together, to interact in ways that were detectable from within the Universe.

In other words, we could look out into space and see a cosmic bruise, and know that’s where our universe is colliding with another one.

Well, have astronomers looked out into space, in search of some sign that our Universe is interacting with other universes? Indeed they have, and they’ve found something really strange.

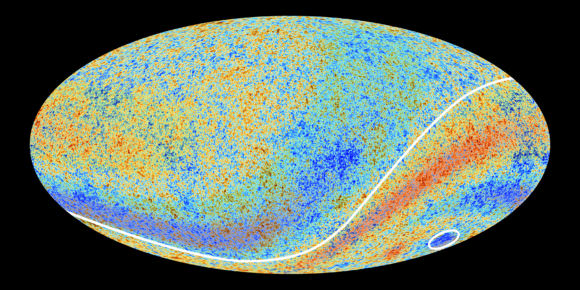

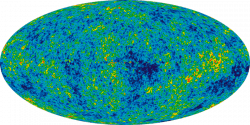

When examining the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation, the afterglow leftover from the Big Bang, astronomers have found a temperature fluctuations. These different temperatures, or anisotropies are regions where different densities of matter in the early Universe were scaled up to enormous scales by the ongoing expansion.

While most of these differences in temperature are explained by the current cosmological theories for the Universe, there’s one region that defies the theories. It’s so strange, the researchers who discovered it hilariously named it the “Axis of Evil” after something some president said.

Anyway, there are lots of ideas for what the Axis of Evil might be. Seriously, every single one of them is more reasonable and more likely than what I’m about to say.

But one really fascinating idea is that we’re seeing a region where our Universe is bumping into another universe, violating each other’s laws of physics.

So if this is the case, and astronomers are witnessing a universal interaction, what does this mean for the poor aliens who might be getting overlapped by the next universe over?

We have no idea, but imagine what might happen as the laws of physics from two completely different universes overlap. What is the average of 7 and green? Or 26 and unicorn dreams? Whatever it is, it can’t be good for the aliens and their continued healthy existence.

But don’t worry, that region is billions of light years away, and it’s probably not another universe anyway, we just need better observations.

We covered this topic in great detail in episode 408 of Astronomy Cast, so if you want hear more from Dr. Pamela Gay, click here and watch the show. You’ll especially enjoy watching me pick up the shattered pieces of my brain as I try to wrap my head around this mind bending concept.

Do We Live in a Special Part of the Universe?

We’ve already talked about how you’re living at the center of the Universe. Now, I’m not going to say that the whole Universe revolves around you… but we both know it does. So does this mean that there’s something special about where we live? This is a reasonable line of thinking, and it was how modern science got its start. The first astronomers assumed that the Sun, Moon, planets and stars orbited around the Earth. That the Earth was a very special and unique place, distinct from the rest of the Universe. But as astronomers started puzzling out the nature of the laws of physics, they realized that the Earth wasn’t as special as they thought. In fact, the laws of nature that govern the forces on Earth are the same everywhere in the Universe. As Isaac Newton untangled the laws of gravity here on Earth, he realized it must be the same forces that caused the Moon to go around the Earth, and the planets to go around the Sun. That the light from the Sun is the same phenomenon as the light from other stars.

When astronomers consider the Universe at the largest scales, they assume that it’s homogeneous, and isotropic. Technical words, I know, so here’s what they mean. When astronomers say the Universe is homogeneous, this means that observers in any part of the Universe will see roughly the same view as observers in any other part. There might be local differences, like our mostly harmless planet Earth, orbiting the future course of an interstellar bypass. Or a desert planet with two suns, or a swampy world in the Dagobah system. At the smallest scales, they’ll be different. But as you move to larger and larger scales, it’s all just planets, stars, galaxies, galaxy clusters and black holes. And if you unfocus your eyes, it all looks pretty much the same. Isotropic means that the Universe looks the same in every direction. If you were floating alone in the cosmic void, you could look left, right, up, down out to the edge of the observable Universe and see galaxies, galaxy clusters and eventually the cosmic microwave background radiation in all directions. Every direction looks the same. This is know as the cosmological principle, and it’s one of the foundations of astronomy, because it means that we have a chance at understanding the physical laws of the Universe. If the Universe wasn’t homogeneous and isotropic, then it would mean that the physical laws as we understand them are impossible to comprehend. Just over the cosmological horizon, the force of gravity might act in reverse, the speed of light might be slower than walking speed, and unicorns could be real. That could be true, but we have to assume it’s not. And our current observations, at least to a sphere 13.8 billion light years around us in all directions, confirm this.

