Here on Earth, we tend to take time for granted, never suspected that the increments with which we measure it are actually quite relative. The ways in which we measure our days and years, for example, are actually the result of our planet’s distance from the Sun, the time it takes to orbit, and the time it takes to rotate on its axis. The same is true for the other planets in our Solar System.

While we Earthlings count on a day being about 24 hours from sunup to sunup, the length of a single day on another planet is quite different. In some cases, they are very short, while in others, they can last longer than years – sometimes considerably! Let’s go over how time works on other planets and see just how long their days can be, shall we?

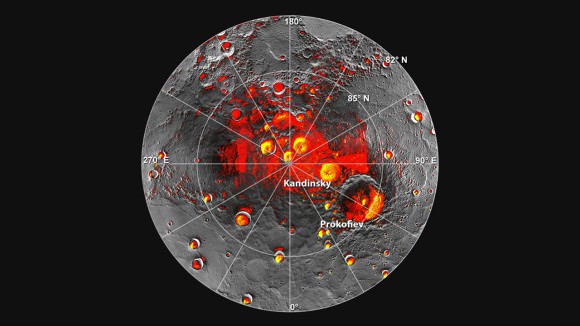

A Day On Mercury:

Mercury is the closest planet to our Sun, ranging from 46,001,200 km at perihelion (closest to the Sun) to 69,816,900 km at aphelion (farthest). Since it takes 58.646 Earth days for Mercury to rotate once on its axis – aka. its sidereal rotation period – this means that it takes just over 58 Earth days for Mercury to experience a single day.

However, this is not to say that Mercury experiences two sunrises in just over 58 days. Due to its proximity to the Sun and rapid speed with which it circles it, it takes the equivalent of 175.97 Earth days for the Sun to reappear in the same place in the sky. Hence, while the planet rotates once every 58 Earth days, it is roughly 176 days from one sunrise to the next on Mercury.

What’s more, it only takes Mercury 87.969 Earth days to complete a single orbit of the Sun (aka. its orbital period). This means a year on Mercury is the equivalent of about 88 Earth days, which in turn means that a single Mercurian (or Hermian) year lasts just half as long as a Mercurian day.

What’s more, Mercury’s northern polar regions are constantly in the shade. This is due to it’s axis being tilted at a mere 0.034° (compared to Earth’s 23.4°), which means that it does not experience extreme seasonal variations where days and nights can last for months depending on the season. On the poles of Mercury, it is always dark and shady. So you could say the poles are in a constant state of twilight.

A Day On Venus:

Also known as “Earth’s Twin”, Venus is the second closest planet to our Sun – ranging from 107,477,000 km at perihelion to 108,939,000 km at aphelion. Unfortunately, Venus is also the slowest moving planet, a fact which is made evident by looking at its poles. Whereas every other planet in the Solar System has experienced flattening at their poles due to the speed of their spin, Venus has experienced no such flattening.

Venus has a rotational velocity of just 6.5 km/h (4.0 mph) – compared to Earth’s rational velocity of 1,670 km/h (1,040 mph) – which leads to a sidereal rotation period of 243.025 days. Technically, it is -243.025 days, since Venus’ rotation is retrograde. This means that Venus rotates in the direction opposite to its orbital path around the Sun.

So if you were above Venus’ north pole and watched it circle around the Sun, you would see it is moving clockwise, whereas its rotation is counter-clockwise. Nevertheless, this still means that Venus takes over 243 Earth days to rotate once on its axis. However, much like Mercury, Venus’ orbital speed and slow rotation means that a single solar day – the time it takes the Sun to return to the same place in the sky – lasts about 117 days.

So while a single Venusian (or Cytherean) year works out to 224.701 Earth days, it experiences less than two full sunrises and sunsets in that time. In fact, a single Venusian/Cytherean year lasts as long as 1.92 Venusian/Cytherean days. Good thing Venus has other things in common With Earth, because it is sure isn’t its diurnal cycle!

A Day On Earth:

When we think of a day on Earth, we tend to think of it as a simple 24 hour interval. In truth, it takes the Earth exactly 23 hours 56 minutes and 4.1 seconds to rotate once on its axis. Meanwhile, on average, a solar day on Earth is 24 hours long, which means it takes that amount of time for the Sun to appear in the same place in the sky. Between these two values, we say a single day and night cycle lasts an even 24.

At the same time, there are variations in the length of a single day on the planet based on seasonal cycles. Due to Earth’s axial tilt, the amount of sunlight experienced in certain hemispheres will vary. The most extreme case of this occurs at the poles, where day and night can last for days or months depending on the season.

