Welcome to the 583rd Carnival of Space! The Carnival is a community of space science and astronomy writers and bloggers, who submit their best work each week for your benefit. We have a fantastic roundup today so now, on to this week’s worth of stories!

Continue reading “Carnival of Space #583”

NASA Has Awarded a Contract to Study Flying Drones on Venus

In the coming decades, NASA and other space agencies hope to mount some ambitious missions to other planets in our Solar System. In addition to studying Mars and the outer Solar System in greater detail, NASA intends to send a mission to Venus to learn more about the planet’s past. This will include studying Venus’ upper atmosphere to determine if the planet once had liquid water (and maybe even life) on its surface.

In order to tackle this daunting challenge, NASA recently partnered with Black Swift Technologies – a Boulder-based company specializing in unmanned aerial systems (UAS) – to build a drone that could survive in Venus’ upper atmosphere. This will be no easy task, but if their designs should prove equal to the task, NASA will be awarding the company a lucrative contract for a Venus aerial drone.

In recent years, NASA has taken a renewed interest in Venus, thanks to climate models that have indicated that it (much like Mars) may have also had liquid water on its surface at one time. This would have likely consisted of a shallow ocean that covered much of the planet’s surface roughly 2 billion years ago, before the planet suffered a runaway Greenhouse Effect that left it the hot and hellish world it is today.

In addition, a recent study – which included scientists from NASA’s Ames Research Center and Jet Propulsion Laboratory – indicated that there could be microbial life in Venus’ cloud tops. As such, there is considerable motivation to send aerial platforms to Venus that would be capable of studying Venus’ cloud tops and determining if there are any traces of organic life or indications of the planet’s past surface water there.

As Jack Elston, the co-founded of Black Swift Technologies, explained in an interview with the Daily Camera:

“They’re looking for vehicles to explore just above the cloud layer. The pressure and temperatures are similar to what you’d find on Earth, so it could be a good environment for looking for evidence of life. The winds in the upper atmosphere of Venus are incredibly strong, which creates design challenge.”

To meet this challenge, the company intends to create a drone that will use these strong winds to keep the craft aloft while reducing the amount of electricity it needs. So far, NASA has awarded an initial six-month contract to the company to design a drone and provided specifications on what it needs. This contract included a $125,000 grant by the federal governments’ Small Business Innovation Research program.

This program aims to encourage “domestic small businesses to engage in Federal Research/Research and Development (R/R&D) that has the potential for commercialization.” The company hopes to use some of this grant money to take on more staff and build a drone that NASA would be confident about sending int Venus’ upper atmosphere, where conditions are particularly challenging.

As Elston explained to Universe Today via email, these challenges represent an opportunity for innovation:

“Our project centers around a unique aircraft and method for harvesting energy from Venus’s upper atmosphere that doesn’t require additional sources of energy for propulsion. Our experience working on unmanned aircraft systems that interact with severe convective storms on Earth will hopefully provide a valuable contribution to the ongoing discussion for how best to explore this turbulent environment. Additionally, the work we do will help inform better designs of our own aircraft and should lead to longer observation times and more robust aircraft to observe everything from volcanic plumes to hurricanes.”

At the end of the six month period, Black Swift will present its concept to NASA for approval. “If they like what we’ve come up with, they’ll fund another two-year project to build prototypes,” said Elston. “That second-phase contract is expected to be worth $750,000.”

This is not the first time that Black Swift has partnered with NASA to created unmanned aerial vehicles to study harsh environments. Last year, the company was awarded a second phase contract worth $875,000 to build a drone that could monitor the temperature, gas levels, winds and pressure levels inside the volcanoes of Costa Rica. After a series of test flights, the drone is expected to be deployed to Hawaii, where it will study the geothermal activity occurring there.

If BlackSwift’s concept for a Venus drone makes the cut, their aerial drone will join other mission concepts like the DAVINCI spacecraft, the Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy (VERITAS) spacecraft, the Venus Atmospheric Maneuverable Platform (VAMP), or Russia’s Venera-D mission – which is currently scheduled to explore Venus during the late 2020s.

A number of other concepts are being investigated for exploring Venus’ surface to learn more about its geological history. These include a “Steampunk” (i.e. analog) rover that would rely on no electronic parts, or a vehicle that uses a Stored-Chemical Energy and Power System (SCEPS) – aka. a Sterling engine – to conduct in-situ exploration.

All of these missions aim to reach Venus and brave its harsh conditions in order to determine whether or not “Earth’s Sister Planet” was once a more habitable planet, and how it evolved over time to become the hot and hellish place it is today.

Further Reading: The Drive, Daily Camera

Jupiter and Venus Change Earth’s Orbit Every 405,000 Years

It is a well-known fact among Earth scientists that our planet periodically undergoes major changes in its climate. Over the course of the past 200 million years, our planet has experienced four major geological periods (the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous and Cenozoic) and one major ice age (the Pliocene-Quaternary glaciation), all of which had a drastic impact on plant and animal life, as well as effecting the course of species evolution.

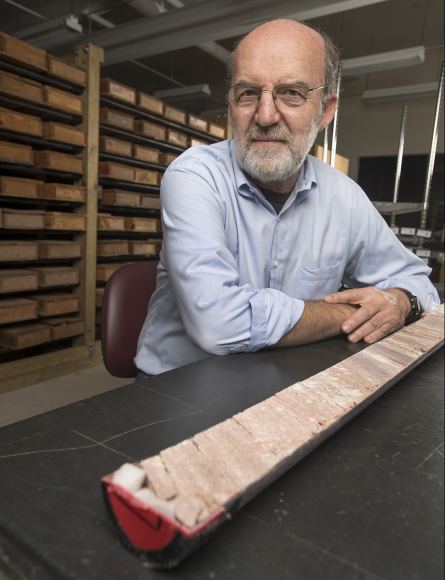

For decades, geologists have also understood that these changes are due in part to gradual shifts in the Earth’s orbit, which are caused by Venus and Jupiter, and repeat regularly every 405,000 years. But it was not until recently that a team of geologists and Earth scientists unearthed the first evidence of these changes – sediments and rock core samples that provide a geological record of how and when these changes took place.

The study which describes their findings, titled “Empirical evidence for stability of the 405-kiloyear Jupiter–Venus eccentricity cycle over hundreds of millions of years”, recently appeared in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. The study was led by Dennis V. Bent, a, a Board of Governors professor from Rutgers University–New Brunswick, and included members from the Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory, the Berkeley Geochronology Center, the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona, and multiple universities.

As noted, the idea that Earth experiences periodic changes in its climate (which are related to changes in its orbit) has been understood for almost a century. These changes consist of Milankovitch Cycles, which consist of a 100,000-year cycle in the eccentricity of Earth’s orbit, a 41,000-year cycle in the tilt of Earth’s axis relative to its orbital plane, and a 21,000-year cycle caused by changes in the planet’s axis.

Combined with the 405,000-year swing, which is the result of Venus and Jupiter’s gravitational influence, these shifts cause changes in how much solar energy reaches parts of our planet, which in turn influences Earth’s climate. Based on fossil records, these cycles are also known to have had a profound impact on life on Earth, which likely had an effect on the course of species of evolution. As Prof. Bent explained in a Rutgers Today press release:

“The climate cycles are directly related to how Earth orbits the sun and slight variations in sunlight reaching Earth lead to climate and ecological changes. The Earth’s orbit changes from close to perfectly circular to about 5 percent elongated especially every 405,000 years.”

For the sake of their study, Prof. Kent and his colleagues obtained sediment samples from the Newark basin, a prehistoric lake that spanned most of New Jersey, and a core rock sample from the Chinle Formation in Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona. This core rock measured about 518 meters (1700 feet) long, 6.35 cm (2.5 inches) in diameter, and was dated to the Triassic Period – ca. 202 to 253 million years ago.

The team then linked reversals in Earth’s magnetic field – where the north and south pole shift – to sediments with and without zircons (minerals with uranium that allow for radioactive dating) as well as to climate cycles in the geological record. What these showed was that the 405,000-years cycle is the most regular astronomical pattern linked to Earth’s annual orbit around the Sun.

The results further indicated that the cycle been stable for hundreds of millions of years and is still active today. As Prof. Kent explained, this constitutes the first verifiable evidence that celestial mechanics have played a historic role in natural shifts in Earth’s climate. As Prof. Kent indicated:

“It’s an astonishing result because this long cycle, which had been predicted from planetary motions through about 50 million years ago, has been confirmed through at least 215 million years ago. Scientists can now link changes in the climate, environment, dinosaurs, mammals and fossils around the world to this 405,000-year cycle in a very precise way.”

