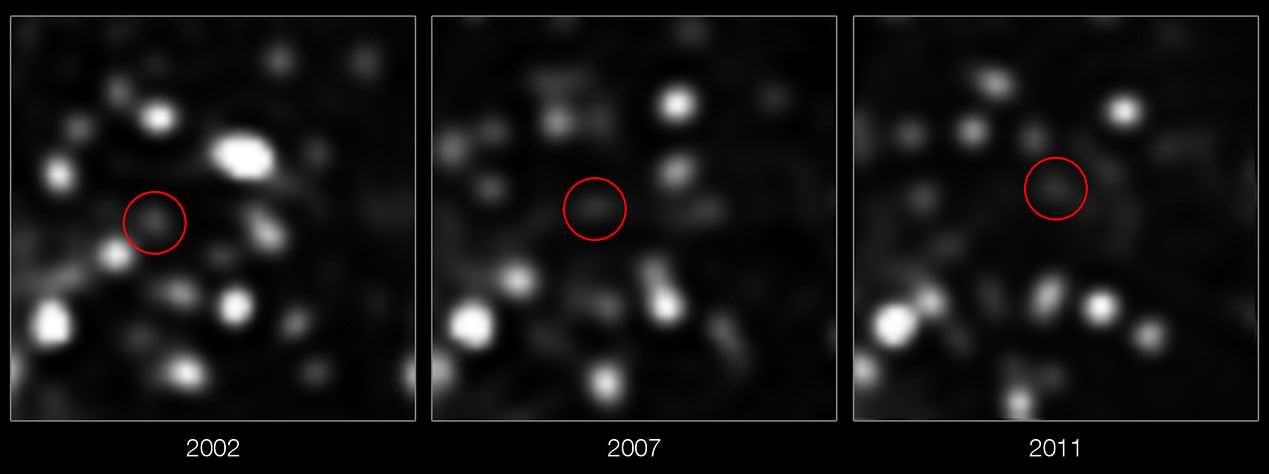

If you thought all was reasonably quiet at the center of the Milky Way, you’d be wrong. Of course, you knew there was a black hole waiting… but did you know the ESO’s Very Large Telescope has seen a cloud of gas being ripped apart by its influence? Thanks to new observations, we’re able to see – in real time – a gaseous region so stretched that its leading edge has reached the event horizon and it’s retreating from the black hole at more than 10 million km/h while the trailing end is still falling inward!

Just two years ago, the VLT observed a gas cloud several times the mass of Earth making haste towards the Milky Way’s central black hole… an oblivion which dwarfs the cloud by about a trillion times. Right now the plucky cloud has reached its closest approach and “spaghettification” has began. The vaporous vagabond is being stretched out of proportion by the black hole’s gravitational field.

“The gas at the head of the cloud is now stretched over more than 160 billion kilometres around the closest point of the orbit to the black hole. And the closest approach is only a bit more than 25 billion kilometres from the black hole itself — barely escaping falling right in,” explains Stefan Gillessen (Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, Garching, Germany) who led the observing team. “The cloud is so stretched that the close approach is not a single event but rather a process that extends over a period of at least one year.”

At this point, the gas cloud is becoming so thin that its light is difficult to detect. However, by using the SINFONI instrument on the VLT, researchers took 20 hours of exposure time with the integral field spectrometer and were able to measure the velocity of various regions of the gas cloud as it blazes by the black hole.

“The most exciting thing we now see in the new observations is the head of the cloud coming back towards us at more than 10 million km/h along the orbit — about 1% of the speed of light,” adds Reinhard Genzel, leader of the research group that has been studied this region for nearly twenty years. “This means that the front end of the cloud has already made its closest approach to the black hole.”

Where the gas cloud originated is anyone’s guess – but there are suggestions. Possibilities include jets from the galactic center, or stellar winds from orbiting stars. There may have once been a star in the center of the cloud, and the gas may have been a product of its winds or even a protoplanetary disk. In any circumstance, these new observations help to sort out the variety of possibilities.

“Like an unfortunate astronaut in a science fiction film, we see that the cloud is now being stretched so much that it resembles spaghetti. This means that it probably doesn’t have a star in it,” concludes Gillessen. “At the moment we think that the gas probably came from the stars we see orbiting the black hole.”

It’s an exciting time to be an astronomer. Through the “eyes” of the VLT, researchers the world over are able to watch a very unique event as it happens and not after the fact. ” This intense observing campaign will provide a wealth of data, not only revealing more about the gas cloud, but also probing the regions close to the black hole that have not been previously studied and the effects of super-strong gravity.”

As this drama at the heart of the Milky Way unfolds, astronomers are able to witness its many changes – “from purely gravitational and tidal to complex, turbulent hydrodynamics.”

Original Story Source: ESO News Release.