At the North and South Poles during the winter, a single night can last up to six months, which is known as a “polar night”. During the summer, the poles will experience what is called a “midnight sun”, where a day lasts a full 24 hours. So really, days are not as simple as we like to imagine. But compared to the other planets in the Solar System, time management is still easier here on Earth.

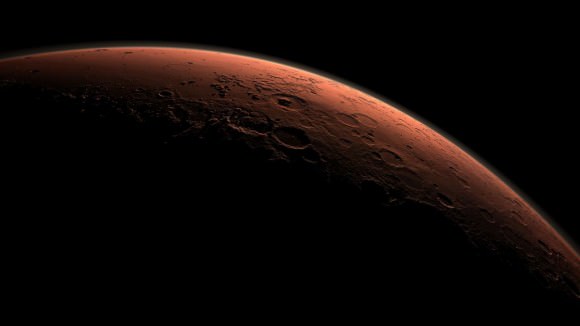

A Day On Mars:

In many respects, Mars can also be called “Earth’s Twin”. In addition to having polar ice caps, seasonal variations , and water (albeit frozen) on its surface, a day on Mars is pretty close to what a day on Earth is. Essentially, Mars takes 24 hours 37 minutes and 22 seconds to complete a single rotation on its axis. This means that a day on Mars is equivalent to 1.025957 days.

The seasonal cycles on Mars, which are due to it having an axial tilt similar to Earth’s (25.19° compared to Earth’s 23.4°), are more similar to those we experience on Earth than on any other planet. As a result, Martian days experience similar variations, with the Sun rising sooner and setting later in the summer and then experiencing the reverse in the winter.

However, seasonal variations last twice as long on Mars, thanks to Mars’ being at a greater distance from the Sun. This leads to the Martian year being about two Earth years long – 686.971 Earth days to be exact, which works out to 668.5991 Martian days (or Sols). As a result, longer days and longer nights can be expected last much longer on the Red Planet. Something for future colonists to consider!

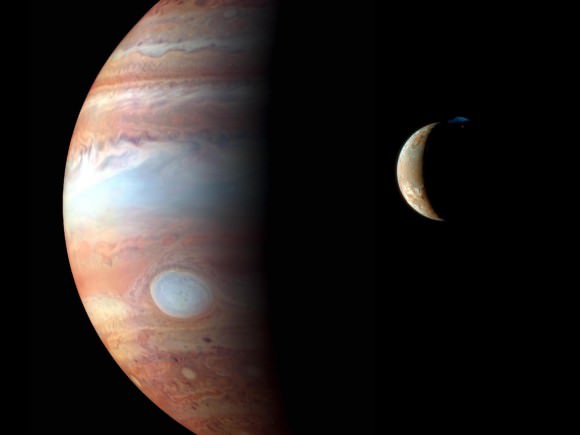

A Day On Jupiter:

Given the fact that it is the largest planet in the Solar System, one would expect that a day on Jupiter would last a long time. But as it turns out, a Jovian day is officially only 9 hours, 55 minutes and 30 seconds long, which means a single day is just over a third the length of an Earth day. This is due to the gas giant having a very rapid rotational speed, which is 12.6 km/s (45,300 km/h, or 28148.115 mph) at the equator. This rapid rotational speed is also one of the reasons the planet has such violent storms.

Note the use of the word officially. Since Jupiter is not a solid body, its upper atmosphere undergoes a different rate of rotation compared to its equator. Basically, the rotation of Jupiter’s polar atmosphere is about 5 minutes longer than that of the equatorial atmosphere. Because of this, astronomers use three systems as frames of reference.

System I applies from the latitudes 10° N to 10° S, where its rotational period is the planet’s shortest, at 9 hours, 50 minutes, and 30 seconds. System II applies at all latitudes north and south of these; its period is 9 hours, 55 minutes, and 40.6 seconds. System III corresponds to the rotation of the planet’s magnetosphere, and it’s period is used by the IAU and IAG to define Jupiter’s official rotation (i.e. 9 hours 44 minutes and 30 seconds)

So if you could, theoretically, stand on the cloud tops of Jupiter (or possibly on a floating platform in geosynchronous orbit), you would witness the sun rising an setting in the space of less than 10 hours from any latitude. And in the space of a single Jovian year, the sun would rise and set a total of about 10,476 times.