While we don’t live in a special place in the Universe, we do live in a special time in the Universe. In the distant future, billions or even trillions of years from now, galaxies will be flying away from us so quickly that their light will never reach us. The cosmic background microwave radiation will be redshifted so far that it’s completely undetectable. Future astronomers will have no idea that there was ever a greater cosmology beyond the Milky Way itself. The evidence of the Big Bang and the ongoing expansion of the Universe will be lost forever. If we didn’t happen to live when we do now, within billions of years of the beginning of the Universe, we’d never know the truth. We can’t feel special about our place in the Universe, it’s probably the same wherever you go. But we can feel special about our time in the Universe. Future astronomers will never understand the cosmology and history of the cosmos the way we do now.

Astronomy Cast Ep. 408: Universe Cannibalism

We’ve talked about stellar cannibalism and galactic cannibalism, but now it’s time to take this concept to its logical extreme – universe cannibalism. In the multiverse theory of physics we live in just one of a vast range of universes which might interact with each other. Let’s look for the evidence.

Continue reading “Astronomy Cast Ep. 408: Universe Cannibalism”

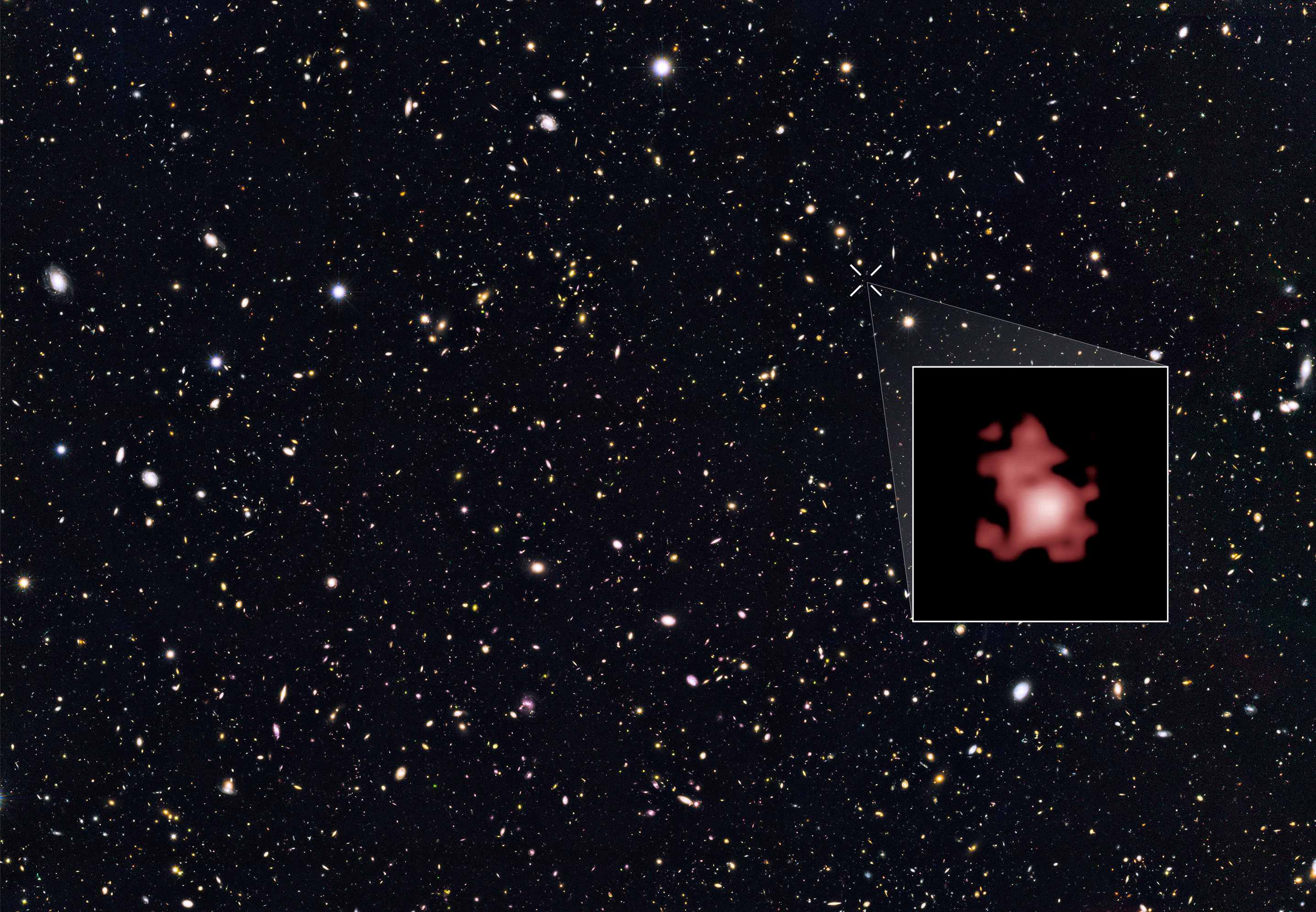

Farthest Galaxy Ever Seen Viewed By Hubble Telescope

Since it was first launched in 1990, the Hubble Space Telescope has provided people all over the world with breathtaking views of the Universe. Using its high-tech suite of instruments, Hubble has helped resolve some long-standing problems in astronomy, and helped to raise new questions. And always, its operators have been pushing it to the limit, hoping to gaze farther and farther into the great beyond and see what’s lurking there.

