Greetings, fellow SkyWatchers! It’s going to be a great week to enjoy lunar studies, but why don’t we take a look at couple of other interesting objects, too? I think this would be the perfect opportunity to chase an asteroid! Not enough? Then get out your zombie hunting equipment and we’ll have a look at the “Demon Star”, too! Whenever you’re ready to learn a little more about the history and mystery of what’s out there, just meet me in the back yard…

Monday, October 22 – Something very special happened today in 2136 B.C. There was a solar eclipse, and for the very first time it was seen and recorded by Chinese astronomers. And probably a very good thing because in those days the royal astronomers were executed for failure to predict! Today is also the birthday of Karl Jansky. Born in 1905, Jansky was an American physicist as well as an electrical engineer. One of his pioneer discoveries was non-Earth-based radio waves at 20.5 MHz, a detection he made while investigating noise sources during 1931 and 1932. And, in 1975, Soviet Venera 9 was busy sending Earth the very first look at Venus’ surface.

Also today in 1966 Luna 12 was launched towards the Moon – as so shall we be. We’ll continue our lunar explorations as we look for the “three ring circus” of easily identified craters – Theophilus, Cyrillus, and Catherina – a challenging crater which spans 114 kilometers and goes below the lunar surface by 4730 meters. Are you ready to discover a very conspicuous lunar feature that was never officially named? Cutting its way across Mare Nectaris from Theophilus to shallow crater Beaumont in the south, you’ll see a long, thin, bright line. What you are looking at is an example of a lunar dorsum – nothing more than a wrinkle or low ridge. Chances are good that this ridge is just a “wave” in the lava flow that congealed when Mare Nectaris formed. This particular dorsa is quite striking tonight because of low illumination angle. Has it been named? Yes. It is unofficially known as “Dorsum Beaumont,” but by whatever name it is called, it remains a distinct feature you’ll continue to enjoy! Also to the far south along the terminator you will see Mutus, a small crater with black interior and bright, thin west wall crest. Angling further southwest from Mutus, look for a “bite” taken out of the terminator. This is crater Manzinus.

Tuesday, October 23 – Now it’s time to look for Mare Vaporum – “The Sea of Vapors” – on the southwest shore of Mare Serenitatis. Formed from newer lava flow inside an old crater, this lunar sea is edged to its north by the mighty Apennine Mountains. On its northeastern edge, look for the now washed-out Haemus Mountains. Can you see where lava flow has reached them? This lava has come from different time periods and the slightly different colorations are easy to spot even with binoculars.

Further south and edged by the terminator is Sinus Medii – the “Bay in the Middle” of the visible lunar surface. Central on the terminator, and the adopted “center” of the lunar disc, this the point from which latitude and longitude are measured. This smooth plain may look small, but it covers about as much area as the states of Massachusetts and Connecticut combined. During full daylight temperatures in Sinus Medii can reach up to 212 degrees! On a curious note, in 1930 Sinus Medii was chosen by Edison Petitt and Seth Nicholson for a surface temperature measurement at full Moon. Experiments of this type were started by Lord Rosse as early as 1868, but on this occasion Petit and Nicholson found the surface to be slightly warmer than boiling water. Around a hundred years after Rosse’s attempt, Surveyor 6 successfully landed in Sinus Medii on November 9, 1967, and became the very first probe to “lift off” from the lunar surface.

Wednesday, October 24 – Today in 1851, a busy astronomer was at the eyepiece as William Lassell discovered Uranus’ moons Ariel and Umbriel. Although this is far beyond backyard equipment, we can have a look at that distant world. While Uranus’ small, blue/green disc isn’t exactly the most exciting thing to see in a small telescope or binoculars, the very thought that we are looking at a planet that’s over 18 times further from the Sun than we are is pretty impressive! Usually holding close to a magnitude 6, we watch as the tilted planet orbits our nearest star once every 84 years. Its atmosphere is composed of hydrogen, helium and methane, yet pressure causes about a third of this distant planet to behave as a liquid. Larger telescopes may be able to discern a few of Uranus’ moons, for Titania (the brightest) is around magnitude 14.