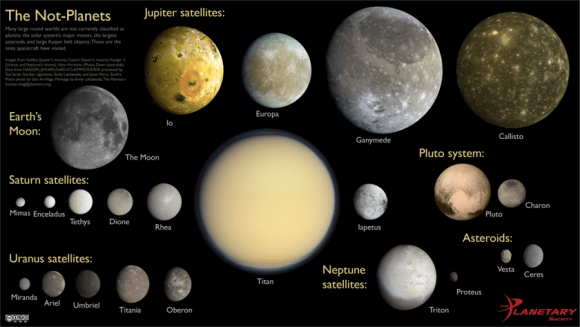

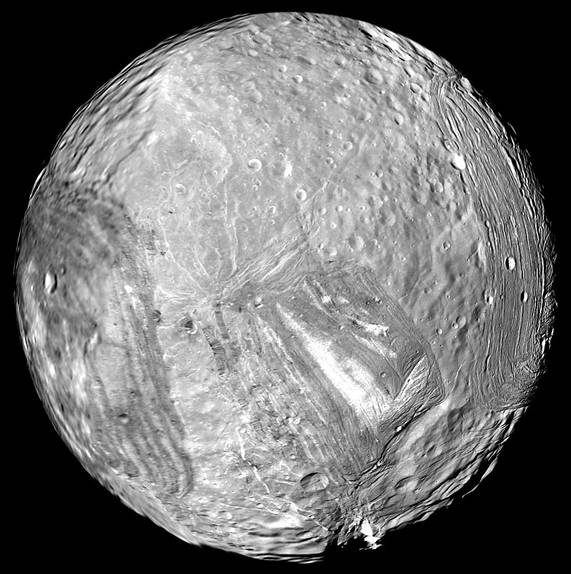

A Day On Saturn:

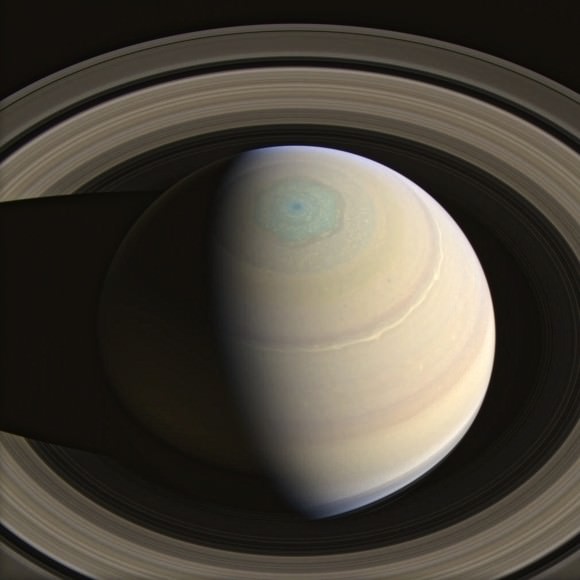

Saturn’s situation is very similar to that of Jupiter’s. Despite its massive size, the planet has an estimated rotational velocity of 9.87 km/s (35,500 km/h, or 22058.677 mph). As such Saturn takes about 10 hours and 33 minutes to complete a single sidereal rotation, making a single day on Saturn less than half of what it is here on Earth. Here too, this rapid movement of the atmosphere leads to some super storms, not to mention the hexagonal pattern around the planet’s north pole and a vortex storm around its south pole.

And, also like Jupiter, Saturn takes its time orbiting the Sun. With an orbital period that is the equivalent of 10,759.22 Earth days (or 29.4571 Earth years), a single Saturnian (or Cronian) year lasts roughly 24,491 Saturnian days. However, like Jupiter, Saturn’s atmosphere rotates at different speed depending on latitude, which requires that astronomers use three systems with different frames of reference.

System I encompasses the Equatorial Zone, the South Equatorial Belt and the North Equatorial Belt, and has a period of 10 hours and 14 minutes. System II covers all other Saturnian latitudes, excluding the north and south poles, and have been assigned a rotation period of 10 hr 38 min 25.4 sec. System III uses radio emissions to measure Saturn’s internal rotation rate, which yielded a rotation period of 10 hr 39 min 22.4 sec.

Using these various systems, scientists have obtained different data from Saturn over the years. For instance, data obtained during the 1980’s by the Voyager 1 and 2 missions indicated that a day on Saturn was 10 hours 39 minutes and 24 seconds long. In 2004, data provided by the Cassini-Huygens space probe measured the planet’s gravitational field, which yielded an estimate of 10 hours, 45 minutes, and 45 seconds (± 36 sec).

