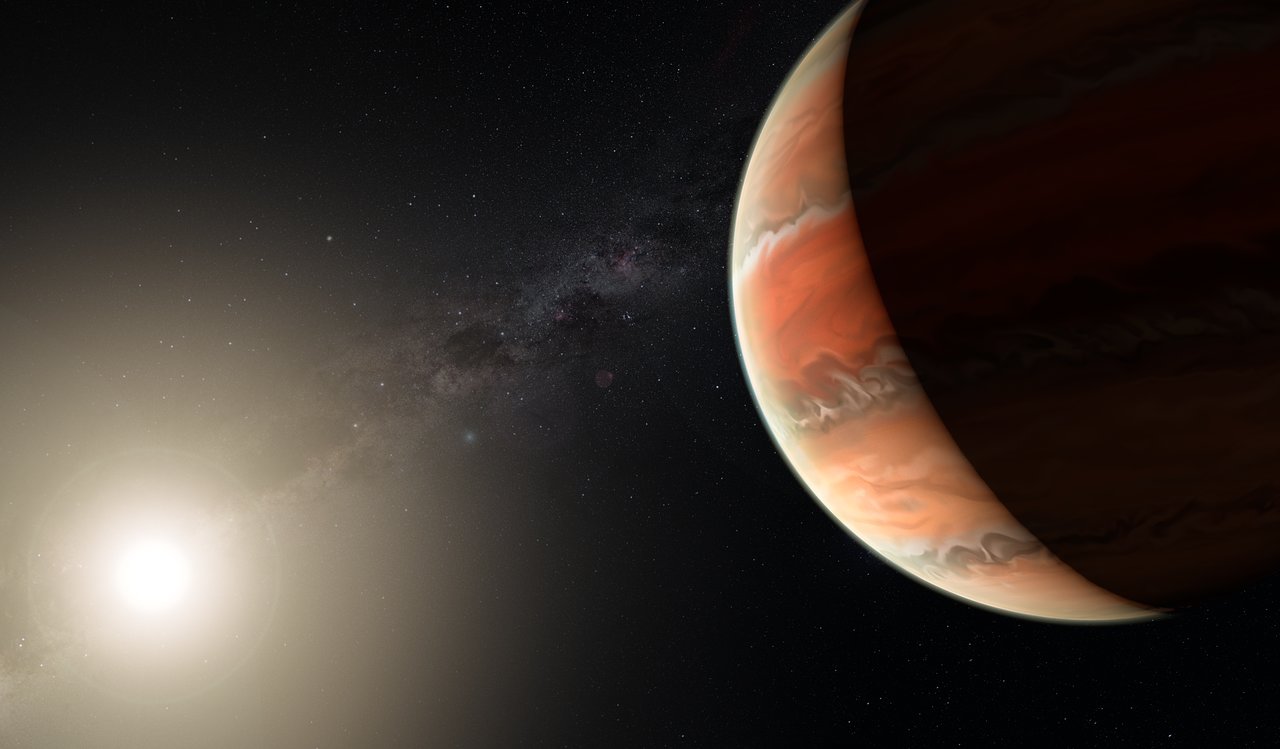

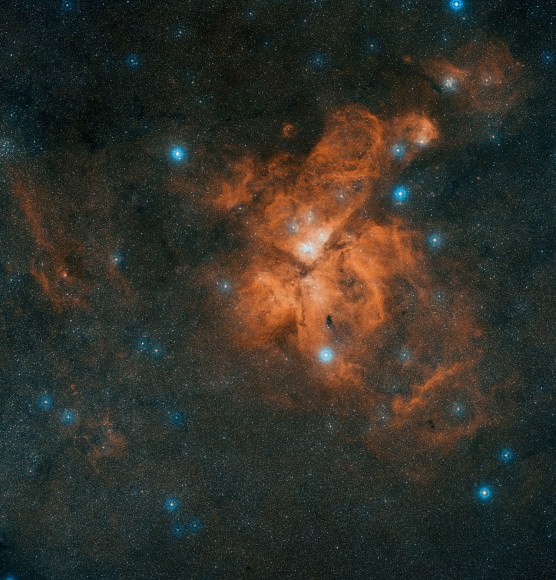

The hunt for exoplanets has turned up many fascinating case studies. For example, surveys have turned up many “Hot Jupiters”, gas giants that are similar in size to Jupiter but orbit very close to their suns. This particular type of exoplanet has been a source of interest to astronomers, mainly because their existence challenges conventional thinking about where gas giants can exist in a star system.