And as NASA announced with a recent press release, using the HST, an international team of astronomers just shattered the cosmic distance record by measuring the farthest galaxy ever seen in the universe. In so doing, they have not only looked deeper into the cosmos than ever before, but deeper into it’s past. And what they have seen could tell us much about the early Universe and its formation.

Due to the effects of special relativity, astronomers know that when they are viewing objects in deep space, they are seeing them as they were millions or even billions of years ago. Ergo, an objects that is located 13.4 billions of light-years away will appear to us as it was 13.4 billion years ago, when its light first began to make the trip to our little corner of the Universe.

This is precisely what the team of astronomers witnessed when they gazed upon GN-z11, a distant galaxy located in the direction of the constellation of Ursa Major. With this one galaxy, the team of astronomers – which includes scientists from Yale University, the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), and the University of California – were able to see what a galaxy in our Universe looked like just 400 million years after the Big Bang.

Prior to this, the most distant galaxy ever viewed by astronomers was located 13.2 billion light years away. Using the same spectroscopic techniques, the Hubble team confirmed that GN-z11 was nearly 200 million light years more distant. This was a big surprise, as it took astronomers into a region of the Universe that was thought to be unreachable using the Hubble Space Telescope.

In fact, astronomers did not suspect that they would be able to probe this deep into space and time without using Spitzer, or until the deployment the James Webb Space Telescope – which is scheduled to launch in October 2018. As Pascal Oesch of Yale University, the principal investigator of the study, explained:

“We’ve taken a major step back in time, beyond what we’d ever expected to be able to do with Hubble. We see GN-z11 at a time when the universe was only three percent of its current age. Hubble and Spitzer are already reaching into Webb territory.”