Previously, astronomers were able to calculate this cycle reliably back to around 50 million years, but found that the problem became too complex prior to this because too many shifting motions came into play. “There are other, shorter, orbital cycles, but when you look into the past, it’s very difficult to know which one you’re dealing with at any one time, because they change over time,” said Prof. Kent. “The beauty of this one is that it stands alone. It doesn’t change. All the other ones move over it.”

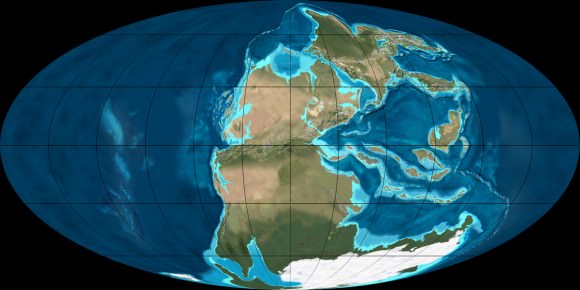

In addition, scientists were unable to obtain accurate dates as to when Earth’s magnetic field reversed for 30 million years of the Late Triassic – between ca. 201.3 and 237 million years ago. This was a crucial period for the evolution of terrestrial life because it was when the Supercontinent of Pangaea broke up, and also when the dinosaurs and mammals first appeared.

This break-up led to the formation of the Atlantic Ocean as the continents drifted apart and coincided with a mass extinction event by the end of the period that effected the dinosaurs. With this new evidence, geologists, paleontologists and Earth scientists will be able to develop very precise timelines and accurately categorize fossil evidence dated to this period, which show differences and similarities over wide-ranging areas.

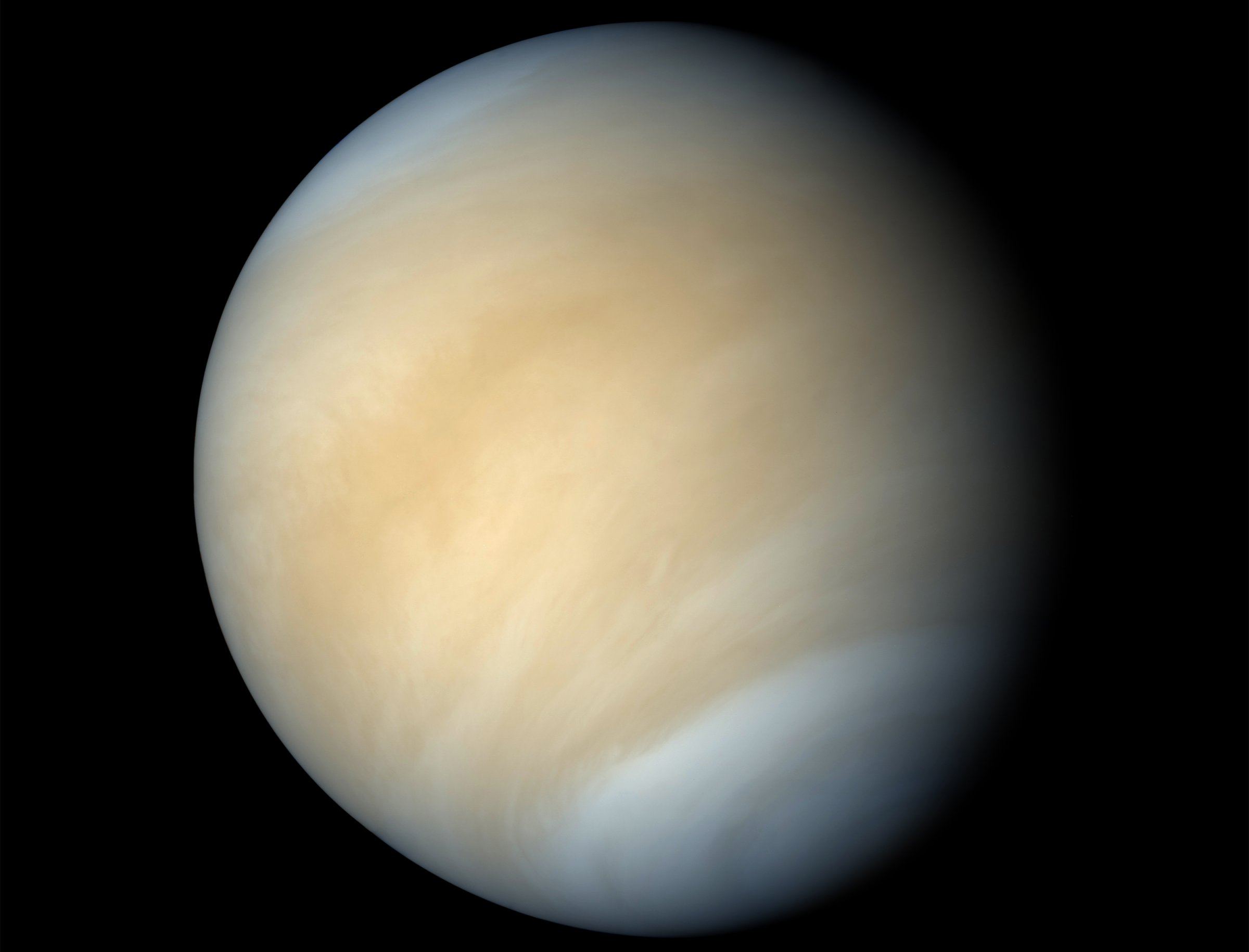

Could There Be Life in the Cloudtops of Venus?

In the search for life beyond Earth, scientists have turned up some very interesting possibilities and clues. On Mars, there are currently eight functioning robotic missions on the surface of or in orbit investigating the possibility of past (and possibly present) microbial life. Multiple missions are also being planned to explore moons like Titan, Europa, and Enceladus for signs of methanogenic or extreme life.

But what about Earth’s closest neighboring planet, Venus? While conditions on its surface are far too hostile for life as we know it there are those who think it could exist in its atmosphere. In a new study, a team of international researchers addressed the possibility that microbial life could be found in Venus’ cloud tops. This study could answer an enduring mystery about Venus’ atmosphere and lead to future missions to Earth’s “Sister Planet”.

The study, titled “Venus’ Spectral Signatures and the Potential for Life in the Clouds“, recently appeared in the journal Astrobiology. The study was led by Sanjay Limaye of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Space Science and Engineering Center and included members from NASA’s Ames Research Center, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California State Polytechnic University, the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences, and the University of Zielona Góra.

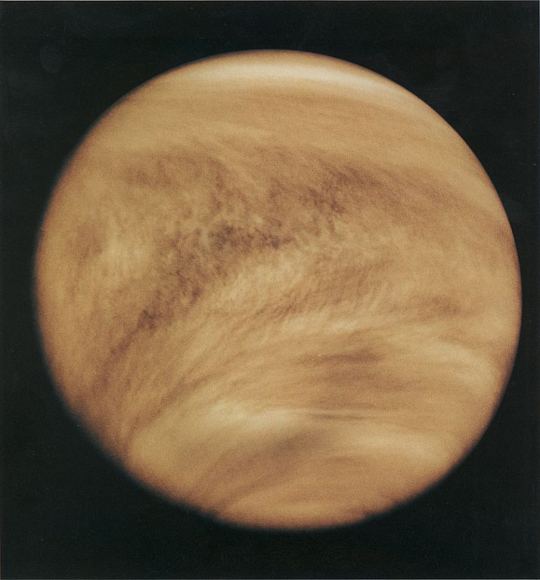

For the sake of their study, the team considered the presence of UV contrasts in Venus’ upper atmosphere. These dark patches have been a mystery since they were first observered nearly a century ago by ground-based telescopes. Since then, scientists have learned that they are made up of concentrated sulfuric acid and other unknown light-absorbing particles, which the team argues could be microbial life.

As Limaye indicated in a recent University of Wisconsin-Madison press statement:

“Venus shows some episodic dark, sulfuric rich patches, with contrasts up to 30 – 40 percent in the ultraviolet, and muted in longer wavelengths. These patches persist for days, changing their shape and contrasts continuously and appear to be scale dependent.”

To illustrate the possibility that these streaks are the result of microbial life, the team considered whether or not extreme bacteria could survive in Venus’ cloud tops. For instance, the lower cloud tops of Venus (47.5 to 50.5 km above the surface) are known to have moderate temperature conditions (~60 °C; 140 °F) and pressure conditions that are similar to that of Earth at sea level (101.325 kPa).