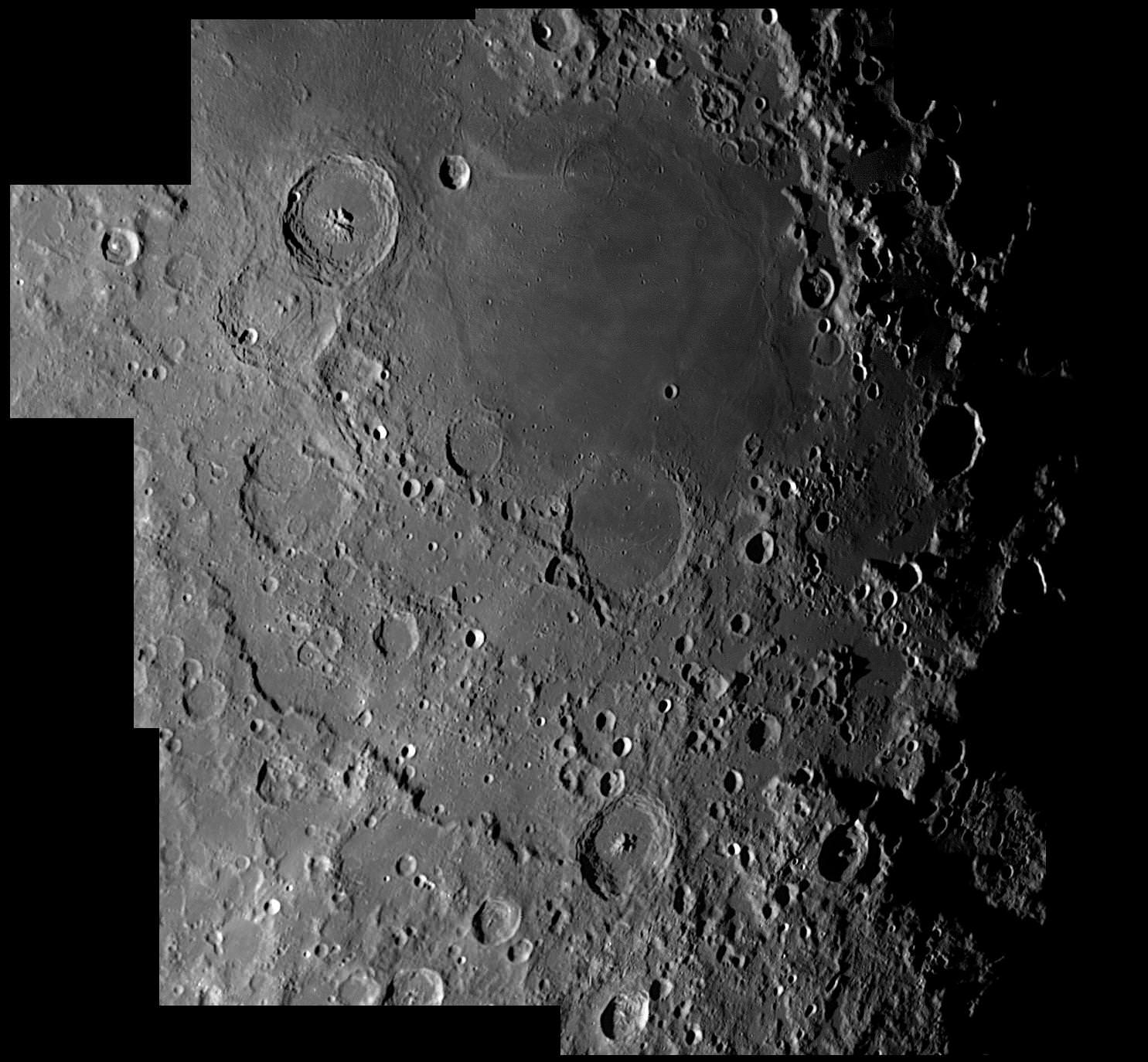

Let’s begin our lunar studies tonight with a deeper look at the “Sea of Rains.” Our mission is to explore the disclosure of Mare Imbrium, home to Apollo 15. Stretching out 1123 kilometers over the Moon’s northwest quadrant, Imbrium was formed around 38 million years ago when a huge object impacted the lunar surface creating a gigantic basin.