In addition, the findings also have some implications for previous distance estimates. In the past, astronomers had estimated the distance of GN-z11 by relying on Hubble and Spitzer’s color imaging techniques. This time, they relied on Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 to spectroscopically measure the galaxies redshift for the first time. In so doing, they determined that GN-z11 was farther way than they thought, which could mean that some particularly bright galaxies who’s distanced have been measured using Hubble could also be farther away.

The results also reveal surprising new clues about the nature of the very early universe. For starters, the Hubble images (combined with data from Spitzer) showed that GN-z11 is 25 times smaller than the Milky Way is today, and has just one percent of our galaxy’s mass in stars. At the same time, it is forming stars at a rate that is 20 times greater than that of our own galaxy.

As Garth Illingworth – one of the team’s investigator’s from the University of California, Santa Cruz – explained:

“It’s amazing that a galaxy so massive existed only 200 million to 300 million years after the very first stars started to form. It takes really fast growth, producing stars at a huge rate, to have formed a galaxy that is a billion solar masses so soon. This new record will likely stand until the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope.”

Last, but not least, they provide a tantalizing clue as to what future missions – like the James Webb Space Telescope – will be finding. Once deployed, astronomers will likely be looking ever farther into space, and farther into the past. With every step, we are closing in on seeing what the very first galaxies that formed in our Universe looked like.

Further Reading: NASA

Our Place in the Universe: The Most Detailed Map Yet

Astronomy and the other space sciences are the best branches of science for pure eye candy. Biology is great, but who wants to watch videos of a cell dividing? Over and over again. Not me, and not you either, I’ll bet.

This new video from Futurism.com shows our place in the Laniakea Supercluster. Superclusters are the largest-scale structures in the universe, and next to them, we are indeed puny creatures. Our Milky Way galaxy is but a tiny dot in an unremarkable corner of Laniakea.

Thanks to Futurism.com, Nature.com, and R. Brent Tully at the University of Hawaii, we can see better than ever how we Milky Way inhabitants fit into the larger structure of the Universe.

This video is actually a spiffy new edit of an older video, with explanatory voice-over. Check it out.

Is the Universe Perfect for Life?

Doesn’t it feel like the Universe is perfectly tuned for life? Actually, it’s a horrible hostile place, delivering the bare minimum for human survival.

Consider that incomprehensible series of events that brought you to this moment. In a way that we still don’t understand, a complex mix of chemicals came together in just the right combination to kick off the evolution of life.

Generation after generation of bacteria, insects, fish, lizards, mammals and eventually humans somehow successfully found a buddy and passed along their genetic material to another generation. Clever humans invented computers, the internet, YouTube, and somehow you found your way to this exact video, to hear these words. Whoa.

It’s amazing to consider the Universe we live in, and how it’s perfectly tuned for life. If just a single variable was a little bit different, life as we know it probably wouldn’t exist. Gravity might be a repulsive force. Pokemons might catch you.

Doesn’t it feel like the Universe was created especially for us? I mean, didn’t I already tell you that we’re all the center of the Universe?

I’m sad to say, but this couldn’t be further from the truth. The reality is that the Universe is 100% completely inhospitable. Well, apart from a thin layer on the surface of our Earth, but that’s got to be a rounding error. A fraction of a fraction of a fraction of the teeniest percent of the volume of the Universe. The rest of the Universe is bunk.

If I was plucked out of our cozy environment and dropped into the near vacuum of pretty much anywhere else, the only resource would be a handful of hydrogen atoms. And what can you do with a few hydrogen atoms? Nothing. It might even give Bear Grylls a run for his money. He might have a little more trouble on a star’s surface, crisping up in a heartbeat.

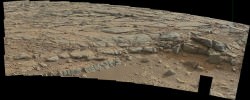

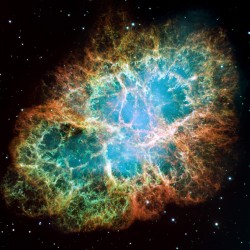

Into a black hole? Surface of a neutron star? Near an exploding supernova? Please enjoy the crushing pressures and hellish temperatures of Venus, or the freezing irradiated surface of Mars.

