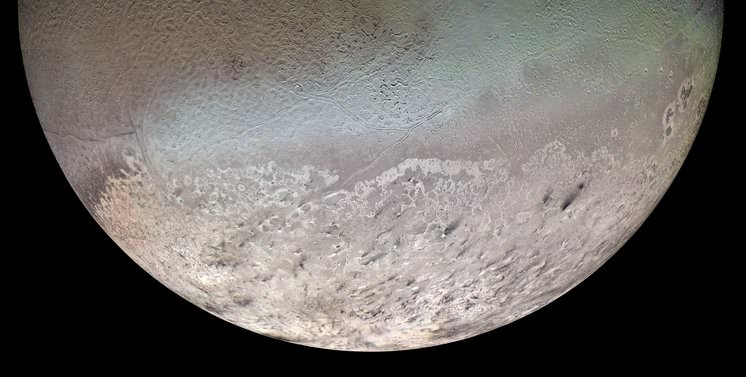

Voyager 2 mosaic of Neptune’s largest moon, Triton (NASA)

At 1,680 miles (2,700 km) across, the frigid and wrinkled Triton is Neptune’s largest moon and the seventh largest in the Solar System. It orbits the planet backwards – that is, in the opposite direction that Neptune rotates – and is the only large moon to do so, leading astronomers to believe that Triton is actually a captured Kuiper Belt Object that fell into orbit around Neptune at some point in our solar system’s nearly 4.7-billion-year history.

Briefly visited by Voyager 2 in late August 1989, Triton was found to have a curiously mottled and rather reflective surface nearly half-covered with a bumpy “cantaloupe terrain” and a crust made up of mostly water ice, wrapped around a dense core of metallic rock. But researchers from the University of Maryland are suggesting that between the ice and rock may lie a hidden ocean of water, kept liquid despite estimated temperatures of -97°C (-143°F), making Triton yet another moon that could have a subsurface sea.

How could such a chilly world maintain an ocean of liquid water for any length of time? For one thing, the presence of ammonia inside Triton would help to significantly lower the freezing point of water, making for a very cold — not to mention nasty-tasting — subsurface ocean that refrains from freezing solid.

In addition to this, Triton may have a source of internal heat — if not several. When Triton was first captured by Neptune’s gravity its orbit would have initially been highly elliptical, subjecting the new moon to intense tidal flexing that would have generated quite a bit of heat due to friction (not unlike what happens on Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io.) Although over time Triton’s orbit has become very nearly circular around Neptune due to the energy loss caused by such tidal forces, the heat could have been enough to melt a considerable amount of water ice trapped beneath Triton’s crust.

In addition to this, Triton may have a source of internal heat — if not several. When Triton was first captured by Neptune’s gravity its orbit would have initially been highly elliptical, subjecting the new moon to intense tidal flexing that would have generated quite a bit of heat due to friction (not unlike what happens on Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io.) Although over time Triton’s orbit has become very nearly circular around Neptune due to the energy loss caused by such tidal forces, the heat could have been enough to melt a considerable amount of water ice trapped beneath Triton’s crust.

Related: Titan’s Tides Suggest a Subsurface Sea

Another possible source of heat is the decay of radioactive isotopes, an ongoing process which can heat a planet internally for billions of years. Although not alone enough to defrost an entire ocean, combine this radiogenic heating with tidal heating and Triton could very well have enough warmth to harbor a thin, ammonia-rich ocean beneath an insulating “blanket” of frozen crust for a very long time — although eventually it too will cool and freeze solid like the rest of the moon. Whether this has already happened or still has yet to happen remains to be seen, as several unknowns are still part of the equation.

“I think it is extremely likely that a subsurface ammonia-rich ocean exists in Triton,” said Saswata Hier-Majumder at the University of Maryland’s Department of Geology, whose team’s paper was recently published in the August edition of the journal Icarus. “[Yet] there are a number of uncertainties in our knowledge of Triton’s interior and past which makes it difficult to predict with absolute certainty.”