This is far more hospitable than conditions on the surface, where temperatures reach 737 K (462 C; 860 F) and atmospheric pressure is 9200 kPa (92 times that of Earth at sea level). In addition, they considered how on Earth, bacteria has been found at altitudes as high as 41 km (25 mi). On top of that, there are many cases where extreme bacteria here on Earth that could survive in an acidic environment.

As Rakesh Mogul, a professor of biological chemistry at California State Polytechnic University and a co-author on the study, indicated, “On Earth, we know that life can thrive in very acidic conditions, can feed on carbon dioxide, and produce sulfuric acid.” This is consistent with the presence of micron-sized sulfuric acid aerosols in Venus upper atmosphere, which could be a metabolic by-product.

In addition, the team also noted that according to some models, Venus had a habitable climate with liquid water on its surface for as long as two billion years – which is much longer than what is believed to have occurred on Mars. In short, they speculate that life could have evolved on the surface of Venus and been swept up into the atmosphere, where it survived as the planet experienced its runaway greenhouse effect.

This study expands on a proposal originally made by Harold Morowitz and famed astronomer Carl Sagan in 1967 and which was investigated by a series of probes sent to Venus between 1962 and 1978. While these missions indicated that surface conditions on Venus ruled out the possibility of life, they also noted that conditions in the lower and middle portions of Venus’ atmosphere – 40 to 60 km (25 – 27 mi) altitude – did not preclude the possibility of microbial life.

For years, Limaye has been revisiting the idea of exploring Venus’ atmosphere for signs of life. The inspiration came in part from a chance meeting at a teachers workshop with Grzegorz Slowik – from the University of Zielona Góra in Poland and a co-author on the study – who told him of how bacteria on Earth have light-absorbing properties similar to the particles that make up the dark patches observed in Venus’ clouds.

While no probe that has sampled Venus’ atmosphere has been capable of distinguishing between organic and inorganic particles, the ones that make up Venus’ dark patches do have comparable dimensions to some bacteria on Earth. According to Limaye and Mogul, these patches could therefore be similar to algae blooms on Earth, consisting of bacteria that metabolizes the carbon dioxide in Venus’ atmosphere and produces sulfuric acid aerosols.

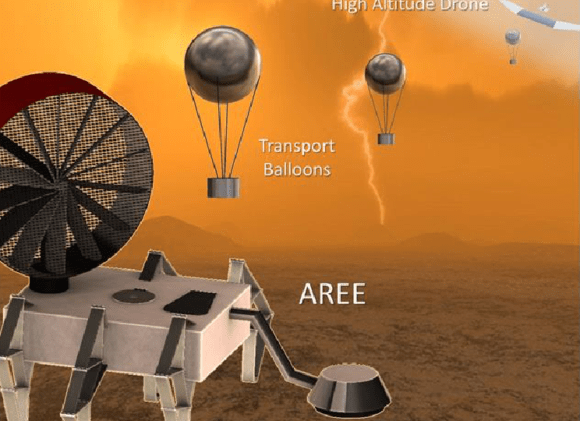

In the coming years, Venus’ atmosphere could be explored for signs of microbial life by a lighter than air aircraft. One possibility is the Venus Aerial Mobil Platform (VAMP), a concept currently being researched by Northrop Grumman (shown above). Much like lighter-than-air concepts being developed to explore Titan, this vehicle would float and fly around in Venus’ atmosphere and search the cloud tops for biosignatures.

Another possibility is NASA’s possible participation in the Russian Venera-D mission, which is currently scheduled to explore Venus during the late 2020s. This mission would consist of a Russian orbiter and lander to explore Venus’ atmosphere and surface while NASA would contribute a surface station and maneuverable aerial platform.

Another mystery that such a mission could explore, which has a direct bearing on whether or not life may still exist on Venus, is when Venus’ liquid water evaporated. In the last billion years or so, the extensive lava flows that cover the surface have either destroyed or covered up evidence of the planet’s early history. By sampling Venus’ clouds, scientists could determine when all of the planet’s liquid water disappeared, triggering the runaway greenhouse effect that turned it into a hellish landscape.

NASA is currently investigating other concepts to explore Venus’ hostile surface and atmosphere, including an analog robot and a lander that would use a Sterling engine to turn Venus’ atmosphere into a source of power. And with enough time and resources, we might even begin contemplating building floating cities in Venus atmosphere, complete with research facilities.

Further Reading: Space Science and Engineering Center, Astrobiology

What are the Chances Musk’s Space Tesla is Going to Crash Into Venus or Earth?

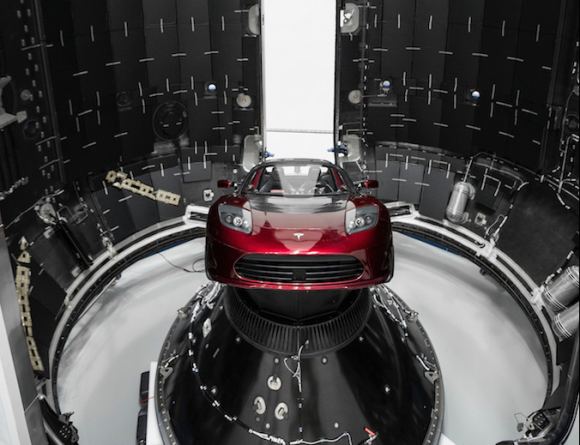

On February 6th, 2018, SpaceX successfully launched its Falcon Heavy rocket into orbit. This was a momentous occasion for the private aerospace company and represented a major breakthrough for spaceflight. Not only is the Falcon Heavy the most powerful rocket currently in service, it is also the first heavy launch vehicle that relies on reusable boosters (two of which were successfully retrieved after the launch).

Equally interesting was the rocket’s cargo, which consisted of Musk’s cherry-red Tesla Roadster with a spacesuit in the driver’s seat. According to Musk, this vehicle and its “pilot” (Starman), will eventually achieve a Hohmann Transfer Orbit with Mars and remain there for up to a billion years. However, according to a new study, there’s a small chance that the Roadster will collide with Venus or Earth instead in a few eons.

The study which raises this possibility recently appeared online under the title “The random walk of cars and their collision probabilities with planets.” The study was conducted by Hanno Rein, an assistant professor at the University of Toronto; Daniel Tamayo, a postdoctoral fellow with the Center for Planetary Sciences (CPS) and the Canadian Institute for Theoretical Astrophysics (CITA); and David Vokrouhlick of the Institute of Astronomy at Charles University in Prague.

As we indicated in a previous post, Musk’s original flight plan has the potential to place the Roadster into a stable orbit around Mars… after a fashion. According to Max Fagin, an aerospace engineer from Colorado and a space camp alumni, the Roadster will get close enough to Mars to establish an orbit by October of 2018. However, this orbit would not rule out close encounters with Earth over the course of the next few million years.

For the sake of their study, Rein and his colleagues considered how such close encounters might alter the Roadster’s orbit in that time. Using data from NASA’s HORIZONS interface to determine the initial positions of all Solar planets and the Roadster, the team calculated the likelihood of future close encounters between the vehicle and the terrestrial planets, and how likely a resulting collision would be.

As they indicated, the Roadster bears some similarities to Near-Earth Asteroids (NEAs) and ejecta from the Earth-Moon system. In short, NEAs permeate the inner Solar System, regularly crossing the orbits of terrestrial planets and experiencing close encounters with them (resulting in the occasional collision). In addition, ejecta from the Earth and Moon also experience close encounters with the terrestrial planets and collide with them.

However, the Tesla Roadster is unique in two key respects: For one, it originated from Earth rather than being pulled from the Asteroid Belt into the inner Solar System by strong resonances. Second, it had a higher ejection velocity when it left Earth, which tends to result in fewer impacts. “Given the peculiar initial conditions and even stranger object, it therefore remains an interesting question to probe its dynamics and eventual fate,” they claim.

Another challenge was how the probability of an impact will change drastically over time. While the chance of a collision can be ruled out in the short run (i.e. the next few years), the Roadster’s chaotic orbit is difficult to predict over the course of subsequent close encounters. As such, the team performed a statistical calculation to see how the orbit and velocity of the Roadster would change over time. As they state in their study:

“Given that the Tesla was launched from Earth, the two objects have intersecting orbits and repeatedly undergo close encounters. The bodies reach the same orbital longitude on their synodic timescale of ~2.8 yrs.”