Earth itself is mostly a deathtrap. Travel down a few kilometers and you’d bake and crush from the rising temperatures of the Earth’s interior. Travel up and the air gets thin, cold and killy. In fact, without our technology heating, cooling, or helping us breathe, we wouldn’t last more than a few days on most of the planet.

When you think about the landscape of time, we even live in a brief thumbnail of a moment when Earth is hospitable. Over the next few billion years, the Sun is going to heat up to the point that the surface of Earth will resemble the surface of Venus. And then the last hospitable hidey-hole in the entire Universe, that we know of, will wink out. The Universe is as inhospitable as it could possibly be. That is, without being completely inhospitable.

Especially when you consider the timeframes, and the long future when all the stars have died, where there’s nothing but black holes and frozen matter, and the Universe finally ditches that rounding error, and becomes 100% purely inhospitable.

Cosmologists use a term known as the anthropic principle to explain this very special moment we find ourselves in. There’s the greater anthropic principle that says the Universe wouldn’t be here without us to observe it, but that seems nutty and egotistical.

The lesser anthropic principle says that if the Universe turned out any differently, we wouldn’t be here to observe it.

Imagine you threw a dart out the window of an airplane and it landed in a tiny spot on the surface of the Earth. What were the chances that it would land there? Almost zero. What a lucky spot.

You can imagine all kinds of other even more inhospitable Universes, where the conditions were never good enough for life to evolve, and so intelligent civilizations could never even ask the question, “Is Our Universe Perfect for Life.”

So when you look out across a meadow in the springtime. The birds are chirping, and there’s new growth everywhere, don’t forget about the boiling rock magma beneath your feet, the frigid air and then vacuum above your head, and the whole Universe of burning, radiating, impacting objects trying their best to kill you.

Of all the extreme environments in the Universe, which ones do you find most fascinating? Tell us in the comments below.

How Are Galaxies Moving Away Faster Than Light?

So, how can galaxies be traveling faster than the speed of light when nothing can travel faster than light?

I’m a little world of contradictions. “Not even light itself can escape a black hole”, and then, “black holes and they are the brightest objects in the Universe”. I’ve also said “nothing can travel faster than the speed of light”. And then I’ll say something like, “ galaxies are moving away from us faster than the speed of light.” There’s more than a few items on this list, and it’s confusing at best. Thanks Universe!

So, how can galaxies be traveling faster than the speed of light when nothing can travel faster than light? Warp speed galaxies come up when I talk about the expansion of the Universe. Perhaps it’s dark energy acceleration, or the earliest inflationary period of the Universe when EVERYTHING expanded faster than the speed of light.

Imagine our expanding Universe. It’s not an explosion from a specific place, with galaxies hurtling out like cosmic jetsam. It’s an expansion of space. There’s no center, and the Universe isn’t expanding into anything.

I’d suggested that this is a terribly oversimplified model for our Universe expanding. Unfortunately, it’s also terribly convenient. I can steal it from my children whenever I want.

Imagine you’re this node here, and as the toy expands, you see all these other nodes moving away from you. And if you were to move to any other node, you’d see all the other nodes moving away from you.

Here’s the interesting part, these nodes over here, twice as far away as the closer ones, appear to move more quickly away from you. The further out the node is, the faster it appears to be moving away from you.

This is our freaky friend, the Hubble Constant, the idea that for every megaparsec of distance between us and a distant galaxy, the speed separating them increases by about 71 kilometers per second.

Galaxies separated by 2 parsecs will increase their speed by 142 kilometers every second. If you run the mathatron, once you get out to 4,200 megaparsecs away, two galaxies will see each other traveling away faster than the speed of light. How big Is that, is it larger than the Universe?

