[/caption]

Where is NASA going next to probe our solar system? The space agency announced today they have selected three proposals as candidates for the agency’s next space venture to another celestial body in our solar system. The proposed missions would probe the atmosphere composition and crust of Venus; return a piece of a near-Earth asteroid for analysis; or drop a robotic lander into a basin at the moon’s south pole to return lunar rocks back to Earth for study. All three sound exciting!

Here are the finalists:

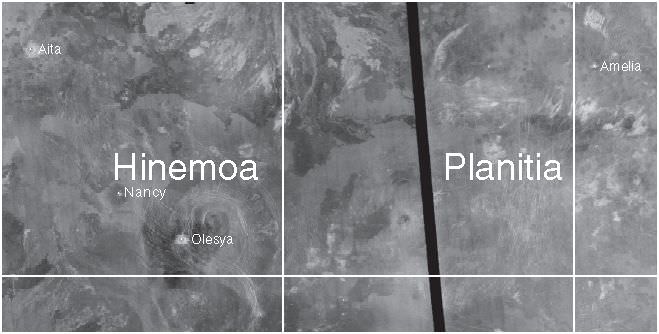

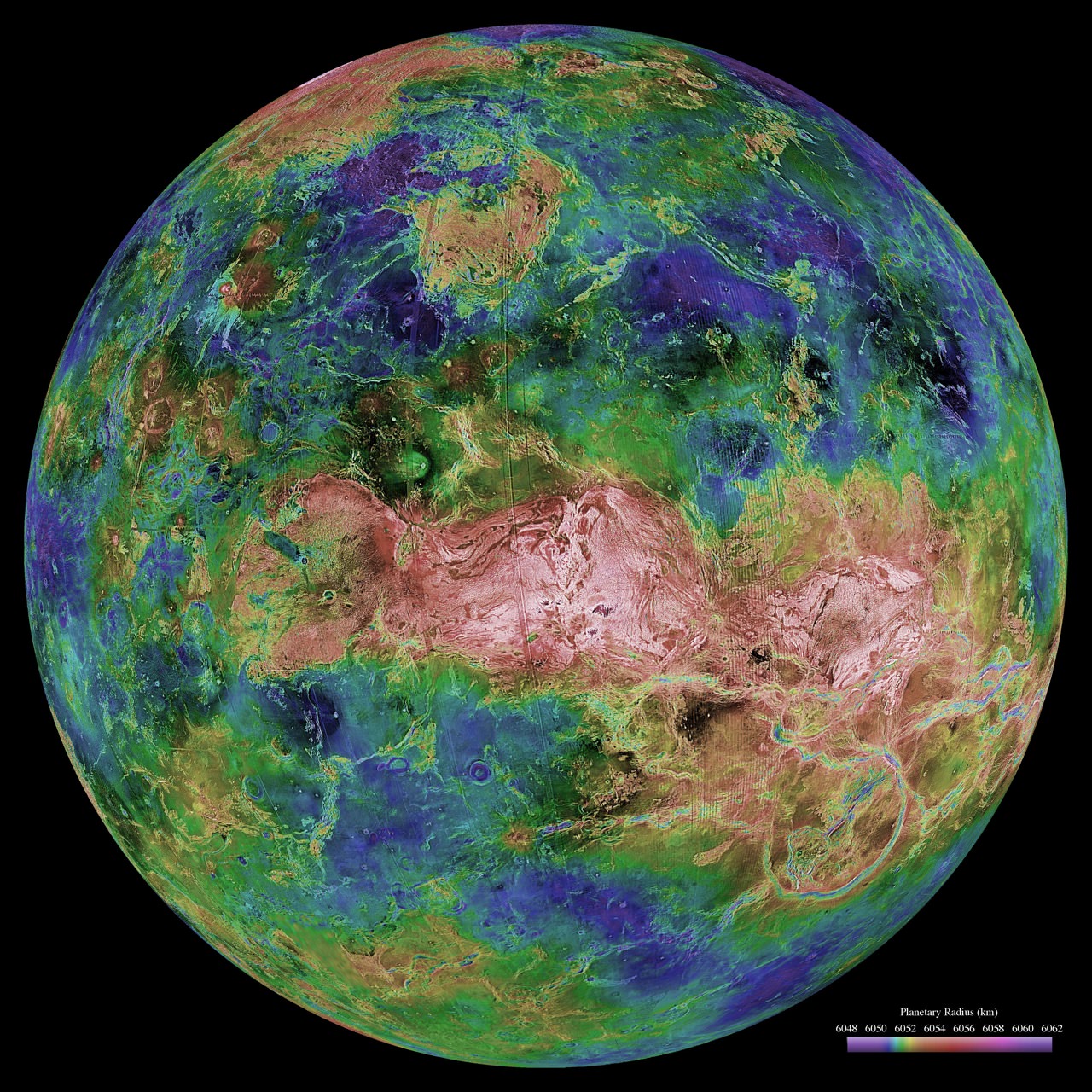

Surface and Atmosphere Geochemical Explorer, or SAGE, mission to Venus would release a probe to descend through the planet’s atmosphere. During descent, instruments would conduct extensive measurements of the atmosphere’s composition and obtain meteorological data. The probe then would land on the surface of Venus, where its abrading tool would expose both a weathered and a pristine surface area to measure its composition and mineralogy. Scientists hope to understand the origin of Venus and why it is so different from Earth. Larry Esposito of the University of Colorado in Boulder, is the principal investigator.

Origins Spectral Interpretation Resource Identification Security Regolith Explorer spacecraft, called Osiris-Rex, would rendezvous and orbit a primitive asteroid. After extensive measurements, instruments would collect more than two ounces of material from the asteriod’s surface for return to Earth. The returned samples would help scientists better undertand and answer long-held questions about the formation of our solar system and the origin of complex molecules necessary for life. Michael Drake, of the University of Arizona in Tucson, is the principal investigator.

MoonRise: Lunar South Pole-Aitken Basin Sample Return Mission would place a lander in a broad basin near the moon’s south pole and return approximately two pounds of lunar materials for study. This region of the lunar surface is believed to harbor rocks excavated from the moon’s mantle. The samples would provide new insight into the early history of the Earth-moon system. Bradley Jolliff, of Washington University in St. Louis, is the principal investigator.

The final project will be selected in mid-2011, and for now, the three finalists will receive approximately $3.3 million in 2010 to conduct a 12-month mission concept study that focuses on implementation feasibility, cost, management and technical plans. Studies also will include plans for educational outreach and small business opportunities.

The selected mission must be ready for launch no later than Dec. 30, 2018. Mission cost, excluding the launch vehicle, is limited to $650 million.

“These are projects that inspire and excite young scientists, engineers and the public,” said Ed Weiler, associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “These three proposals provide the best science value among eight submitted to NASA this year.”

The final selection will become the third mission in the program. New Horizons, launched in 2006, will fly by the Pluto-Charon system in 2015 then target another Kuiper Belt object for study. The second mission, called Juno, is designed to orbit Jupiter from pole to pole for the first time, conducting an in-depth study of the giant planet’s atmosphere and interior. It is slated for launch in August 2011.

Visit the New Frontiers program site for more information.