They began by considering how the Roadster’s orbit would evolve over the course of its next 48 orbits, which would encompass the next 1000 years. They then expanded the analysis to consider long-term evolution, which encompassed 240 orbits over the course of the next 3.5 million years. What they found was that on a million-year timescale, the orbit of the Roadster remains in a region dominated by close encounters with Earth.

However, over time, their simulations show that the Roadster will experience changes in eccentricity due to resonant and secular effects. This will result in interactions more frequent interactions between the Roadster and Venus over time, and close encounters with Mars becoming possible. Over long enough timescales, the team even anticipates that interactions with Mercury’s orbit will be possible (though unlikely).

In the end, their simulations revealed that over the course of a million years and beyond, the probability of a collision with a terrestrial planet is unlikely, but not impossible. And while the odds are slim, they favor an eventual collision with Earth. Or as they put it:

“Although there were several close encounters with Mars in our simulations, none of them resulted in a physical collision. We find that there is a ~6% chance that the Tesla will collide with Earth and a ~2.5% chance that it will collide with Venus within the next 1 Myr. The collision rate goes down slightly with time. After 3 Myr the probability of a collision with Earth is ~11%. We observed only one collision with the Sun within 3 Myr.”

Given the Musk hoped that his Roadster would remain in orbit of Mars for one billion years, and that aliens might eventually find it, the prospect of it colliding with Earth or Venus is a bit of a letdown. Why bother sending such a unique payload into space if it’s just going to come back? Still, the odds that it will be drifting through space for millions of years remains a distinct possibility.

And if there are any worries that the Roadster will pose a threat to future missions or Earth itself, consider the message Starman was looking at during his ascent into space – Don’t Panic! Assuming humanity is even alive eons from now, the far greater danger will be that such an antique will burn up in our atmosphere. After millions of years, Starman is sure to be a big celebrity!

Further Reading: arXiv

Earth and Venus are the Same Size, so Why Doesn’t Venus Have a Magnetosphere? Maybe it Didn’t Get Smashed Hard Enough

For many reasons, Venus is sometimes referred to as “Earth’s Twin” (or “Sister Planet”, depending on who you ask). Like Earth, it is terrestrial (i.e. rocky) in nature, composed of silicate minerals and metals that are differentiated between an iron-nickel core and silicate mantle and crust. But when it comes to their respective atmospheres and magnetic fields, our two planets could not be more different.

For some time, astronomers have struggled to answer why Earth has a magnetic field (which allows it to retain a thick atmosphere) and Venus do not. According to a new study conducted by an international team of scientists, it may have something to do with a massive impact that occurred in the past. Since Venus appears to have never suffered such an impact, its never developed the dynamo needed to generate a magnetic field.

The study, titled “Formation, stratification, and mixing of the cores of Earth and Venus“, recently appeared in the scientific journal Earth and Science Planetary Letters. The study was led by Seth A. Jacobson of Northwestern University, and included members from the Observatory de la Côte d’Azur, the University of Bayreuth, the Tokyo Institute of Technology, and the Carnegie Institution of Washington.

For the sake of their study, Jacobson and his colleagues began considering how terrestrial planets form in the first place. According to the most widely-accepted models of planet formation, terrestrial planets are not formed in a single stage, but from a series of accretion events characterized by collisions with planetesimals and planetary embryos – most of which have cores of their own.

Recent studies on high-pressure mineral physics and on orbital dynamics have also indicated that planetary cores develop a stratified structure as they accrete. The reason for this has to do with how a higher abundance of light elements are incorporated in with liquid metal during the process, which would then sink to form the core of the planet as temperatures and pressure increased.

Such a stratified core would be incapable of convection, which is believed to be what allows for Earth’s magnetic field. What’s more, such models are incompatible with seismological studies that indicate that Earth’s core consists mostly of iron and nickel, while approximately 10% of its weight is made up of light elements – such as silicon, oxygen, sulfur, and others. It’s outer core is similarly homogeneous, and composed of much the same elements.

As Dr. Jacobson explained to Universe Today via email:

“The terrestrial planets grew from a sequence of accretionary (impact) events, so the core also grew in a multi-stage fashion. Multi-stage core formation creates a layered stably stratified density structure in the core because light elements are increasingly incorporated in later core additions. Light elements like O, Si, and S increasingly partition into core forming liquids during core formation when pressures and temperatures are higher, so later core forming events incorporate more of these elements into the core because the Earth is bigger and pressures and temperatures are therefore higher.

“This establishes a stable stratification which prevents a long-lasting geodynamo and a planetary magnetic field. This is our hypothesis for Venus. In the case of Earth, we think the Moon-forming impact was violent enough to mechanically mix the core of the Earth and allow a long-lasting geodynamo to generate today’s planetary magnetic field.”

To add to this state of confusion, paleomagnetic studies have been conducted that indicate that Earth’s magnetic field has existed for at least 4.2 billion years (roughly 340 million years after it formed). As such, the question naturally arises as to what could account for the current state of convection and how it came about. For the sake of their study, Jacobson and his team considering the possibility that a massive impact could account for this. As Jacobson indicated:

“Energetic impacts mechanically mix the core and so can destroy stable stratification. Stable stratification prevents convection which inhibits a geodynamo. Removing the stratification allows the dynamo to operate.”

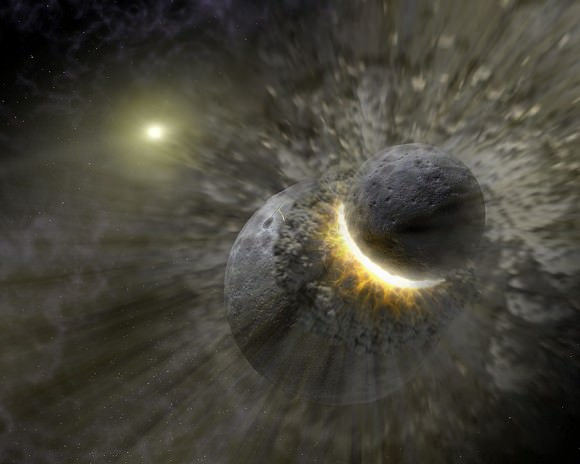

Basically, the energy of this impact would have shaken up the core, creating a single homogeneous region within which a long-lasting geodynamo could operate. Given the age of Earth’s magnetic field, this is consistent with the Theia impact theory, where a Mars-sized object is believed to have collided with Earth 4.51 billion years ago and led to the formation of the Earth-Moon system.

This impact could have caused Earth’s core to go from being stratified to homogeneous, and over the course of the next 300 million years, pressure and temperature conditions could have caused it to differentiate between a solid inner core and liquid outer core. Thanks to rotation in the outer core, the result was a dynamo effect that protected our atmosphere as it formed.

The seeds of this theory were presented last year at the 47th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in The Woodlands, Texas. During a presentation titled “Dynamical Mixing of Planetary Cores by Giant Impacts“, Dr. Miki Nakajima of Caltech – one of the co-authors on this latest study – and David J. Stevenson of the Carnegie Institution of Washington. At the time, they indicated that the stratification of Earth’s core may have been reset by the same impact that formed the Moon.

It was Nakajima and Stevenson’s study that showed how the most violent impacts could stir the core of planets late in their accretion. Building on this, Jacobson and the other co-authors applied models of how Earth and Venus accreted from a disk of solids and gas about a proto-Sun. They also applied calculations of how Earth and Venus grew, based on the chemistry of the mantle and core of each planet through each accretion event.

The significance of this study, in terms of how it relates to the evolution of Earth and the emergence of life, cannot be understated. If Earth’s magnetosphere is the result of a late energetic impact, then such impacts could very well be the difference between our planet being habitable or being either too cold and arid (like Mars) or too hot and hellish (like Venus). As Jacobson concluded:

“Planetary magnetic fields shield planets and life on the planet from harmful cosmic radiation. If a late, violent and giant impact is necessary for a planetary magnetic field then such an impact may be necessary for life.”

Looking beyond our Solar System, this paper also has implications in the study of extra-solar planets. Here too, the difference between a planet being habitable or not may come down to high-energy impacts being a part of the system’s early history. In the future, when studying extra-solar planets and looking for signs of habitability, scientists may very well be forced to ask one simple question: “Was it hit hard enough?”