The basin itself is surrounded by three concentric rings of mountains. The most distant ring reaches a diameter of 1300 kilometers and involves the Montes Carpatus to the south, the Montes Ap-enninus southwest, and the Caucasus to the east. The central ring is formed by the Montes Alpes, and the innermost has long been lost except for a few low hills which still show their 600 kilometer diameter pattern through the eons of lava flow. Originally the impact basin was believed to be as much as 100 kilometers deep. So devastating was the event that a Moon-wide series of fault lines appeared as the massive strike shattered the lunar lithosphere. Imbrium is also home to a huge mascon, and images of the far side show areas opposite the basin where seismic waves traveled through the interior and shaped its landscape. The floor of the basin rebounded from the cataclysm and filled in to a depth of around 12 kilometers. Over time, lava flow and regolith added another five kilometers of material, yet evidence remains of the ejecta which was flung more than 800 kilometers away, carving long runnels through the landscape.

Thursday, October 25 – And who was watching the planets in 1671? None other than Giovanni Cassini – because he’d just discovered Saturn’s moon Iapetus.

Tonight let’s discover our own Moon as we take a look at Mare Insularum, the “Sea Of Islands”. Ir will be partially revealed tonight as one of the most prominent of lunar craters – Copernicus – guides the way. While only a small section of this reasonably young mare is now visible southwest of Copernicus, the lighting will be just right to spot its many different colored lava flows. To the northeast is a lunar club challenge: Sinus Aestuum. Latin for the Bay of Billows, this mare-like region has an approximate diameter of 290 kilometers, and its total area is about the size of the state of New Hampshire. Containing almost no features, this area is low albedo and provides very little surface reflectivity. Can you see any of Copernicus’ splash rays beginning to appear yet?

Today is the birthday of Henry Norris Russell. Born in 1877, Russell was the American leader in establishing the modern field of astrophysics. As the namesake for the American Astronomical Society’s highest award (for lifetime contributions to the field), Mr. Russell is the “R” in HR diagrams, along with Mr. Hertzsprung. This work was first used in a 1914 paper, published by Russell.

Tonight let’s have a look at a star that resides right in the middle of the HR diagram as we have a look Beta Aquarii.

Named Sadal Suud (“Luck of Lucks”), this star of spectral type G is around 1030 light-years distant from our solar system and shines 5800 times brighter than our own Sun. The main sequence beauty also has two 11th magnitude optical companions. The one closest to Sadal Suud was discovered by John Herschel in 1828, while the further star was reported by S.W. Burnham in 1879.

Friday, October 26 – It’s big. It’s bright. It’s the Moon! Look for a small, but very bright, small crater that you just can’t miss… Kepler! This great landmark crater named for Johannes Kepler only spans 32 kilometers, but drops to a deep 2750 meters below the surface. It’s a class I crater that’s a geological hotspot! As the very first lunar crater to be mapped by the U.S. Geological Survey, the area around Kepler contains many smooth lava domes reaching no more than 30 meters above the plains. The crater rim is very bright, consisting mostly of a pale rock called anorthosite. The “lines” extending from Kepler are fragments that were splashed out and flung across the lunar surface when the impact occurred. According to records, in 1963 a glowing red area was spotted near Kepler and extensively photographed. Normally one of the brightest regions of the Moon, the brightness value at the time nearly doubled! Although it was rather exciting, scientists later determined the phenomenon was caused by high energy particles from a solar flare reflecting from Kepler’s high albedo surface – a sharp contrast from the dark mare composed primarily of dark minerals of low reflectivity (albedo) such as iron and magnesium. The region is also home to features known as “domes” – similar to Earth’s shield volcanoes – seen between the crater and the Carpathian Mountains. In the days ahead all details around Kepler will be lost, so take this opportunity to have a good look at one awesome small crater.

