It’s a case of mistaken identity: a near-Earth asteroid with a peculiar orbit turns out not to be an asteroid at all, but a comet… and not some Sun-dried burnt-out briquette either but an actual active comet containing rock and dust as well as CO2 and water ice. The discovery not only realizes the true nature of one particular NEO but could also shed new light on the origins of water here on Earth.

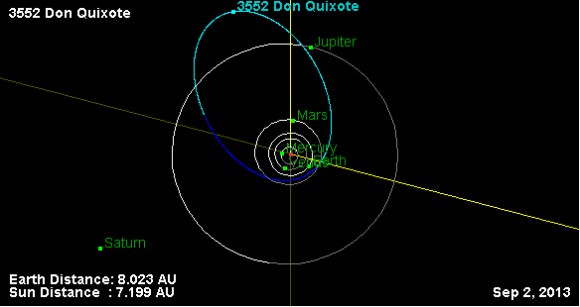

Designated 3552 Don Quixote, the 19-km-wide object is the third largest near-Earth object — mostly rocky asteroids that orbit the Sun in the vicinity of Earth.

According to the IAU, an asteroid is coined a near-Earth object (NEO) when its trajectory brings it within 1.3 AU from the Sun and within 0.3 AU of Earth’s orbit.

About 5 percent of near-Earth asteroids are thought to actually be dead comets. Today an international team including Joshua Emery, assistant professor of earth and planetary sciences at the University of Tennessee, have announced that Don Quixote is neither.

“Don Quixote has always been recognized as an oddball,” said Emery. “Its orbit brings it close to Earth, but also takes it way out past Jupiter. Such a vast orbit is similar to a comet’s, not an asteroid’s, which tend to be more circular — so people thought it was one that had shed all its ice deposits.”

Read more: 3552 Don Quixote… Leaving Our Solar System?

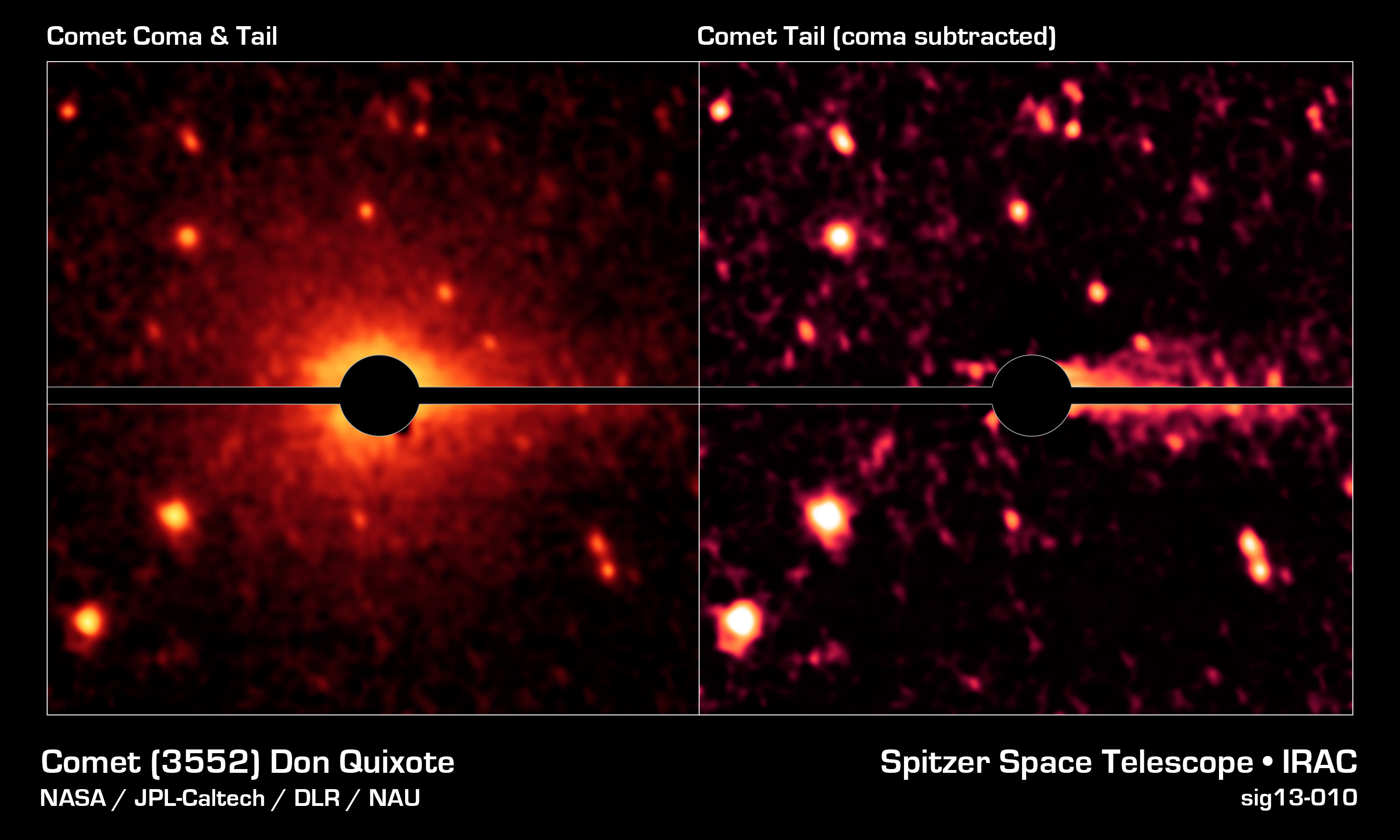

Using the NASA/JPL Spitzer Space Telescope, the team — led by Michael Mommert of Northern Arizona University — reexamined images of Don Quixote from 2009 when it was at perihelion and found it had a coma and a faint tail.

Emery also reexamined images from 2004, when Quixote was at its farthest distance from the Sun, and determined that the surface is composed of silicate dust, which is similar to comet dust. He also determined that Don Quixote did not have a coma or tail at this distance, which is common for comets because they need the sun’s radiation to form the coma and the sun’s charged particles to form the tail.

The researchers also confirmed Don Quixote’s size and the low, comet-like reflectivity of its surface.

“The power of the Spitzer telescope allowed us to spot the coma and tail, which was not possible using optical telescopes on the ground,” said Emery. “We now think this body contains a lot of ice, including carbon dioxide and/or carbon monoxide ice, rather than just being rocky.”

This discovery implies that carbon dioxide and water ice might be present within other near-Earth asteroids and may also have implications for the origins of water on Earth, as comets are thought to be the source of at least some of it.

The amount of water on Don Quixote is estimated to be about 100 billion tons — roughly the same amount in Lake Tahoe.

“Our observations clearly show the presence of a coma and a tail which we identify as molecular line emission from CO2 and thermal emission from dust. Our discovery indicates that more NEOs may harbor volatiles than previously expected.”

– Mommert et al., “Cometary Activity in Near–Earth Asteroid (3552) Don Quixote “

The findings were presented Sept. 10 at the European Planetary Science Congress 2013 in London.

Source: University of Tennessee press release

__________________

3552 Quixote isn’t the only asteroid found to exhibit comet-like behavior either — check out Elizabeth Howell’s recent article, “Asteroid vs. Comet: What the Heck is 3200 Phaethon?” for a look at another NEA with cometary aspirations.