Further Reading: Earth Science and Planetary Letters

Building Electronics That Can Work on Venus

The weather on Venus is like something out of Dante’s Inferno. The average surface temperature – 737 K (462 °C; 864 °F) – is hot enough to melt lead and the atmospheric pressure is 92 times that of Earth’s at sea level (9.2 MPa). For this reason, very few robotic missions have ever made it to the surface of Venus, and those that have did not last long – ranging from about 20 minutes to just over two hours.

Hence why NASA, with an eye to future missions, is looking to create robotic missions and components that can survive inside Venus’ atmosphere for prolonged periods of time. These include the next-generation electronics that researchers from NASA Glenn Research Center (GRC) recently unveiled. These electronics would allow a lander to explore Venus surface for weeks, months, or even years.

In the past, landers developed by the Soviets and NASA to explore Venus – as part of the Venera and Mariner programs, respectively – relied on standard electronics, which were based on silicon semiconductors. These are simply not capable of operating in the temperature and pressure conditions that exist on the surface of Venus, and therefore required that they have protective casings and cooling systems.

Naturally, it was only a matter of time before these protections failed and the probes stopped transmitting. The record was achieved by the Soviets with their Venera 13 probe, which transmitted for 127 minutes between its descent and landing. Looking ahead, NASA and other space agencies want to develop probes that can gather as much information as they can on Venus’s atmosphere, surface, and geological history before they time out.

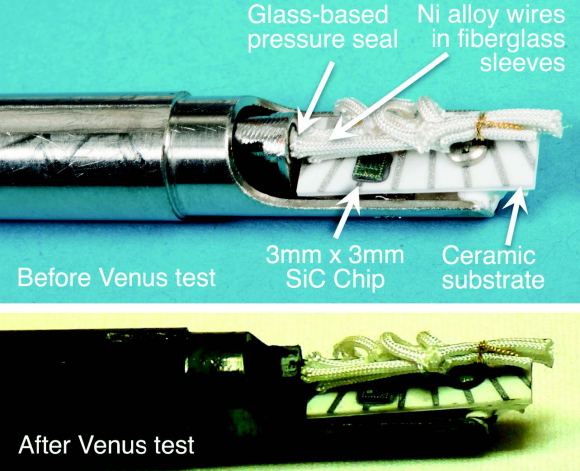

To do this, a team from NASA’s GRC has been working to develop electronics that rely on silcon carbide (SiC) semiconductors, which would be capable of operating at or above Venus’ temperatures. Recently, the team conducted a demonstration using the world’s first moderately-complex SiC-based microcircuits, which consisted of tens or more transistors in the form of core digital logic circuits and analog operation amplifiers.

These circuits, which would be used throughout the electronic systems of a future mission, were able to operate for up to 4000 hours at temperatures of 500 °C (932 °F) – effectively demonstrated that they could survive in Venus-like conditions for prolonged periods. These tests took place in the Glenn Extreme Environments Rig (GEER), which simulated Venus’ surface conditions, including both the extreme temperature and high pressure.

Back in April of 2016, the GRC team tested a SiC 12-transistor ring oscillator using the GEER for a period of 521 hours (21.7 days). During the test, they raised they subjected the circuits to temperatures of up to 460 °C (860 °F), atmospheric pressures of 9.3 MPa and supercritical levels of CO² (and other trace gases). Throughout the entire process, the SiC oscillator showed good stability and kept functioning.

This test was ended after 21 days due to scheduling reasons, and could have gone on much longer. Nevertheless, the duration constituted a significant world record, being orders of magnitude longer than any other demonstration or mission that has been conducted. Similar tests have shown that ring oscillator circuits can survive for thousands of hours at temperatures of 500 °C (932 °F) in Earth-air ambient conditions.

Such electronics constitute a major shift for NASA and space exploration, and would enable missions that were previously impossible. NASA’s Science Mission Direction (SMD) plans to incorporate SiC electronics on their Long-Life In-situ Solar System Explorer (LLISSE). A prototype is currently being developed for this low-cost concept, which would provide basic, but highly valuable scientific measures from the surface of Venus for months or longer.

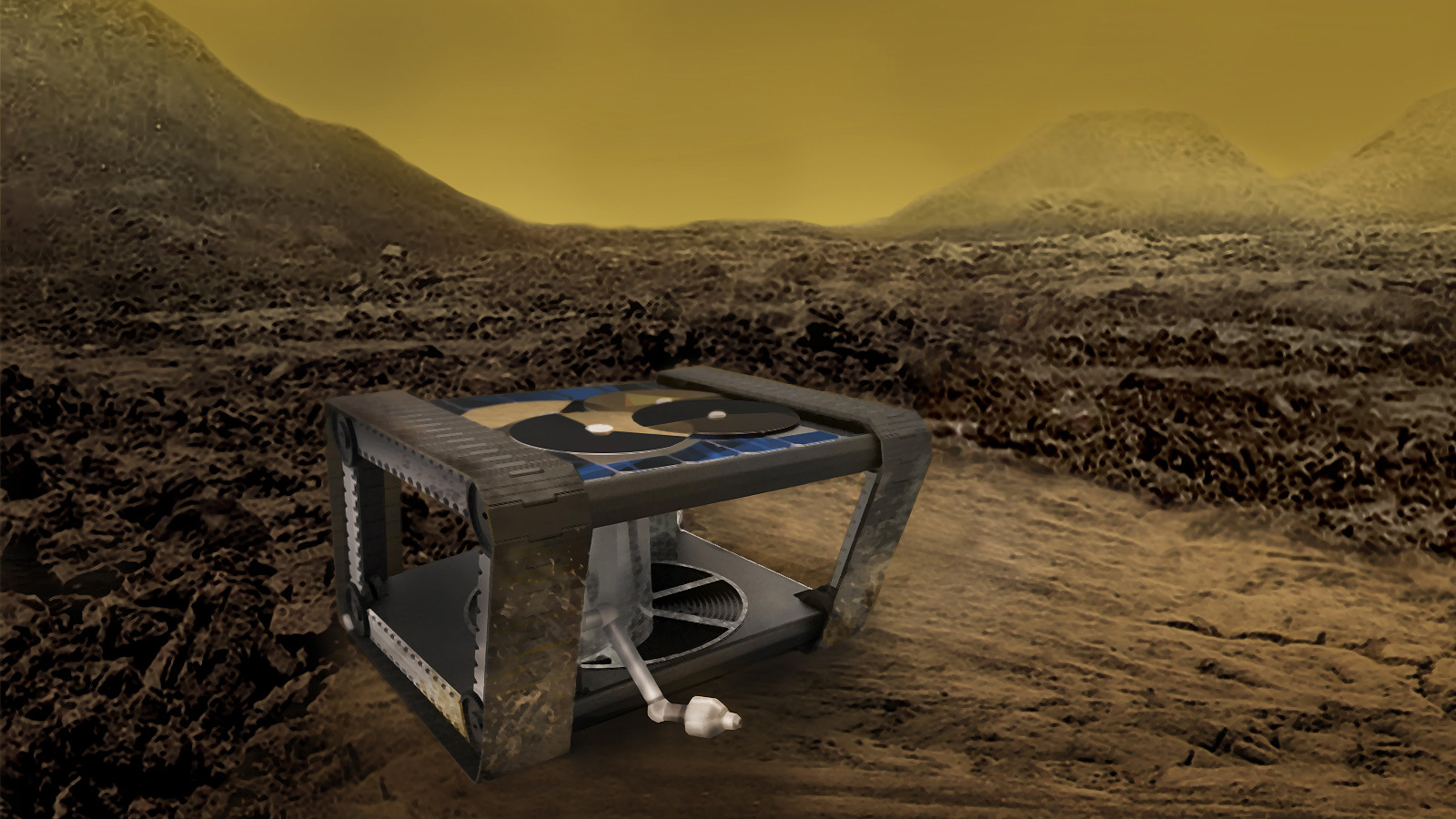

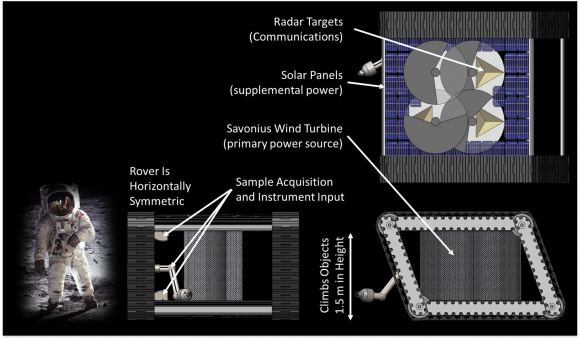

Other plans to build a survivable Venus explorer include the Automaton Rover for Extreme Environments (AREE), a “steampunk rover” concept that relies on analog components rather than complex electronic systems. Whereas this concepts seeks to do away with electronics entirely to ensure a Venus mission could operate indefinitely, the new SiC electronics would allow more complex rovers to continue operating in extreme conditions.