This evening we are once again going to study a single star, which will help you become acquainted with the constellation of Perseus. Its formal name is Beta Persei and it is the most famous of all eclipsing variable stars. Tonight, let’s identify Algol and learn all about the “Demon Star.”

Ancient history has given this star many names. Associated with the mythological figure Perseus, Beta was considered to be the head of Medusa the Gorgon, and was known to the Hebrews as Rosh ha Satan or “Satan’s Head.” 17th century maps labeled Beta as Caput Larvae, or the “Specter’s Head,” but it is from the Arabic culture that the star was formally named. They knew it as Al Ra’s al Ghul, or the “Demon’s Head,” and we know it as Algol. Because these medieval astronomers and astrologers associated Algol with danger and misfortune, we are led to believe that Beta’s strange visual variable properties were noted throughout history.

Italian astronomer Geminiano Montanari was the first to record that Algol occasionally “faded,” and its methodical timing was cataloged by John Goodricke in 1782, who surmised that it was being partially eclipsed by a dark companion orbiting it. Thus was born the theory of the “eclipsing binary” and this was proved spectroscopically in 1889 by H. C. Vogel. At 93 light-years away, Algol is the nearest eclipsing binary of its kind, and is treasured by the amateur astronomer because it requires no special equipment to easily follow its stages. Normally Beta Persei holds a magnitude of 2.1, but approximately every three days it dims to magnitude 3.4 and gradually brightens again. The entire eclipse only lasts about 10 hours!

Although Algol is known to have two additional spectroscopic companions, the true beauty of watching this variable star is not telescopic – but visual. The constellation of Perseus is well placed this month for most observers and appears like a glittering chain of stars that lie between Cassiopeia and Andromeda. To help further assist you, re-locate last week’s study star, Gamma Andromedae (Almach) east of Algol. Almach’s visual brightness is about the same as Algol’s at maximum.

Saturday, October 27 – Tonight let’s skip the Moon and hunt down an asteroid! We’ll be locating Vesta which will be cruising along the southern border of Taurus, just about a handspan north/northwest of Betelgeuse. However, since asteroids are always on the move, the position will need to be calculated for your area, so use your local planetarium programs to get an accurate map. When you’re ready, let’s talk…