The first light ever, the cosmic microwave background radiation, is 46 billion light-years away from us in all directions. I did the math and 4,200 megaparsecs is a little over 13.7 billion light-years.There’s mountains of room for objects to be more than 4,200 megaparsecs away from each other. Thanks Universe?!?

Most of the Universe we can see is already racing away at faster than the speed of light. So how it’s possible to see the light from any galaxies moving faster than the speed of light. How can we even see the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation? Thanks Universe.

Light emitted by the galaxies is moving towards us, while the galaxy itself is traveling away from us, so the photons emitted by all the stars can still reach us. These wavelengths of light get all stretched out, and duckslide further into the red end of the spectrum, off to infrared, microwave, and even radio waves. Given time, the photons will be stretched so far that we won’t be able to detect the galaxy at all.

In the distant future, all galaxies and radiation we see today will have faded away to be completely undetectable. Future astronomers will have no idea that there was ever a Big Bang, or that there are other galaxies outside the Milky Way. Thanks Universe.

I stand with Einstein when I say that nothing can move faster than light through space, but objects embedded in space can appear to expand faster than the speed of light depending on your perspective.

What aspects about cosmology still give you headaches? Give us some ideas for topics in the comments below.

Is the Universe Dying?

Is our 13.8 billion year old universe actually in its death throes?

Poor Universe, its demise announced right in it’s prime. At only 13.8 billion years old, when you peer across the multiverse it’s barely middle age. And yet, it sadly dwindles here in hospice.

Is it a Galactus infestation? The Unicronabetes? Time to let go, move on and find a new Universe, because this one is all but dead and gone and but a shell of its former self.

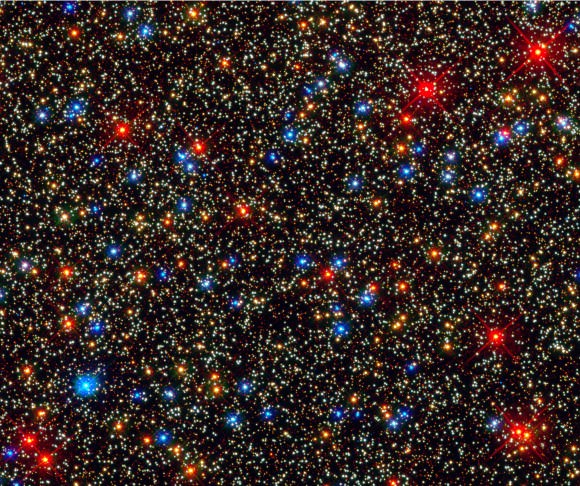

The news of imminent demise was recently broadcast in mid 2015. Based on research looking at the light coming from over 200,000 galaxies, they found that the galaxies are putting out half as much light as they were 2 billion years ago. So if our math is right, less light equals more death.

So tell it to me straight, Doctor Spaceman(SPAH-CHEM-AN), how long have we got? Astronomers have known for a long time that the Universe was much more active in the distant past, when everything was closer and denser, and better. Back then, more of it was the primordial hydrogen left over from the Big Bang, supplying galaxies for star formation. Currently, there are only 1 to 3 new stars formed in the Milky Way every year. Which is pretty slow by Milky Way standards.

Not even at the busiest time of star formation, our Sun formed 5 billion years ago. 5 billion years before that, just a short 4 billion after the Big Bang, star formation peaked out. There were 30 times more stars forming then, than we see today.

When stars were formed actually makes a difference. For example, the fact that it took so long for our Sun to form is a good thing. The heavier elements in the Solar System, really anything higher up the periodic table from hydrogen and helium, had to be formed inside other stars. Main sequence stars like our own Sun spew out heavier elements from their solar winds, while supernovae created the heaviest elements in a moment of catastrophic collapse. Astronomers are pretty sure we needed a few generations of stars to build up enough of the heavier elements that life depends on, and probably wouldn’t be here without it.