Still, any promise of liquid water existing elsewhere in large amounts should make us take notice, as it’s within such environments that scientists believe lie our best chances of locating any extraterrestrial life. Even in the farthest reaches of the Solar System, from the planets to their moons, into the Kuiper Belt and even beyond, if there’s heat, liquid water and the right elements — all of which seem to be popping up in the most surprising of places — the stage can be set for life to take hold.

Read more about this here on Astrobiology.net.

Inset image: Voyager 2 portrait of Neptune and Triton taken on August 28, 1989. (NASA)

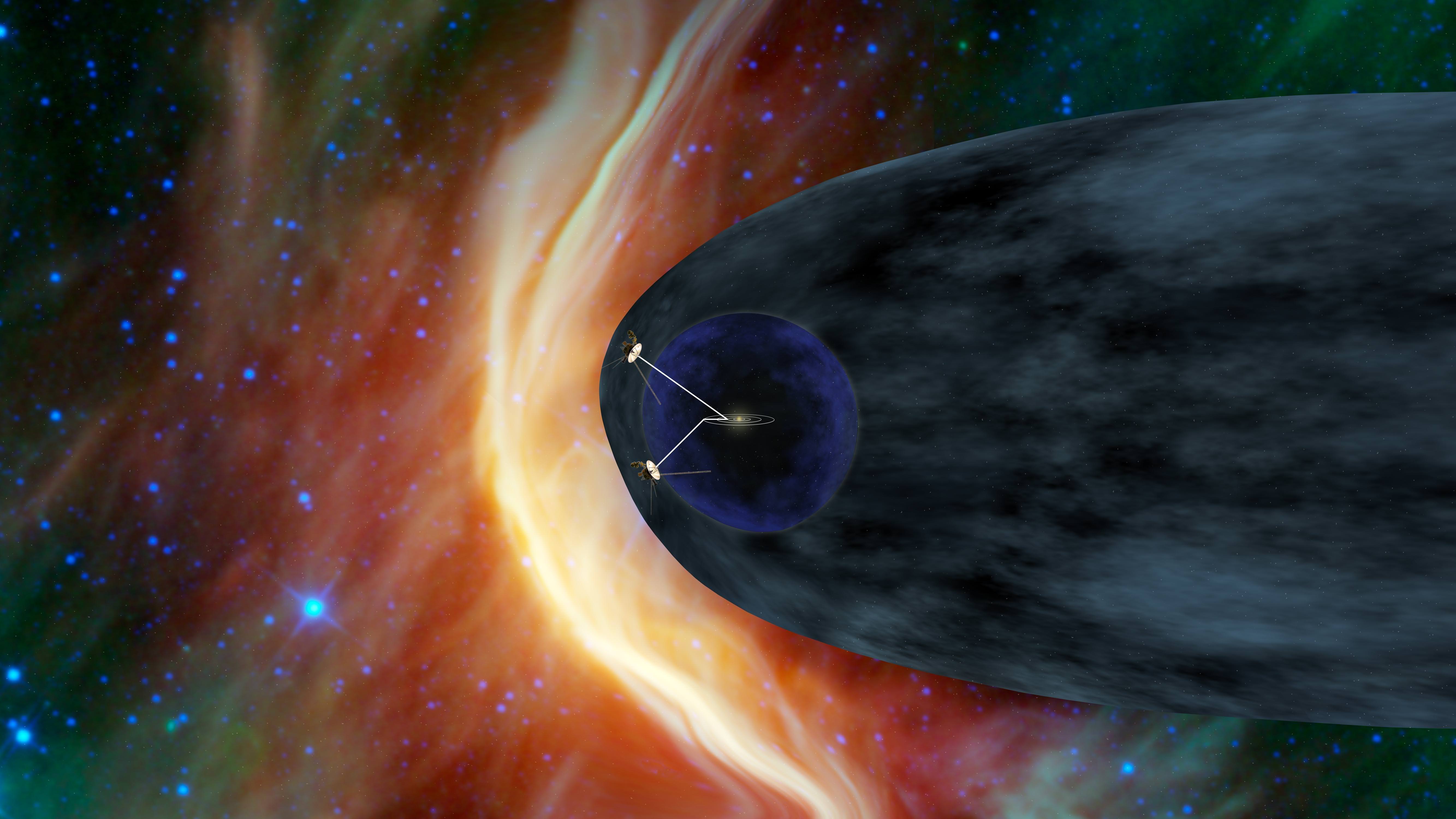

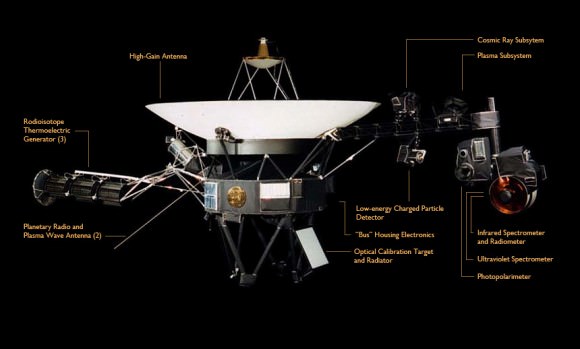

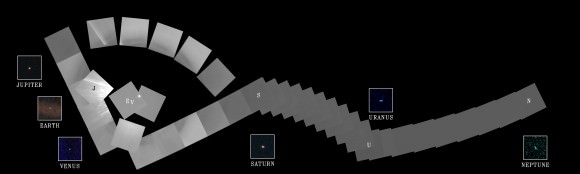

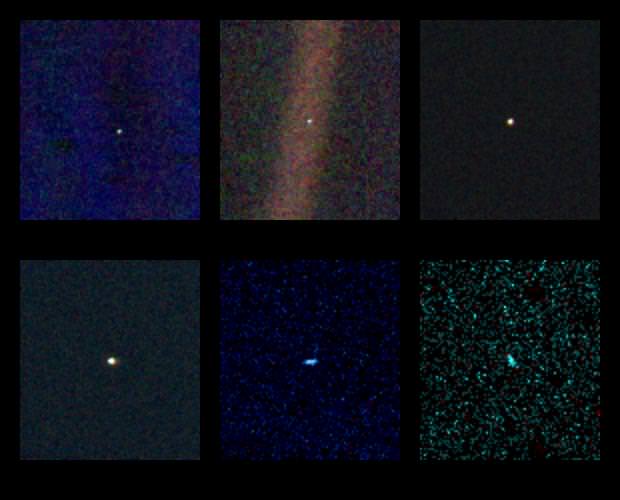

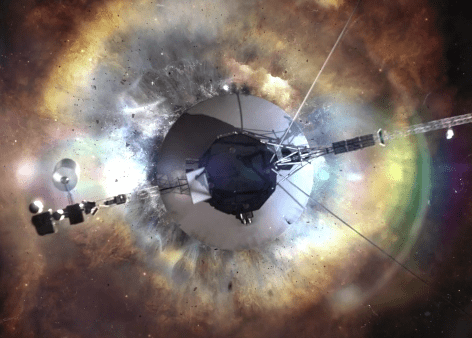

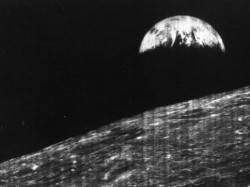

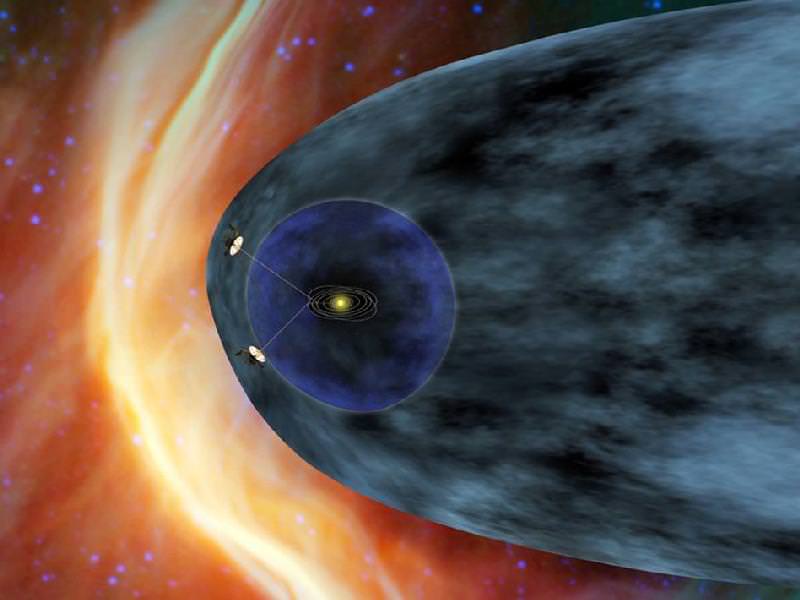

It was the unique perspective above provided by Voyager 1 that inspired Carl Sagan to first coin the phrase “Pale Blue Dot” in reference to our planet. And it’s true… from the edges of the solar system Earth is just a pale blue dot in a black sky, a bright speck just like all the other planets. It’s a sobering and somewhat chilling image of our world… but also inspiring, as the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft are now the farthest human-made objects in existence — and getting farther every second. They still faithfully transmit data back to us even now, over 35 years since their launches, from 18.5 and 15.2 billion kilometers away.

It was the unique perspective above provided by Voyager 1 that inspired Carl Sagan to first coin the phrase “Pale Blue Dot” in reference to our planet. And it’s true… from the edges of the solar system Earth is just a pale blue dot in a black sky, a bright speck just like all the other planets. It’s a sobering and somewhat chilling image of our world… but also inspiring, as the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft are now the farthest human-made objects in existence — and getting farther every second. They still faithfully transmit data back to us even now, over 35 years since their launches, from 18.5 and 15.2 billion kilometers away.