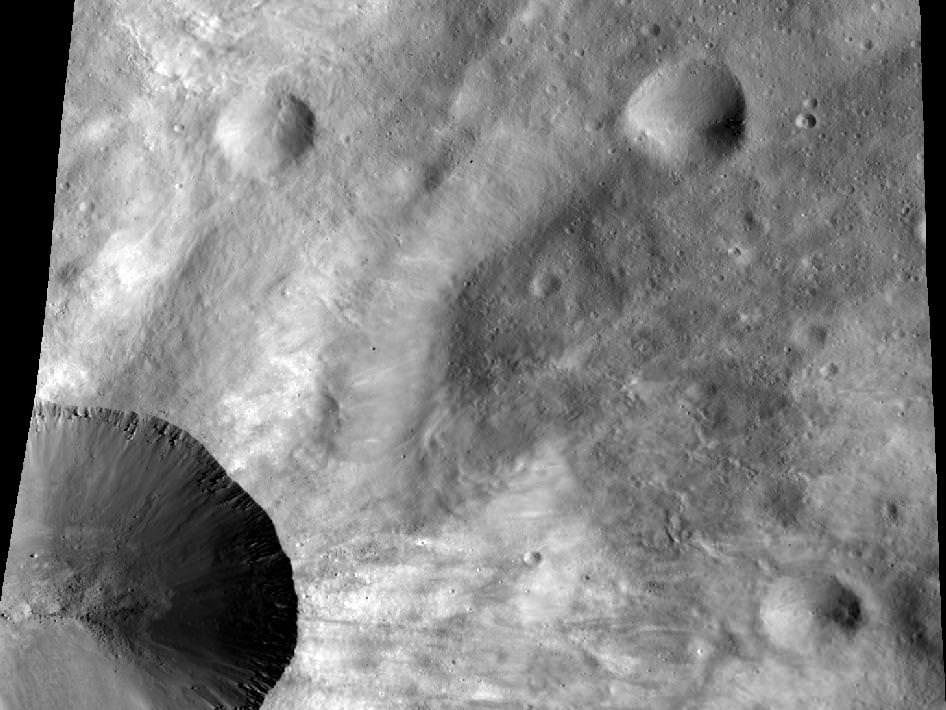

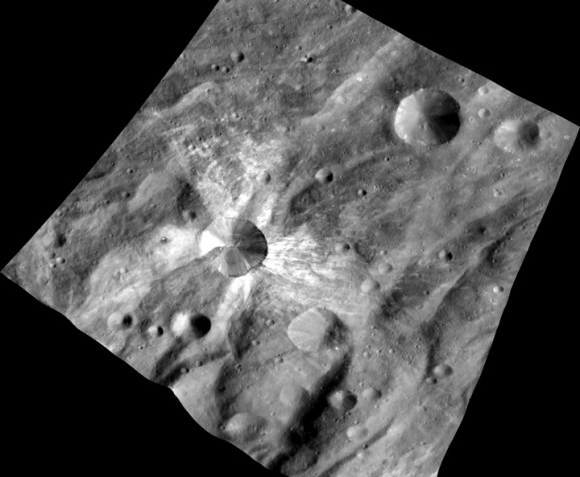

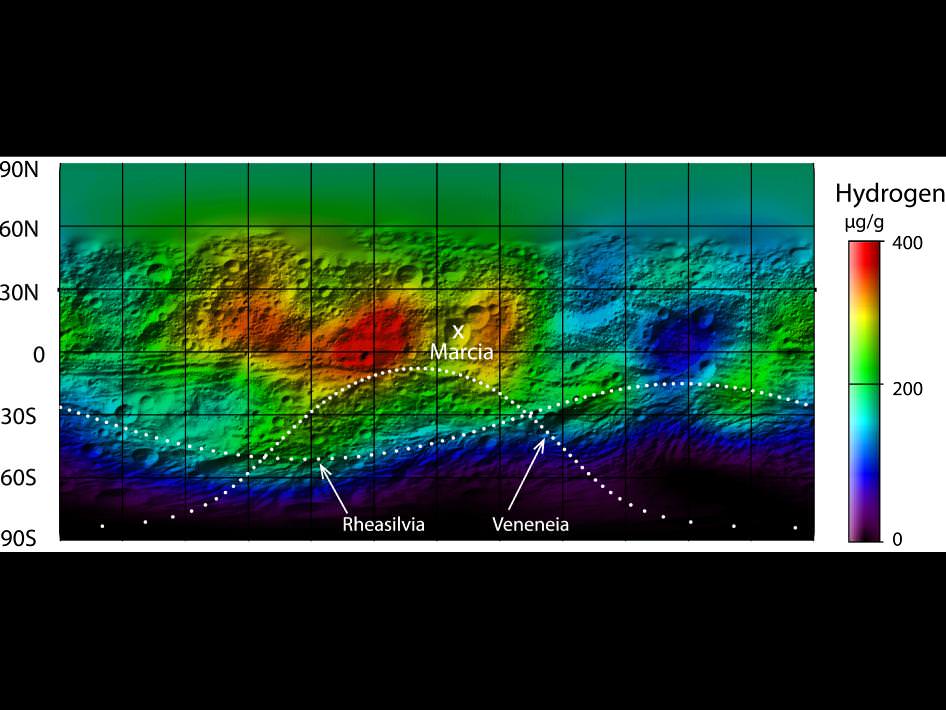

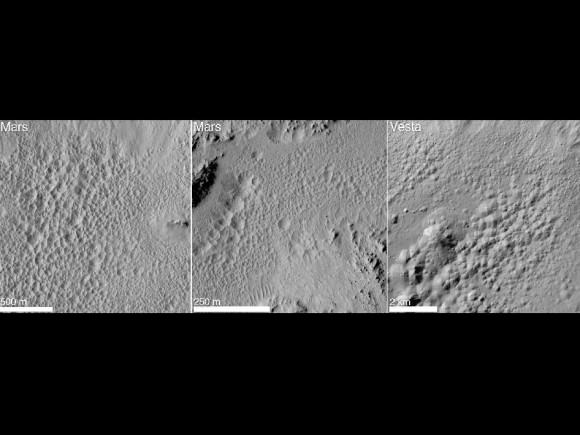

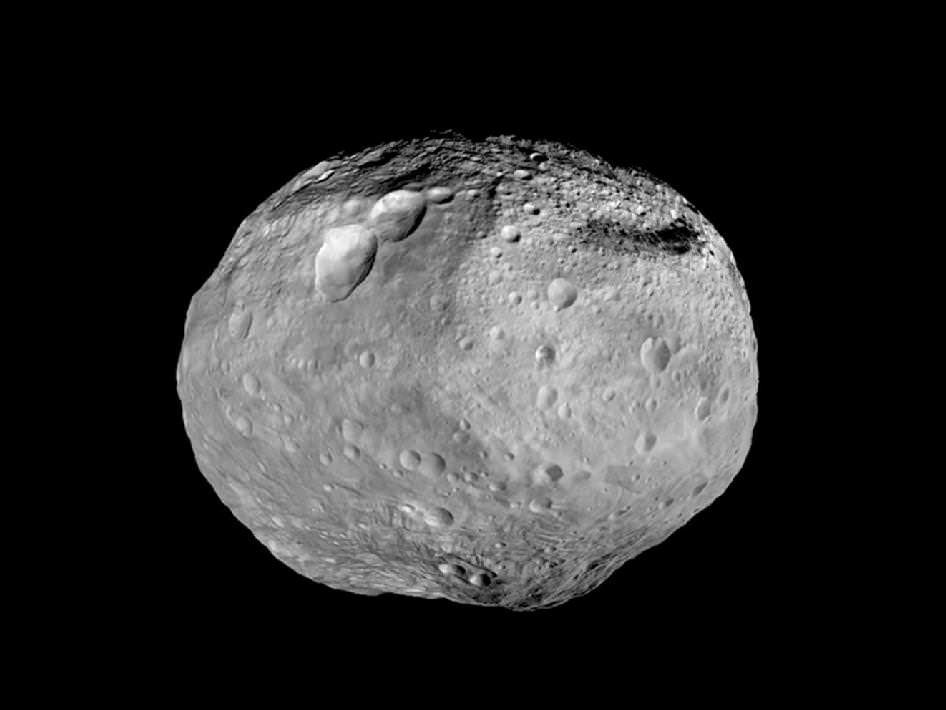

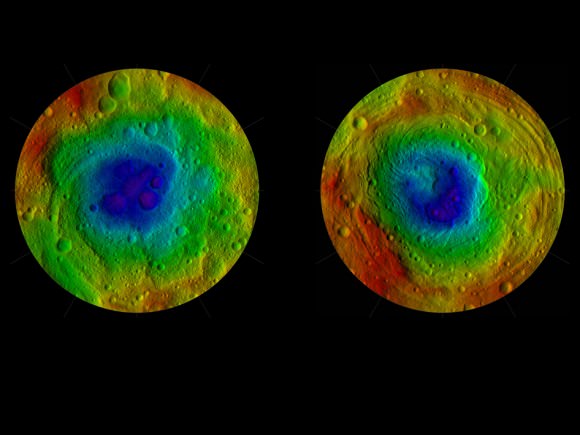

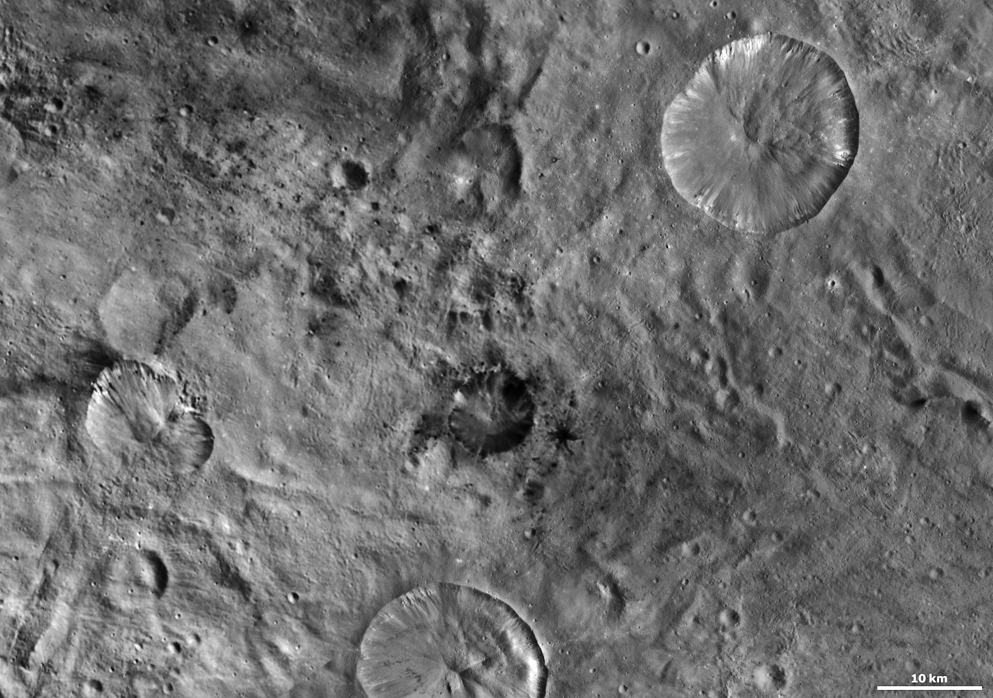

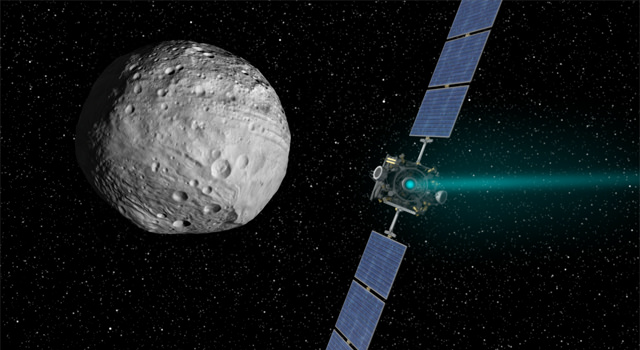

Asteroid Vesta is considered to be a minor planet since its approximate diameter is 525 km (326 miles), making it slightly smaller in size than the state of Arizona. Vesta was discovered on March 29, 1807 by Heinrich Olbers and it was the fourth such “minor planet” to be identified. Olbers’ discovery was fairly easy because Vesta is the only asteroid bright enough at times to be seen unaided from Earth. Why? Orbiting the Sun every 3.6 years and rotating on its axis in 5.24 hours, Vesta has an albedo (or surface reflectivity) of 42%. Although it is about 220 million miles away, pumpkin-shaped Vesta is the brightest asteroid in our solar system because it has a unique geological surface. Spectroscopic studies show it to be basaltic, which means lava once flowed on the surface. (Very interesting, since most asteroids were once thought to be rocky fragments left-over from our forming solar system!)