Even if life did form here on Earth billions of years ago, when the Universe was really cranking, it would wish it was never born. With 30 times as much star formation going on, there would be intense radiation blasting away from all these newly forming stars and their subsequent supernovae detonations. So be glad life formed when it did. Sometimes a little quiet is better.

So, how long has the Universe got? It appears that it’s not going to crash together in the future, it’s just going to keep on expanding, and expanding, forever and ever.

In a few billion years, star formation will be a fraction of what it is today. In a few trillion, only the longest lived, lowest mass red dwarfs will still be pushing out their feeble light. Then, one by one, galaxies will see their last star flicker and fade away into the darkness. Then there’ll only be dead stars and dead planets, cooling down to the background temperature of the Universe as their galaxies accelerate from one another into the expanding void.

Eventually everything will be black holes, or milling about waiting to be trapped in black holes. And these black holes themselves will take an incomprehensible mighty pile of years to evaporate away to nothing.

So yes, our Universe is dying. Just like in a cheery Sartre play, it started dying the moment it began its existence. According to astronomers, the Universe will never truly die. It’ll just reach a distant future when there’s so little usable energy, it’ll be mostly dead. Dead enough? Dead inside.

As Miracle Max knows, mostly dead is still slightly alive. Who knows what future civilizations will figure out in the googol years between then and now.

Too sad? Let’s wildly speculate on futuristic technologies advanced civilizations will use to outlast the heat death of the Universe or flat out cheat death and re-spark it into a whole new cycle of Universal renewal.

Our Universe is Dying

Brace yourselves: winter is coming. And by winter I mean the slow heat-death of the Universe, and by brace yourselves I mean don’t get terribly concerned because the process will take a very, very, very long time. (But still, it’s coming.)