Beyond Venus, this new technology could also lead to new classes of probes capable of exploring within gas giants – i.e. Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune – where temperature and pressure conditions have been prohibitive in the past. But a probe that relies on a hardened shell and SiC electronic circuits could very well penetrate deep into the interior of these planets and reveal startling new things about their atmospheres and magnetic fields.

The surface of Mercury could also be accessible to rovers and landers using this new technology – even the day-side, where temperatures reach a high of 700 K (427 °C; 800 °F). Here on Earth, there are plenty of extreme environments that could now be explored with the help of SiC circuits. For example, drones equipped with SiC electronics could monitor deep-sea oil drilling or explore deep into the Earth’s interior.

There are also commercial applications involving aeronautical engines and industrial processors, where extreme heat or pressure traditionally made electronic monitoring impossible. Now such systems could be made “smart”, where they are capable of monitoring themselves instead of relying on operators or human oversight.

With extreme circuits and (someday) extreme materials, just about any environment could be explored. Maybe even the interior of a star!

Further Reading: NASA

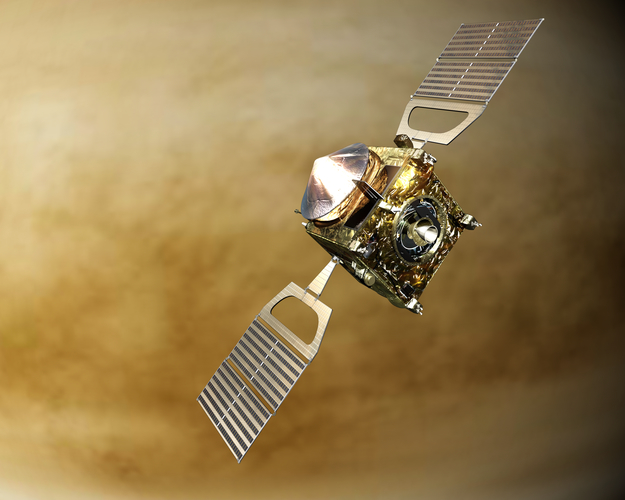

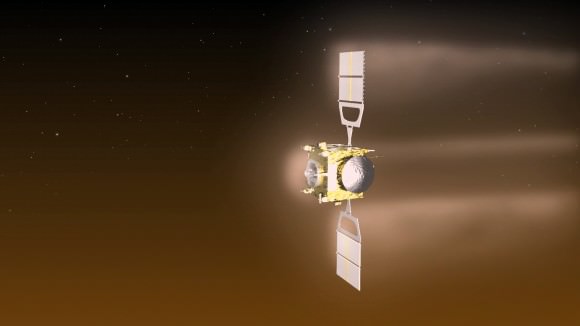

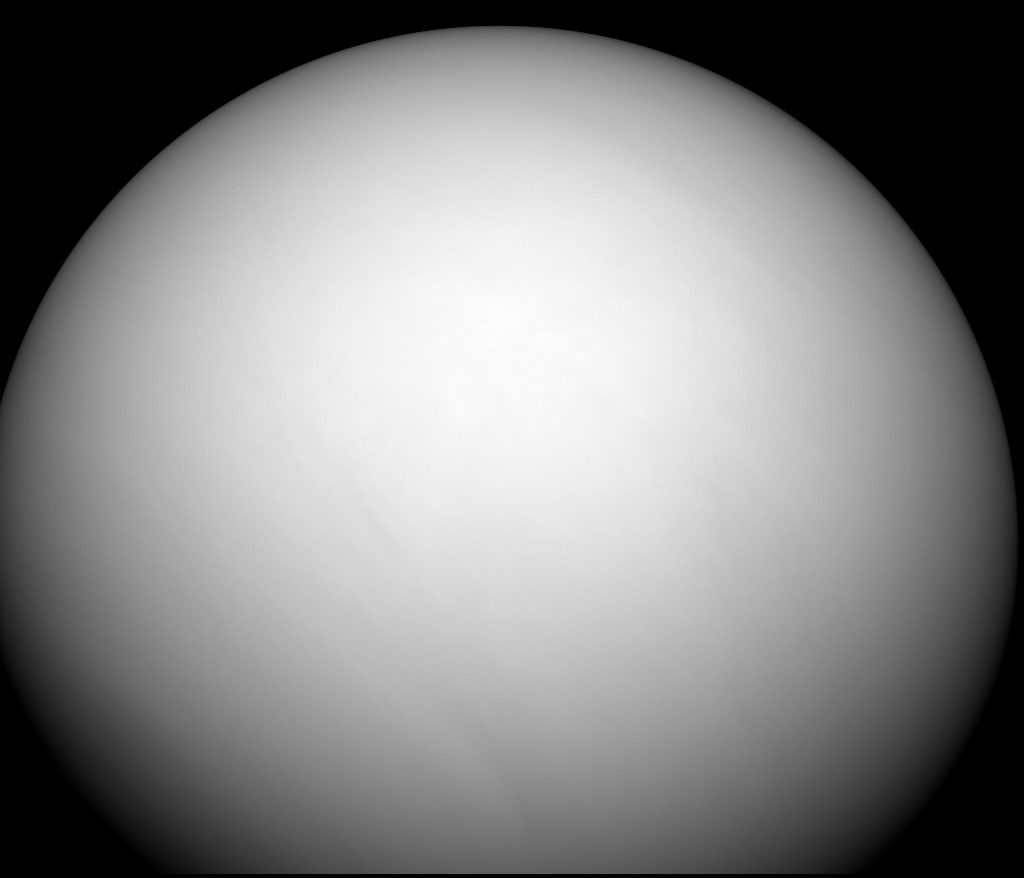

Venus Express Probe Reveals the Planet’s Mysterious Night Side

Venus’ atmosphere is as mysterious as it is dense and scorching. For generations, scientists have sought to study it using ground-based telescopes, orbital missions, and the occasional atmospheric probe. And in 2006, the ESA’s Venus Express mission became the first probe to conduct long-term observations of the planet’s atmosphere, which revealed much about its dynamics.

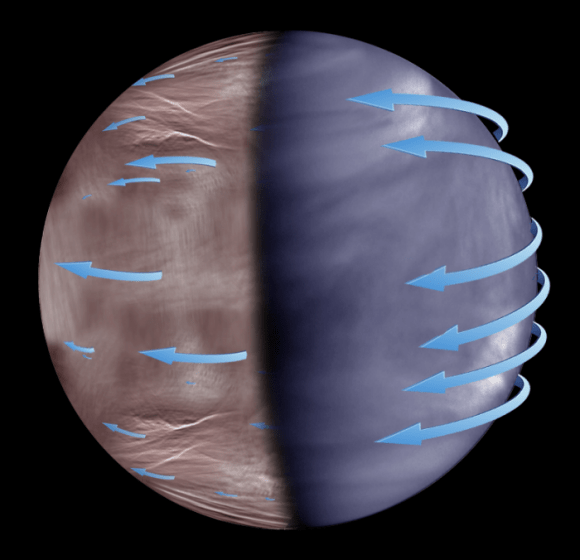

Using this data, a team of international scientists – led by researchers from the Japan Aerospace and Exploration Agency (JAXA) – recently conducted a study that characterized the wind and upper cloud patterns on the night side of Venus. In addition to being the first of its kind, this study also revealed that the atmosphere behaves differently on the night side, which was unexpected.

The study, titled “Stationary Waves and Slowly Moving Features in the Night Upper Clouds of Venus“, recently appeared in the scientific journal Nature Astronomy. Led by Javier Peralta, the International Top Young Fellow of JAXA, the team consulted data obtained by Venus Express’ suite of scientific instruments in order to study the planet’s previously-unseen cloud types, morphologies, and dynamics.

Whereas plenty of studies have been conducted of Venus’ atmosphere from soace, this was the first time that a study was not focused on the dayside of the planet. As Dr. Peralta explained in an ESA press statement:

“This is the first time we’ve been able to characterize how the atmosphere circulates on the night side of Venus on a global scale. While the atmospheric circulation on the planet’s dayside has been extensively explored, there was still much to discover about the night side. We found that the cloud patterns there are different to those on the dayside, and influenced by Venus’ topography.“

Since the 1960s, astronomers have been aware that Venus’ atmosphere behaves much differently that those of other terrestrial planets. Whereas Earth and Mars have atmospheres that co-rotate at approximately the same speed as the planet, Venus’ atmosphere can reach speeds of more than 360 km/h (224 mph). So while the planet takes 243 days to rotate once on its axis, the atmosphere takes only 4 days.