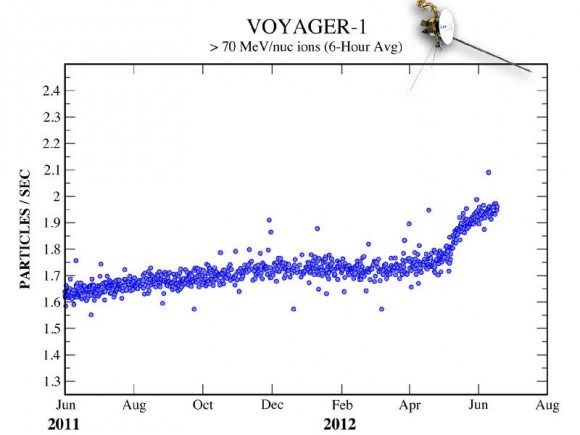

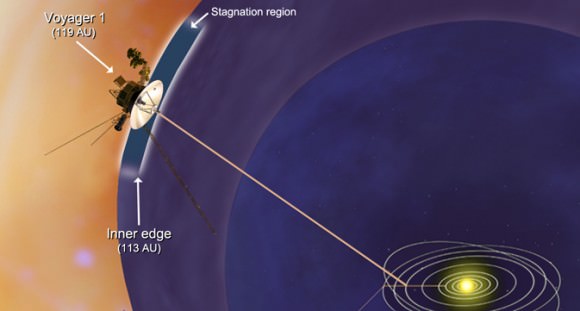

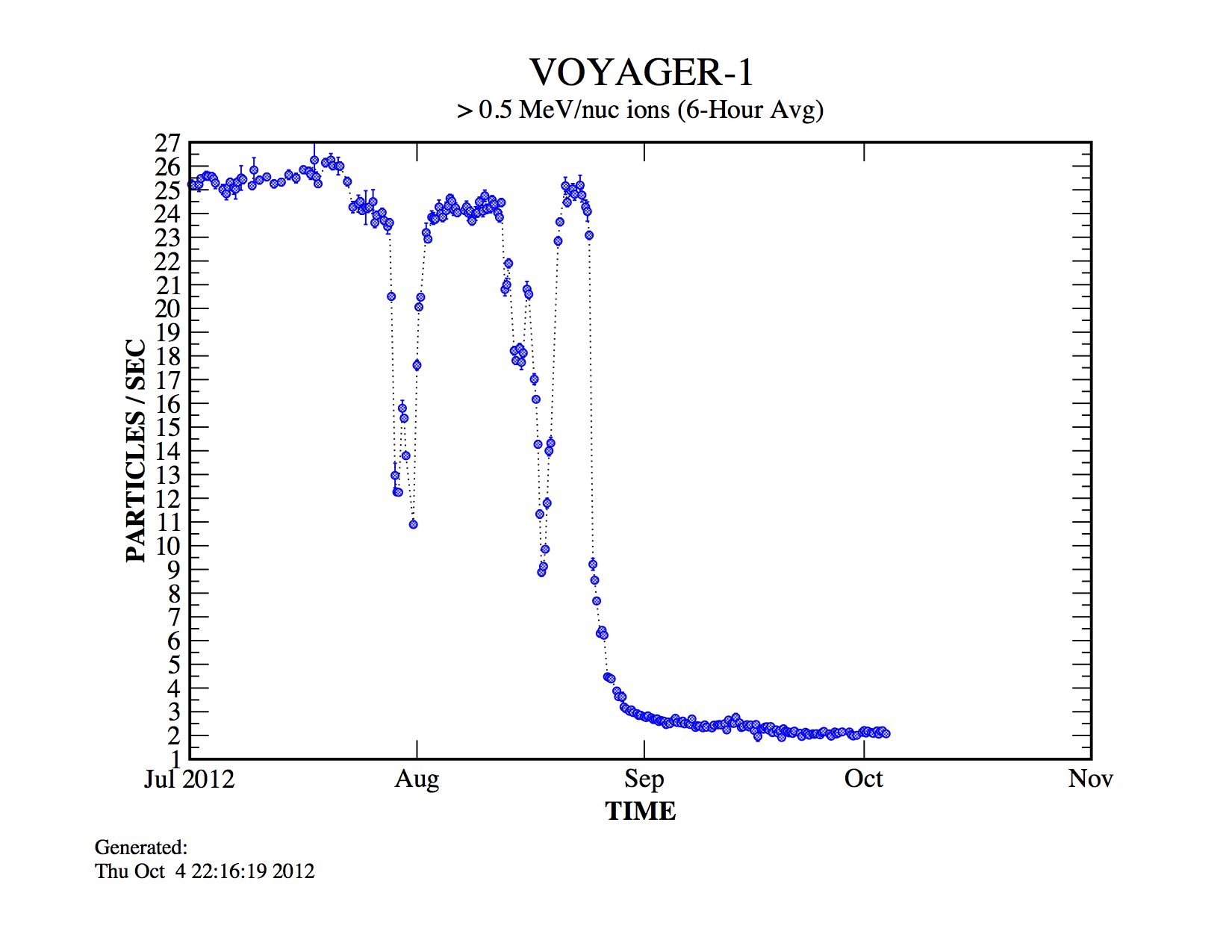

Data sent from Voyager 1 — a trip that currently takes the information nearly 17 hours to make — have shown steadily increasing levels of cosmic radiation as the spacecraft moves farther from the Sun. But on July 28, the levels of high-energy cosmic particles detected by Voyager jumped by 5 percent, with levels of lower-energy radiation from the Sun dropping by nearly half later the same day. Within three days both levels had returned to their previous states.

Data sent from Voyager 1 — a trip that currently takes the information nearly 17 hours to make — have shown steadily increasing levels of cosmic radiation as the spacecraft moves farther from the Sun. But on July 28, the levels of high-energy cosmic particles detected by Voyager jumped by 5 percent, with levels of lower-energy radiation from the Sun dropping by nearly half later the same day. Within three days both levels had returned to their previous states.