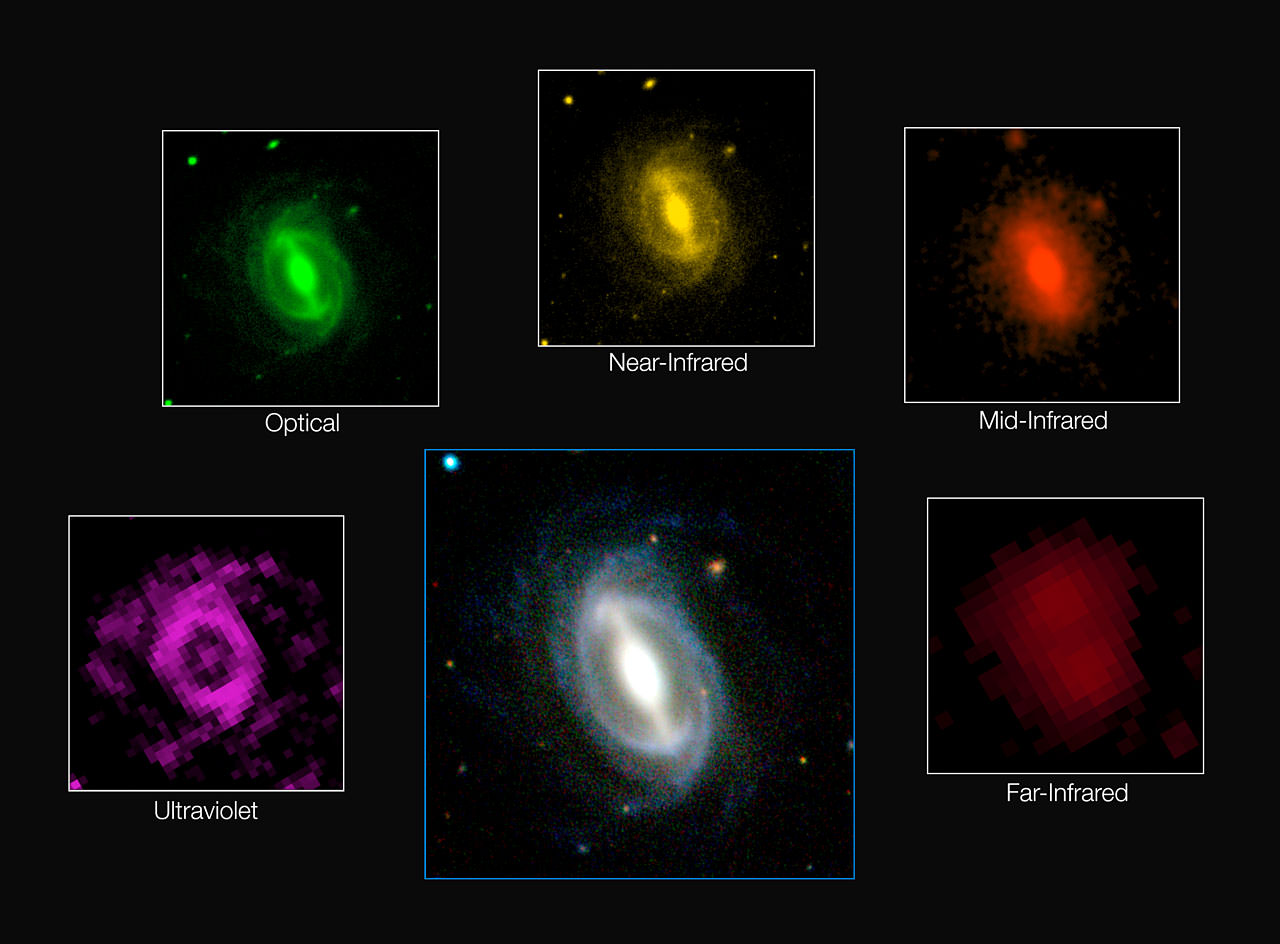

Based on findings from the Galaxy and Mass Assembly (GAMA) project, which used seven of the world’s most powerful telescopes to observe the sky in a wide array of electromagnetic wavelengths, the energy output of the nearby Universe (currently estimated to be ~13.82 billion years old) is currently half of what it was “only” 2 billion years ago — and it’s still decreasing.

“The Universe has basically plonked itself down on the sofa, pulled up a blanket and is about to nod off for an eternal doze,” said Professor Simon Driver from the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) in Western Australia, head of the nearly 100-member international research team.

As part of the GAMA survey 200,000 galaxies were observed in 21 different wavelengths, from ultraviolet to far-infrared, from both the ground and in space. It’s the largest multi-wavelength galaxy survey ever made.

Of course this is something scientists have known about for decades but what the survey shows is that the reduction in output is occurring across a wide range of wavelengths. The cooling is, on the whole, epidemic.

Watch a video below showing a fly-through 3D simulation of the GAMA survey:

“Just as we become less active in our old age, the same is happening with the Universe, and it’s well past its prime,” says Dr. Luke Davies, a member of the ICRAR research team, in the video.

But, unlike living carbon-based bags of mostly water like us, the Universe won’t ever actually die. And for a long time still galaxies will evolve, stars and planets will form, and life – wherever it may be found – will go on. But around it all the trend will be an inevitable dissipation of energy.

“It will just grow old forever, slowly converting less and less mass into energy as billions of years pass by,” Davies says, “until eventually it will become a cold, dark, and desolate place where all of the lights go out.”

Our own Solar System will be a quite different place by then, the Sun having cast off its outer layers – roasting Earth and the inner planets in the process – and spending its permanent retirement cooling off as a white dwarf. What will remain of Earthly organisms by then, including us? Will we have spread throughout the galaxy, bringing our planet’s evolutionary heritage with us to thrive elsewhere? Or will our cradle also be our grave? That’s entirely up to us. But one thing is certain: the Universe isn’t waiting around for us to decide what to do.

The findings were presented by Professor Driver on Aug. 10, 2015, at the IAU XXIX General Assembly in Honolulu, and have been submitted for publication in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.