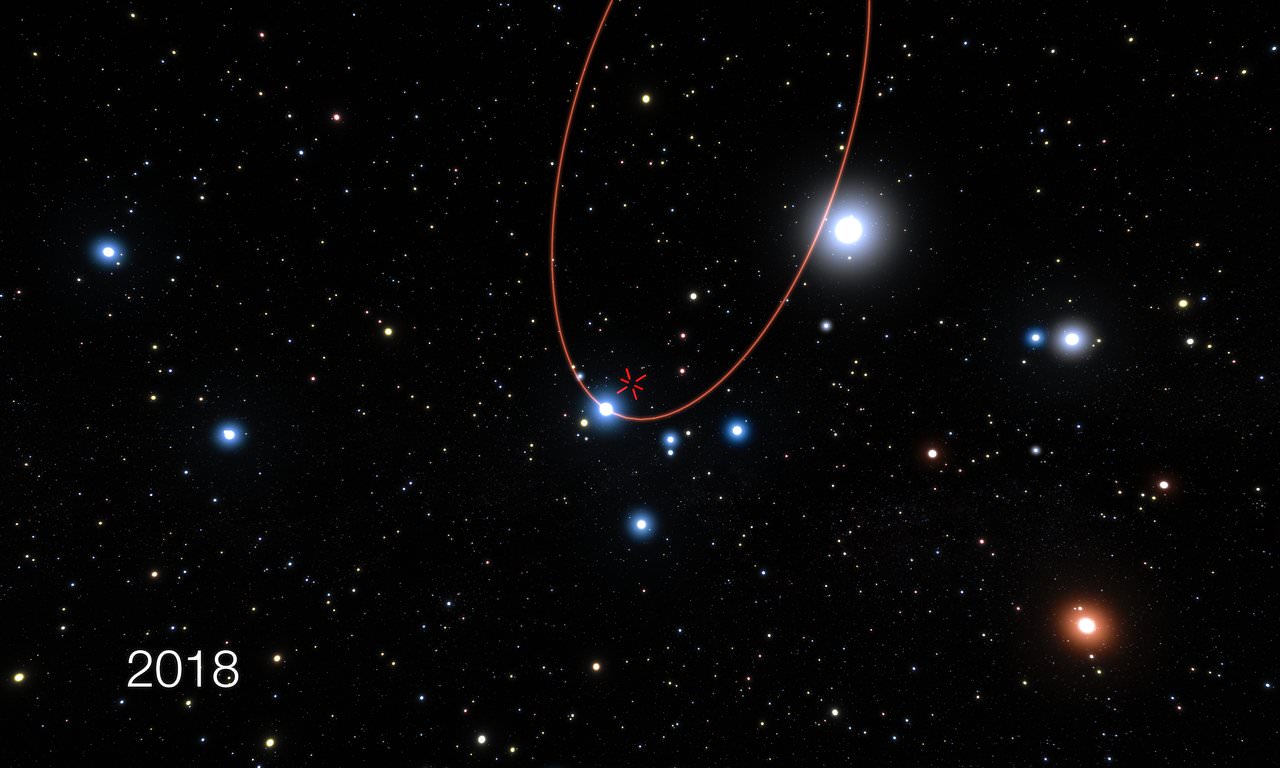

Hence why an international team led by researchers from the European Southern Observatory (ESO) used the Very Large Telescope (VLT) to get a better look at WASP-19b, a Hot Jupiter located 815 light-years from Earth. In the course of these observations, they noticed that the planet’s atmosphere contained traces of titanium oxide, making this the first time that this compound has been detected in the atmosphere of a gas giant.

