[/caption]

Editor’s note: We all want to explore other worlds in our solar system, but perhaps you haven’t considered the bizarre weather you’d encounter — from the blistering hurricane-force winds of Venus to the gentle methane rain showers of Saturn’s giant moon Titan. Science journalist Michael Carroll has written a guest post for Universe Today which provides peek at the subject matter for his new book, “Drifting on Alien Winds: Exploring the Skies and Weather of Other Worlds.”

It’s been a dramatic year for weather on Earth. Blizzards have blanketed the east coast, crippling traffic and power grids. Cyclone Tasha drenched Queensland, Australia as rainfall swelled the mighty Mississippi, flooding the southern US. Eastern Europe and Asia broke high temperature records. But despite these meteorological theatrics, the Earth’s conditions are a calm echo of the weather on other worlds in our solar system.

Take our nearest planetary neighbor, Venus. Nearly a twin of Earth in size, Venus displays truly alien weather. The hurricane-force Venusian winds are ruled not by water (as on Earth), but by battery acid. Sunlight tears carbon dioxide molecules (CO2) apart in a process called photodissociation. Leftover bits of molecules frantically try to combine with sulfur and water to become chemically stable, resulting acid hazes. Temperatures soar to 900ºF at the surface, where air is as dense as the Earthly oceans at a depth of X feet.

Venus is the poster child of comparative planetology, the study of other planets to help us understand our own. Earth’s simmering sibling has taught us about greenhouse gases, and gave us an even more immediate cautionary tale in 1978. The Pioneer Venus orbiter discovered that Venus naturally generates chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) in its atmosphere. These CFCs were tearing holes in the planet’s ozone. At the same time, a wide variety of industries were preparing to use CFCs in insecticides, spray paints, and other aerosol products. Venus presented us with a warning that may have averted a planet-wide crisis.

In the same way, Mars has provided insights into long-term climate change. Its weather is a simplified version of our own. Locked within its rocks and polar caps lie records of changing climate over eons.

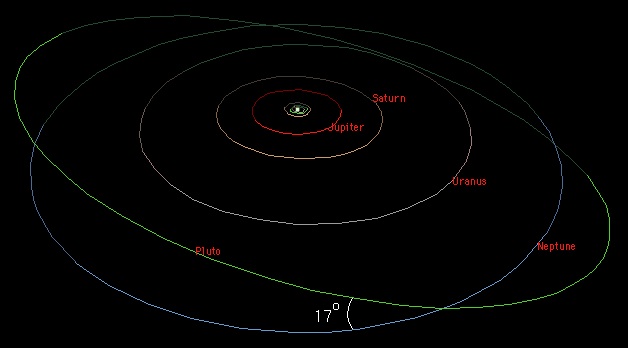

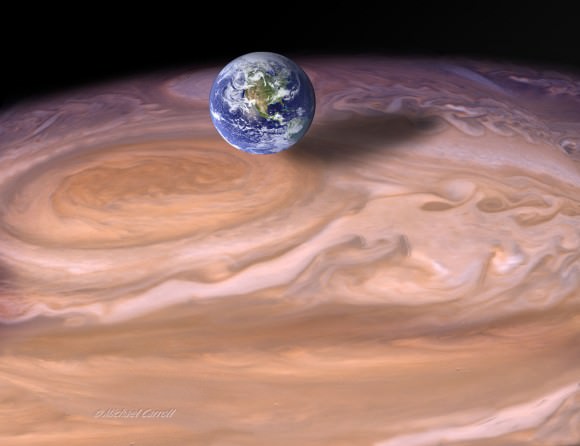

But fans of really extreme weather must venture further out, to the outer planets. Jupiter and Saturn are giant balls of gas with no solid surface, and are known as the “gas giants.” They are truly gigantic: over a thousand Earths could fit within Jupiter itself.