This phenomena, known as “super-rotation”, essentially means that the atmosphere moves over 60 times faster than the planet itself. In addition, measurements in the past have shown that the fastest clouds are located at the upper cloud level, 65 to 72 km (40 to 45 mi) above the surface. Despite decades of study, atmospheric models have been unable to reproduce super-rotation, which indicated that some of the mechanics were unknown.

As such, Peralta and his international team – which included researchers from the Universidad del País Vasco in Spain, the University of Tokyo, the Kyoto Sangyo University, the Center for Astronomy and Astrophysics (ZAA) at Berlin Technical University, and the Institute of Astrophysics and Space Planetology in Rome – chose to look at the unexplored side to see what they could find. As he described it:

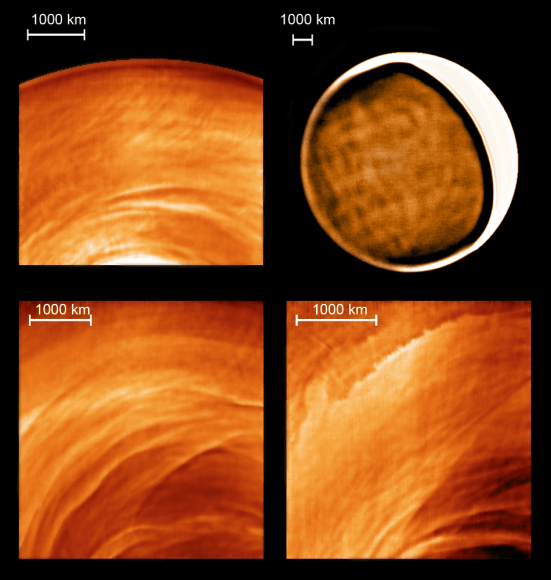

“We focused on the night side because it had been poorly explored; we can see the upper clouds on the planet’s night side via their thermal emission, but it’s been difficult to observe them properly because the contrast in our infrared images was too low to pick up enough detail.”

This consisted of observing Venus’ night side clouds with the probe’s Visible and Infrared Thermal Imaging Spectrometer (VIRTIS). The instrument gathered hundreds of images simultaneously and different wavelengths, which the team then combined to improve the visibility of the clouds. This allowed the team to see them properly for the first time, and also revealed some unexpected things about Venus’ night side atmosphere.

What they saw was that atmospheric rotation appeared to be more chaotic on the night side than what has been observed in the past on the dayside. The upper clouds also formed different shapes and morphologies – i.e. large, wavy, patchy, irregular and filament-like patterns – and were dominated by stationary waves, where two waves moving in opposite directions cancel each other out and create a static weather pattern.

The 3D properties of these stationary waves were also obtained by combining VIRTIS data with radio-science data from the Venus Radio Science experiment (VeRa). Naturally, the team was surprised to find these kinds of atmospheric behaviors since they were inconsistent with what has been routinely observed on the dayside. Moreover, they contradict the best models for explaining the dynamics of Venus’ atmosphere.

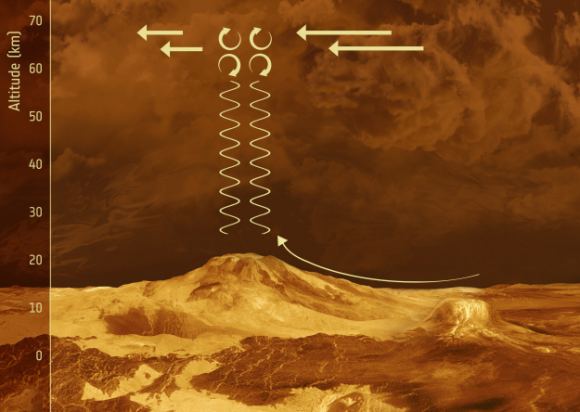

Known as Global Circulation Models (GCMs), these models predict that on Venus, super-rotation would occur in much the same way on both the dayside and the night side. What’s more, they noticed that stationary waves on the night side appeared to coincide with high-elevation features. As Agustin Sánchez-Lavega, a researcher from the University del País Vasco and a co-author on the paper, explained:

“Stationary waves are probably what we’d call gravity waves–in other words, rising waves generated lower in Venus’ atmosphere that appear not to move with the planet’s rotation. These waves are concentrated over steep, mountainous areas of Venus; this suggests that the planet’s topography is affecting what happens way up above in the clouds.“

This is not the first time that scientists have spotted a possible link between Venus’ topography and its atmospheric motion. Last year, a team of European astronomers produced a study that showed how weather patterns and rising waves on the dayside appeared to be directly connected to topographical features. These findings were based on UV images taken by the Venus Monitoring Camera (VMC) on board the Venus Express.

Finding something similar happening on the night side was something of a surprise, until they realized they weren’t the only ones to spot them. As Peralta indicated:

“It was an exciting moment when we realized that some of the cloud features in the VIRTIS images didn’t move along with the atmosphere. We had a long debate about whether the results were real–until we realised that another team, led by co-author Dr. Kouyama, had also independently discovered stationary clouds on the night side using NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility (IRTF) in Hawaii! Our findings were confirmed when JAXA’s Akatsuki spacecraft was inserted into orbit around Venus and immediately spotted the biggest stationary wave ever observed in the Solar System on Venus’ dayside.“

These findings also challenge existing models of stationary waves, which are expected to form from the interaction of surface wind and high-elevation surface features. However, previous measurements conducted by the Soviet-era Venera landers have indicated that surface winds might too weak for this to happen on Venus. In addition, the southern hemisphere, which the team observed for their study, is quite low in elevation.

And as Ricardo Hueso of the University of the Basque Country (and a co-author on the paper) indicated, they did not detect corresponding stationary waves in the lower cloud levels. “We expected to find these waves in the lower levels because we see them in the upper levels, and we thought that they rose up through the cloud from the surface,” he said. “It’s an unexpected result for sure, and we’ll all need to revisit our models of Venus to explore its meaning.”

From this information, it seems that topography and elevation are linked when it comes to Venus’ atmospheric behavior, but not consistently. So the standing waves observed on Venus’ night side may be the result of some other undetected mechanism at work. Alas, it seems that Venus’ atmosphere – in particular, the key aspect of super-rotation – still has some mysteries for us.

The study also demonstrated the effectiveness of combining data from multiple sources to get a more detailed picture of a planet’s dynamics. With further improvements in instrumentation and data-sharing (and perhaps another mission or two to the surface) we can expect to get a clearer picture of what is powering Venus’ atmospheric dynamics before long.

With a little luck, there may yet come a day when we can model the atmosphere of Venus and predict its weather patterns as accurately as we do those of Earth.

Further Reading: ESA, Nature Astronomy

NASA’s Plan to Explore Venus with a “SteamPunk” Rover

Venus is one hellish place! Aside from surface temperatures hot enough to melt lead – as high as 737 K (462 °C; 864 °F) – there’s also the sulfuric acid droplets and extreme pressure conditions (92 times that of Earth’s) to contend with! Because of these hostile conditions, exploring Venus’ surface and atmosphere has been an ongoing and significant challenge for space agencies.

Hence why NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) is looking at some truly innovative and unconventional ideas for future missions to Venus. One of them is the second-generation concept known as the Automaton Rover for Extreme Environments (AREE). By relying on clockwork mechanisms instead of electronics, this rover will be able to function on the surface of Venus for longer periods of time.

If deployed, this rover will build upon the accomplishments of the Soviet-era Venera and Vega programs, which were the only missions to ever successfully land on Venus’ hostile surface. Unfortunately, those probes that actually made it to the surface and landed safely only survived for 23 to 127 minutes before their electronics failed and they could no longer send back information.

This is the reality of operating machines on Venus, where the extreme temperatures will melt outer casings and sulfuric acid will corrode electronics. Hence why Jonathan Sauder, a mechatronics engineer at JPL, began tinkering with the idea of a clockwork rover. In this respect, he was inspired by mechanical computers, a time-honored concept that relies on levers and gears to make calculations rather than electronic components.