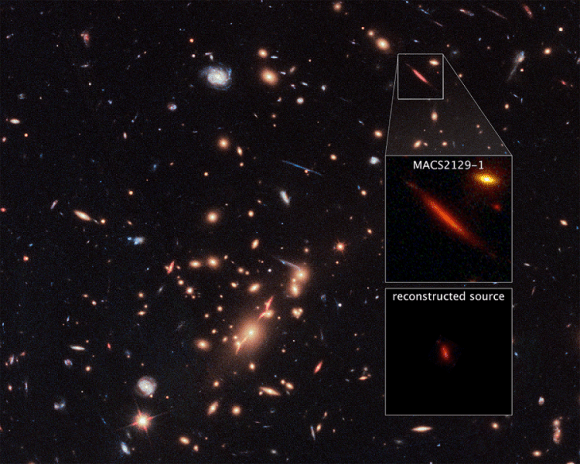

The study which describes their findings, titled “Detection of titanium oxide in the atmosphere of a hot Jupiter“, recently appeared in the science journal Nature. Led by Elyar Sedaghati – a recent graduate from the Technical University of Berlin and a fellow at the European Southern Observatory – the team used data collected by the VLT array over the course of a year to study WASP-19b.

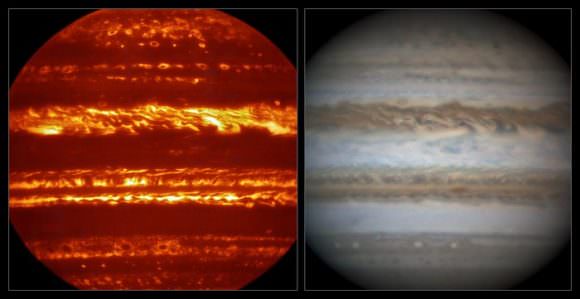

Like all Hot Jupiters, WASP-19b has about the same mass as Jupiter and orbits very close to its sun. In fact, its orbital period is so short – just 19 hours – that temperatures in its atmosphere are estimated to reach as high as 2273 K (2000 °C; 3632 °F). That’s over four times as hot as Venus, where temperatures are hot enough to melt lead! In fact, temperatures on WASP-19b are hot enough to melt silicate minerals and platinum!

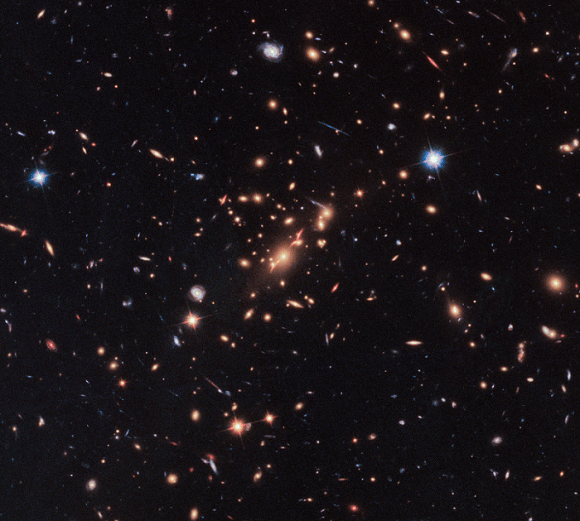

The study relied on the FOcal Reducer/low dispersion Spectrograph 2 (FORS2) instrument on the VLT, a multi-mode optical instrument capable of conducting imaging, spectroscopy and the study of polarized light (polarimetry). Using FORS2, the team observing the planet as it passed in front of its star (aka. made a transit), which revealed valuable spectra from its atmosphere.

After carefully analyzing the light that passed through its hazy clouds, the team was surprised to find trace amounts of titanium oxide (as well as sodium and water). As Elyar Sedaghati, who spent 2 years as a student with the ESO to work on this project, said of the discovery in an ES press release:

“Detecting such molecules is, however, no simple feat. Not only do we need data of exceptional quality, but we also need to perform a sophisticated analysis. We used an algorithm that explores many millions of spectra spanning a wide range of chemical compositions, temperatures, and cloud or haze properties in order to draw our conclusions.”