The skies of Jupiter and Saturn are dominated by hydrogen and helium, the ancient building blocks of the solar system. Ammonia mixes in to produce a rich brew of complex chemistry, painting the clouds of Jupiter and Saturn in tans and grays. Lightning bolts sizzle through the clouds, powerful enough to electrify a small city for weeks. Ammonia forms rain and snow in the frigid skies. Jupiter’s Great Red Spot is a centuries-old cyclone large enough to swallow three Earths. Saturn has its own bizarre storms: a vast hexagon-shaped trough of clouds races across the northern hemisphere. Over the south pole, a vast whirlpool gazes from concentric clouds like a Cyclops.

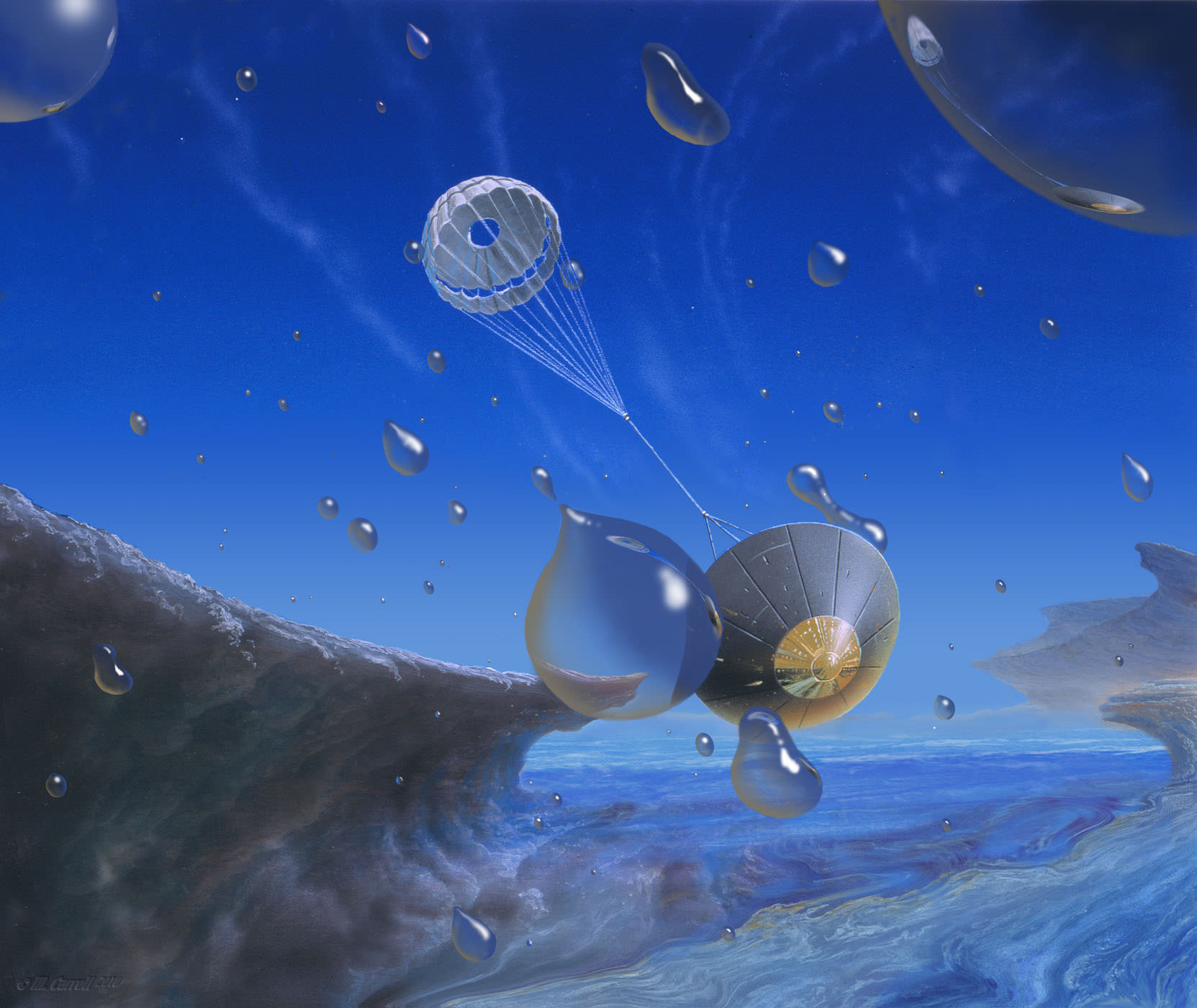

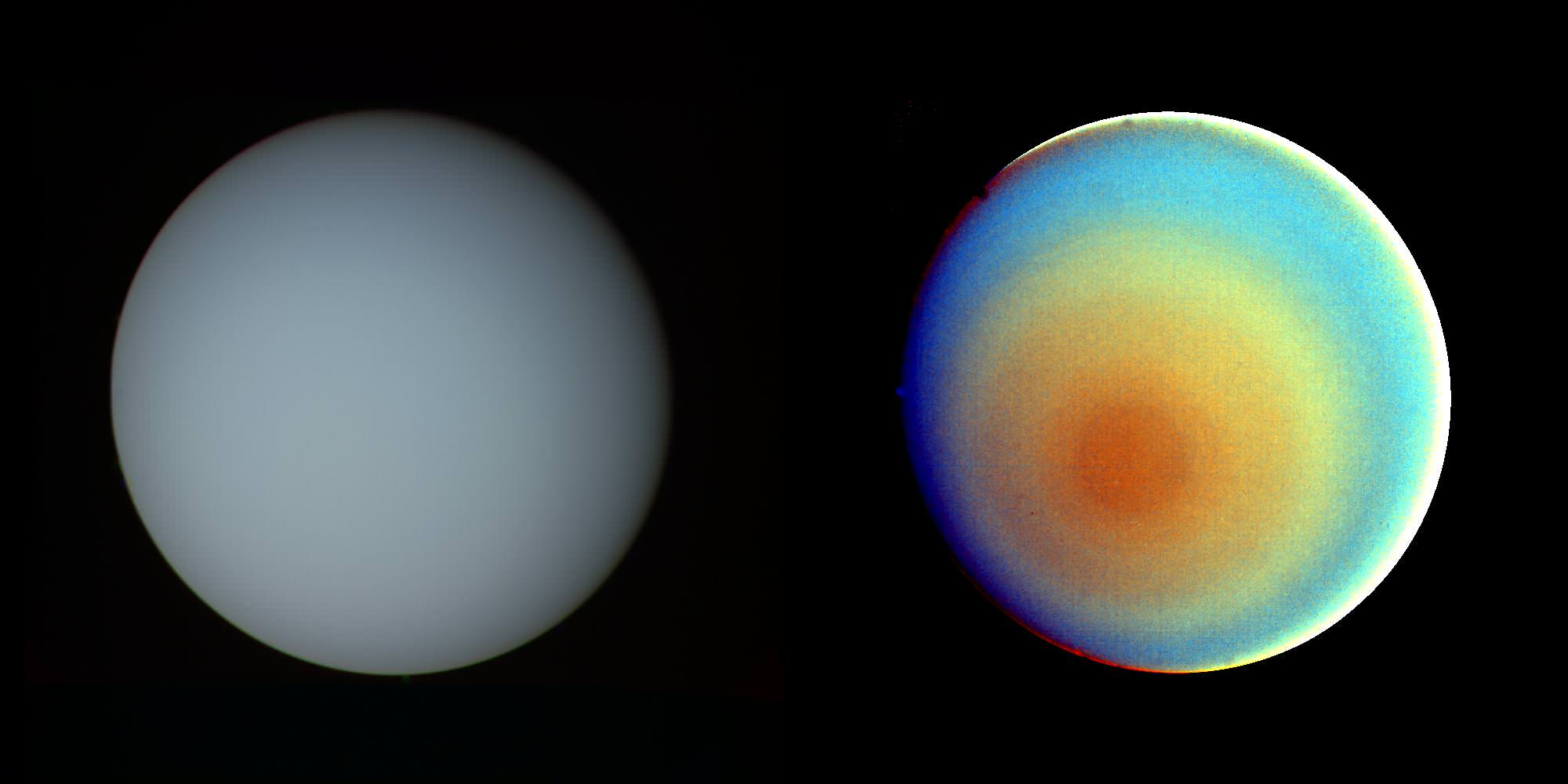

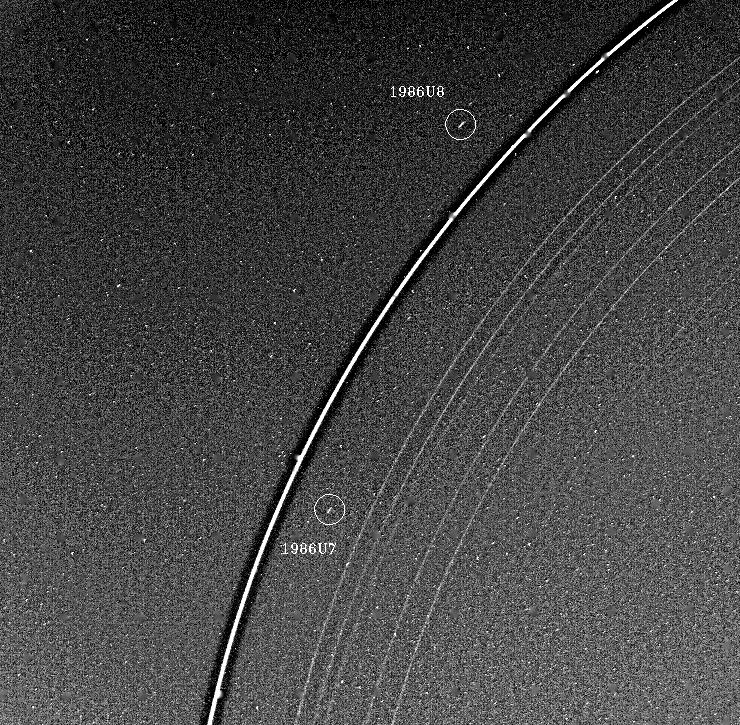

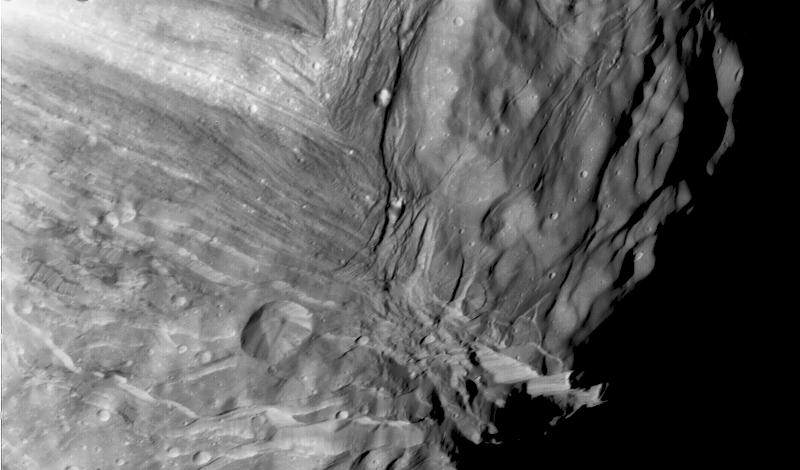

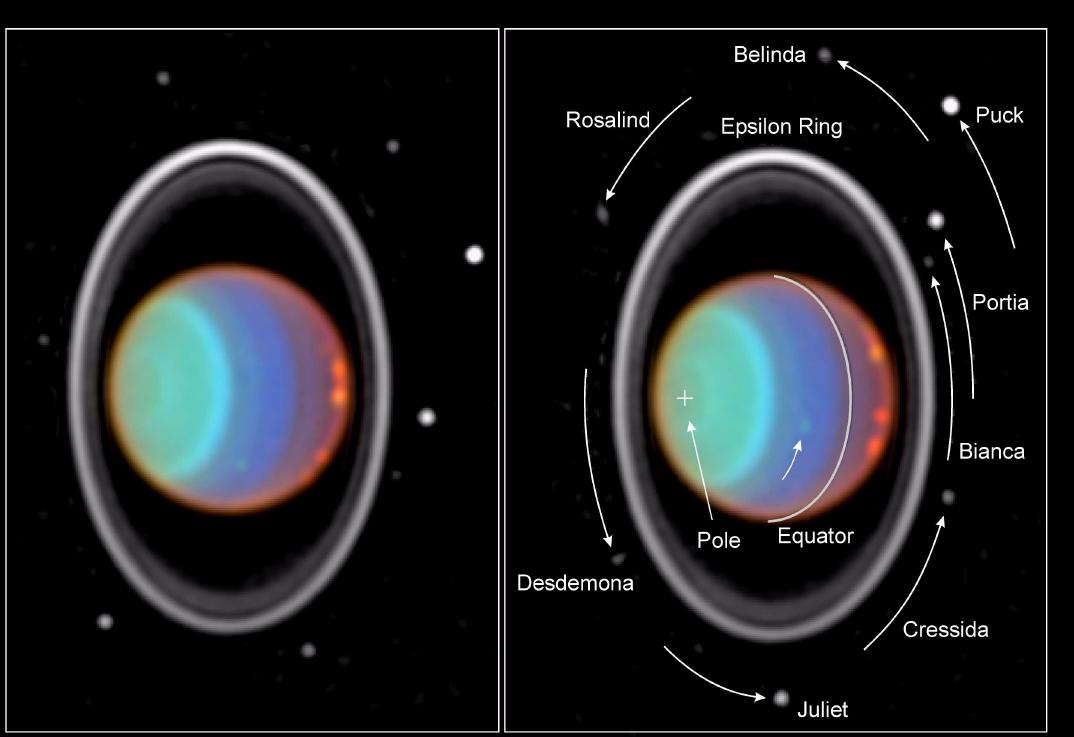

Beyond Jupiter and Saturn lie the “ice giants”, Uranus and Neptune. These behemoths host atmospheres of poisonous brews chilled to cryogenic temperatures. Methane tints Uranus and Neptune blue. Neptune’s clear air reveals a teal cloud deck. Hydrocarbon hazes tinge Uranus to a paler shade of blue-green. Neptune’s clear air is somewhat of a mystery to scientists. This may be because cloud-forming particles can’t stay airborne long enough to become visible clouds. Some scientists propose that Neptune’s abundant methane rains may condense so rapidly that within a few seconds tiny methane raindrops swell to something the size of a beachball. There are no clouds adrift, because methane rains out of the atmosphere too quickly.

One of the strangest cases of bizarre weather comes to us from Neptune’s moon Triton. Triton’s meager nitrogen air is tied to the freezing and thawing of polar ices, also composed of nitrogen. Triton’s entire atmosphere collapses twice a year, when it’s winter on one of the poles. At that time of year, all of Triton’s air migrates to the winter pole, where it freezes to the ground. The moon only has “weather” during the spring and fall; its atmosphere exists only during those seasons.

So, the next time you contemplate complaining about the heat, think of Venus. And if it’s blizzards you worry about, find comfort in Triton: at least our atmosphere doesn’t disappear in winter!

For more on the subject, see Michael Carroll’s newest book, Drifting on Alien Winds: Exploring the Skies and Weather of Other Worlds from Springer.