In 2007, this was revised by researches at the Department of Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences, UCLA, which resulted in the current estimate of 10 hours and 33 minutes. Much like with Jupiter, the problem of obtaining accurate measurements arises from the fact that, as a gas giant, parts of Saturn rotate faster than others.

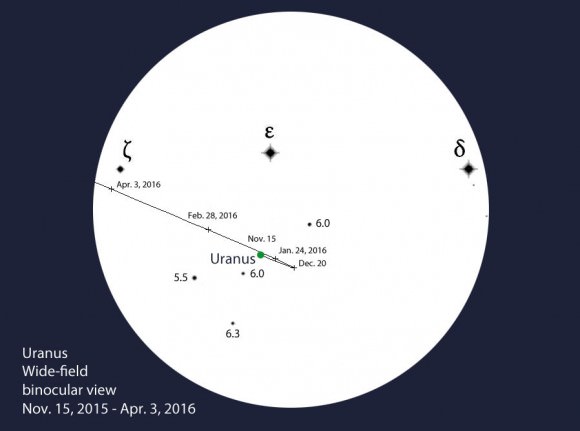

A Day On Uranus:

When we come to Uranus, the question of how long a day is becomes a bit complicated. One the one hand, the planet has a sidereal rotation period of 17 hours 14 minutes and 24 seconds, which is the equivalent of 0.71833 Earth days. So you could say a day on Uranus lasts almost as long as a day on Earth. It would be true, were it not for the extreme axial tilt this gas/ice giant has going on.

With an axial tilt of 97.77°, Uranus essentially orbits the Sun on its side. This means that either its north or south pole is pointed almost directly at the Sun at different times in its orbital period. When one pole is going through “summer” on Uranus, it will experience 42 years of continuous sunlight. When that same pole is pointed away from the Sun (i.e. a Uranian “winter”), it will experience 42 years of continuous darkness.

Hence, you might say that a single day – from one sunrise to the next – lasts a full 84 years on Uranus! In other words, a single Uranian day is the same amount of time as a single Uranian year (84.0205 Earth years).

In addition, as with the other gas/ice giants, Uranus rotates faster at certain latitudes. Ergo, while the planet’s rotation is 17 hours and 14.5 minutes at the equator, at about 60° south, visible features of the atmosphere move much faster, making a full rotation in as little as 14 hours.

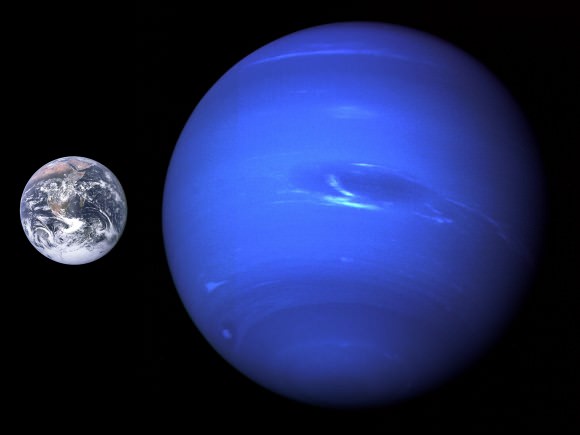

A Day On Neptune:

Last, but not least, we have Neptune. Here too, measuring a single day is somewhat complicated. For instance, Neptune’s sidereal rotation period is roughly 16 hours, 6 minutes and 36 seconds (the equivalent of 0.6713 Earth days). But due to it being a gas/ice giant, the poles of the planet rotate faster than the equator.

Whereas the planet’s magnetic field has a rotational speed of 16.1 hours, the wide equatorial zone rotates with a period of about 18 hour. Meanwhile, the polar regions rotate the fastest, at a period of 12 hours. This differential rotation is the most pronounced of any planet in the Solar System, and it results in strong latitudinal wind shear.

In addition, the planet’s axial tilt of 28.32° results in seasonal variations that are similar to those on Earth and Mars. The long orbital period of Neptune means that the seasons last for forty Earth years. But because its axial tilt is comparable to Earth’s, the variation in the length of its day over the course of its long year is not any more extreme.

As you can see from this little rundown of the different planets in our Solar System, what constitutes a day depends entirely on your frame of reference. In addition to it varying depending on the planet in question, you also have to take into account seasonal cycles and where on the planet the measurements are being taken from.