Studies by the Hubble telescope have confirmed this, as well as shown a large meteoric impact crater which exposed Vesta’s olivine mantle. Debris from Vesta’s collision then set sail away from the parent asteroid. Some of the debris remained within the asteroid belt near Vesta to become asteroids themselves with the same spectral pyroxene signature, but some escaped through the “Kirkwood Gap” created by Jupiter’s gravitational pull. This allowed these small fragments to be kicked into an orbit that would eventually bring them “down to Earth.” Did one make it? Of course! In 1960 a piece of Vesta fell to Earth and was recovered in Australia. Thanks to Vesta’s unique properties, the meteorite was definitely classified as once being a part of our third largest asteroid. Now, that we’ve learned about Vesta, let’s talk about what we can see from our own backyards.

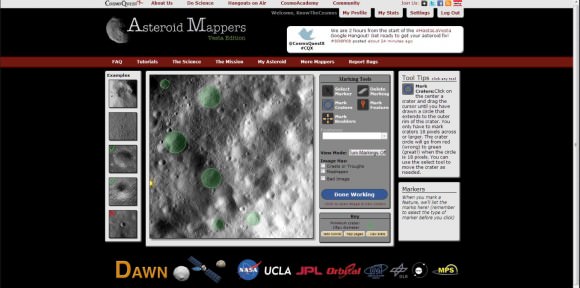

As you can discern from images, even the Hubble Space Telescope doesn’t give incredible views of this bright asteroid. What we will be able to see in our telescopes and binoculars will closely resemble a roughly magnitude 7 “star,” and it is for that reason that I strongly encourage you to visit Heavens Above, follow the instructions and print yourself a detailed map of the area. When you locate the proper stars and the asteroid’s probable location, mark physically on the map Vesta’s position. Keeping the same map, return to the area a night or two later and see how Vesta has moved since your original mark. Since Vesta will stay located in the same area for awhile, your observations need not be on a particular night, but once you learn how to observe an asteroid and watch it move – you’ll be back for more!

Sunday, October 28 – Today in 1971, Great Britain launched its first satellite – Prospero.

Tonight we’ll launch our journey along the southern shore of Mare Humorum and identify ancient crater Vitello. Notice how this delicate ring resembles earlier study Gassendi on the opposite shore. Its slopes have been crushed by the impact that formed crater Lee to its west. As you begin to circle around Mare Humorum and start northward again, you’ll be traveling along the Rupes Kelvin – ending in the spearhead formation of Promentorium Kelvin. Here again is another extremely old feature, a triangular mountainous cape born in the pre-Imbrian period and as much as 4 billion years old. It could be as long as 41 miles and about as wide as 21 miles, but its height is impossible to judge.

Take a breath now, and we’ll look for two more dark patches to guide us on. South of Mare Humorum is darker Paulus Epidemiarum eastward and paler Lacus Excellentiae westward. To their south you will see a complex cojoined series of craters we’ll take a closer look at – Hainzel and Mee. Hainzel was named for Tycho Brahe’s assistant and measures about 70 kilometers in length and sports several various interior wall structures. Power up and look. Hainzel’s once high walls were obliterated on the north-east by the strike that caused Hainzel C and to the north by impact which caused the formation of Hainzel A. To its basic south is eroded Mee – named for a Scottish astronomer. While Crater Mee doesn’t appear to be much more than simple scenery, it spans 172 kilometers and is far older than Hainzel. While you can spot it easily in binoculars, close telescope inspection shows how the crater is completely deformed by Hainzel. Its once high walls have collapsed to the northwest and its floor is destroyed. Can you spot small impact crater Mee E on the northern edge?

Until next week, wishing you clear and steady skies!