The earliest known example is the Antikythera mechanism, a device built by the ancient Greeks to predict astronomical phenomena. In 1642, French mathematician Blaise Pascal created what is considered to be the first mechanical calculator. Alternately known as the “Arithmetic Machine” and “Pascal Calculator“, Pascal is said to have invented this device to help his father reorganize the tax revenues for their province.

In the early 19th century, French weaver and merchant Joseph Marie Jacqaurd created the “Jacquard Loom“, a machine that relied on punch cards to turn out textiles in various patterns. And in 1822, English mathematician Charles Babbage began work on his “Difference Engine“, a machine that would automatically perform calculations and create error-free tables.

From these and other examples, Sauders and his team saw a possible solution to surviving Venus’ atmosphere. In essence, they proposed reverting back to an ancient practice of using analog gears to build a robot that could survive the most extreme environment within the Solar System. By relying on an entirely mechanical design and hardened metal structure, the AREE could theoretically survive for months or longer on Venus.

As Sauder explained in a recent NASA press statement:

“Venus is too inhospitable for kind of complex control systems you have on a Mars rover. But with a fully mechanical rover, you might be able to survive as long as a year.”

As a result, it would be able to send back far more information about Venus’ surface conditions and geological processes, which have remained something of a mystery for decades. These include (but are not limited to) why Venus has fewer volcanoes than Earth today – despite widespread evidence of volcanic activity early in its history – and the strange absorption patterns that have been seen in its upper atmosphere.

Sauder first proposed the concept back in 2015. In 2016, the concept was assessed as part of the NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) program, which opens itself to submissions every year for mission ideas. Along with twelve other proposals, AREE was selected for Phase I development and Sauder and his team were awarded $100,000 for a nine month period to assess the feasibility of their concept.

Beyond its processors, AREE would also rely on analog components for power. This would be necessary since solar cells cannot receive sunlight in Venus’ dense atmosphere. And a Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (MMRTG), which the Curiosity rover relies on for power, has complex electrical systems that would likely break down in Venus’s atmosphere.

Mobility is another challenge, and one which Sauder and his team also looked to an old idea to address. Basically, Venus’ rocky, craters surface is full of unknowns and will likely be very difficult to navigate. Sauder and his team therefore looked to World War I-era tanks treads as a solution. These vehicles were slow and lumbering, but were designed to traverse the difficult terrain of No Man’s Land, which was characterized by trenches and craters.

Originally, Sauder’s was inspired by Dutch artist Theo Jansen’s “Strandbeests“, a series of wood and canvas “robots” that relied on wind-driven gears to power their legs and walk along beaches. In the same vein, Sauder considered building a spider-like robot that used spindly legs to get around. However, this seemed too unstable for Venus’ rocky terrain, and treads were favored instead.

For communications, AREE would rely on another time-honored technology – Morse Code. This would involve an orbiting spacecraft pinging the rover using radar, while the rover would communicate by reflecting radar signals off of properly-shaped targets. Thanks to a rotating shutter, which would be positioned in front of the radar target, the rover would be able to turn the signal on and off to simulate dots and dashes.

If successful, this rover would be the first mission since the Cold War to explore the surface of Venus. As Evan Hilgemann, a JPL engineer working on high temperature designs for AREE, explained:

“When you think of something as extreme as Venus, you want to think really out there. It’s an environment we don’t know much about beyond what we’ve seen in Soviet-era images.”

Beyond Venus, such a probe would also be useful for exploring hostile environments on Mercury, within Jupiter’s radiation belt, interiors of gas giants, within volcanoes, and perhaps even the mantle of Earth. The AREE rover is currently in its second phase of NIAC development, and the team is working towards refining and prototyping parts of the concept.

In the future, Sauder and his team hope to expand the rover’s capabilities further and maybe equip it with a drill to collect geological samples. With the ability to function on the planet for up to a year, and the prospect of actual samples being obtained from the surface, scientists will be able to learn a great deal about Earth’s “Sister Planet”. This, in turn, could teach us much about the formation and evolution of rocky planets in our Solar System.

Be sure to check out this video of AREE concept, which features the team’s original spider-leg design:

NASA Plans to Send CubeSat To Venus to Unlock Atmospheric Mystery

From space, Venus looks like a big, opaque ball. Thanks to its extremely dense atmosphere, which is primarily composed of carbon dioxide and nitrogen, it is impossible to view the surface using conventional methods. As a result, little was learned about its surface until the 20th century, thanks to development of radar, spectroscopic and ultraviolet survey techniques.

Interestingly enough, when viewed in the ultraviolet band, Venus looks like a striped ball, with dark and light areas mingling next to one another. For decades, scientists have theorized that this is due to the presence of some kind of material in Venus’ cloud tops that absorbs light in the ultraviolet wavelength. In the coming years, NASA plans to send a CubeSat mission to Venus in the hopes of solving this enduring mystery.

The mission, known as the CubeSat UV Experiment (CUVE), recently received funding from the Planetary Science Deep Space SmallSat Studies (PSDS3) program, which is headquartered as NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. Once deployed, CUVE will determine the composition, chemistry, dynamics, and radiative transfer of Venus’ atmosphere using ultraviolet-sensitive instruments and a new carbon-nanotube light-gathering mirror.

The mission is being led by Valeria Cottini, a researcher from the University of Maryland who is also CUVE’s Principle Investigator (PI). In March of this year, NASA’s PSDS3 program selected it as one of 10 other studies designed to develop mission concepts using small satellites to investigate Venus, Earth’s moon, asteroids, Mars and the outer planets.

Venus is of particular interest to scientists, given the difficulties of exploring its thick and hazardous atmosphere. Despite the of NASA and other space agencies, what is causing the absorption of ultra-violet radiation in the planet’s cloud tops remains a mystery. In the past, observations have shown that half the solar energy the planet receives is absorbed in the ultraviolet band by the upper layer of its atmosphere – the level where sulfuric-acid clouds exist.

Other wavelengths are scattered or reflected into space, which is what gives the planet its yellowish, featureless appearance. Many theories have been advanced to explain the absorption of UV light, which include the possibility that an absorber is being transported from deeper in Venus’ atmosphere by convective processes. Once it reaches the cloud tops, this material would be dispersed by local winds, creating the streaky pattern of absorption.

The bright areas are therefore thought to correspond to regions that do not contain the absorber, while the dark areas do. As Cottini indicated in a recent NASA press release, a CubeSat mission would be ideal for investigating these possibilities:

“Since the maximum absorption of solar energy by Venus occurs in the ultraviolet, determining the nature, concentration, and distribution of the unknown absorber is fundamental. This is a highly-focused mission – perfect for a CubeSat application.”

Such a mission would leverage recent improvements in miniaturization, which have allowed for the creation of smaller, box-sized satellites that can do the same jobs as larger ones. For its mission, CUVE would rely on a miniaturized ultraviolet camera and a miniature spectrometer (allowing for analysis of the atmosphere in multiple wavelengths) as well as miniaturized navigation, electronics, and flight software.

Another key component of the CUVE mission is the carbon nanotube mirror, which is part of a miniature telescope the team is hoping to include. This mirror, which was developed by Peter Chen (a contractor at NASA Goddard), is made by pouring a mixture of epoxy and carbon nanotubes into a mold. This mold is then heated to cure and harden the epoxy, and the mirror is coated with a reflective material of aluminum and silicon dioxide.

In addition to being lightweight and highly stable, this type of mirror is relatively easy to produce. Unlike conventional lenses, it does not require polishing (an expensive and time-consuming process) to remain effective. As Cottini indicated, these and other developments in CubeSat technology could facilitate low-cost missions capable of piggy-backing on existing missions throughout the Solar System.

“CUVE is a targeted mission, with a dedicated science payload and a compact bus to maximize flight opportunities such as a ride-share with another mission to Venus or to a different target,” she said. “CUVE would complement past, current, and future Venus missions and provide great science return at lower cost.”

The team anticipates that in the coming years, the probe will be sent to Venus as part of a larger mission’s secondary payload. Once it reaches Venus, it will be launched and assume a polar orbit around the planet. They estimate that it would take CUVE one-and-a-half years to reach its destination, and the probe would gather data for a period of about six months.

If successful, this mission could pave the way for other low-cost, lightweight satellites that are deployed to other Solar bodies as part of a larger exploration mission. Cottini and her colleagues will also be presenting their proposal for the CUVE satellite and mission at the 2017 European Planetary Science Congress, which is being held from September 17th – 22nd in Riga, Latvia.

Further Reading: NASA