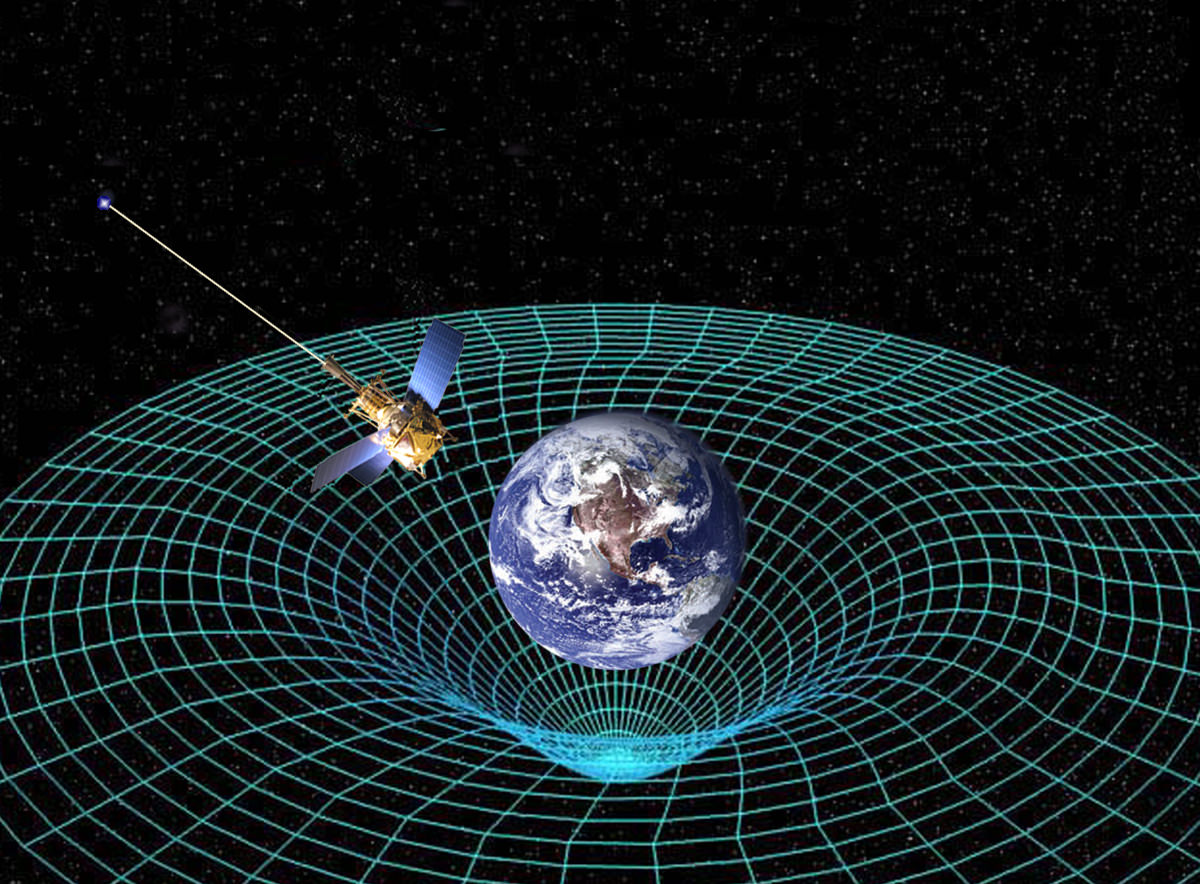

As Einstein summarized, time is relative to the observer. Based on your inertial reference frame, its passage will differ. And when you are standing on a planet other than Earth, your concept of day and night, which is set to Earth time (and a specific time zone) is likely to get pretty confused!

We have written many interesting articles about how time is measured on other planets here at Universe Today. For example, here’s How Long Is A Year On The Other Planets?, Which Planet Has the Longest Day?, The Rotation of Venus, How Long Is A Day on Mars? and How Long Is A Day On Jupiter?.

If you are looking for more information, check out Our Solar System at Space.com

Astronomy Cast has episodes on all the planets, including Episode 49: Mercury, and Episode 95: Humans to Mars, Part 2 – Colonists

![Space Shuttle Endeavour sillouetted against the atmosphere. The orange layer is the troposphere, the white layer is the stratosphere and the blue layer the mesosphere.[1] (The shuttle is actually orbiting at an altitude of more than 320 km (200 mi), far above all three layers.) Credit: NASA](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/Endeavour_silhouette_STS-130-580x387.jpg)