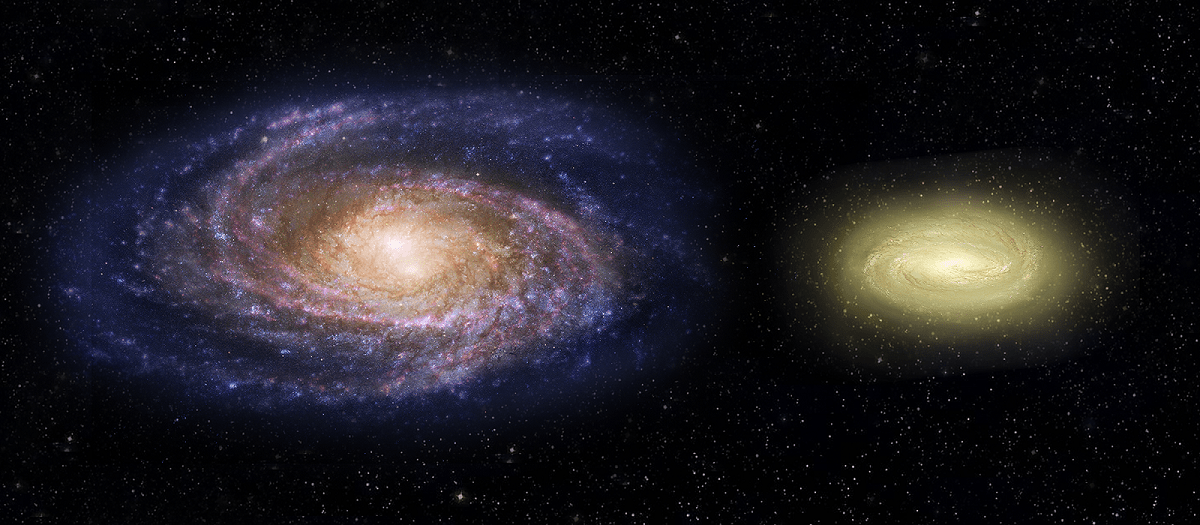

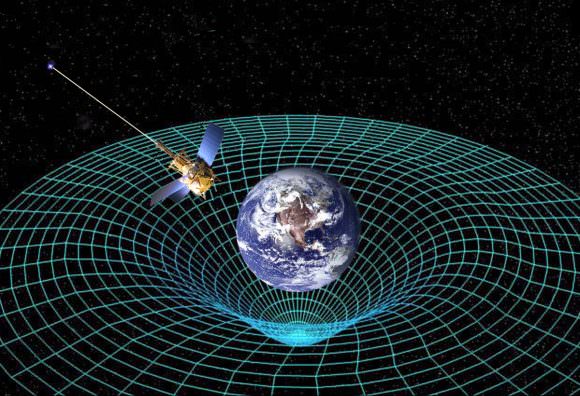

Titanium oxide is a very rare compound which is known to exist in the atmospheres of cool stars. In small quantities, it acts as a heat absorber, and is therefore likely to be partly responsible for WASP-19b experiencing such high temperatures. In large enough quantities, it can prevent heat from entering or escaping an atmosphere, causing what is known as thermal inversion.

This is a phenomena where temperatures are higher in the upper atmosphere and lower further down. On Earth, ozone plays a similar role, causing an inversion of temperatures in the stratosphere. But on gas giants, this is the opposite of what usually happens. Whereas Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune experience colder temperatures in their upper atmospheres, temperatures are much hotter closer to the core due to increases in pressure.

The team believes that the presence of this compound could have a substantial effect on the atmosphere’s temperature, structure and circulation. What’s more, the fact that the team was able to detect this compound (a first for exoplanet researchers) is an indication of how exoplanet studies are achieving new levels of detail. All of this is likely to have a profound impact on future studies of exoplanet atmospheres.

The study would also have not been possible were it not for the FORS2 instrument, which was added to the VLT array in recent years. As Henri Boffin, the instrument scientist who led the refurbishment project, commented:

“This important discovery is the outcome of a refurbishment of the FORS2 instrument that was done exactly for this purpose. Since then, FORS2 has become the best instrument to perform this kind of study from the ground.”

Looking ahead, it is clear that the detection of metal oxides and other similar substances in exoplanet atmospheres will also allow for the creation of better atmospheric models. With these in hand, astronomers will be able to conduct far more detailed and accurate studies on exoplanet atmospheres, which will allow them to gauge with greater certainty whether or not any of them are habitable.

So while this latest planet has no chance of supporting life – you’d have better luck finding ice cubes in the Gobi desert! – its discovery could help point the way towards habitable exoplanets in the future. On step closer to finding a world that could support life, or possibly that elusive Earth 2.0!