The study of extra-solar planets has revealed some fantastic and fascinating things. For instance, of the thousands of planets discovered so far, many have been much larger than their Solar counterparts. For instance, most of the gas giants that have been observed orbiting closely to their stars (aka. “Hot Jupiters”) have been similar in mass to Jupiter or Saturn, but have also been significantly larger in size.

Ever since astronomers first placed constraints on the size of a extra-solar gas giant seven years ago, the mystery of why these planets are so massive has endured. Thanks to the recent discovery of twin planets in the K2-132 and K2-97 system – made by a team from the University of Hawaii’s Institute for Astronomy using data from the Kepler mission – scientists believe we are getting closer to the answer.

The study which details the discovery – “Seeing Double with K2: Testing Re-inflation with Two Remarkably Similar Planets around Red Giant Branch Stars” – recently appeared in The Astrophysical Journal. The team was led by Samuel K. Grunblatt, a graduate student at the University of Hawaii, and included members from the Sydney Institute for Astronomy (SIfA), Caltech, the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, the SETI Institute, and multiple universities and research institutes.

Because of the “hot” nature of these planets, their unusual sizes are believed to be related to heat flowing in and out of their atmospheres. Several theories have been developed to explain this process, but no means of testing them have been available. As Grunblatt explained, “since we don’t have millions of years to see how a particular planetary system evolves, planet inflation theories have been difficult to prove or disprove.”

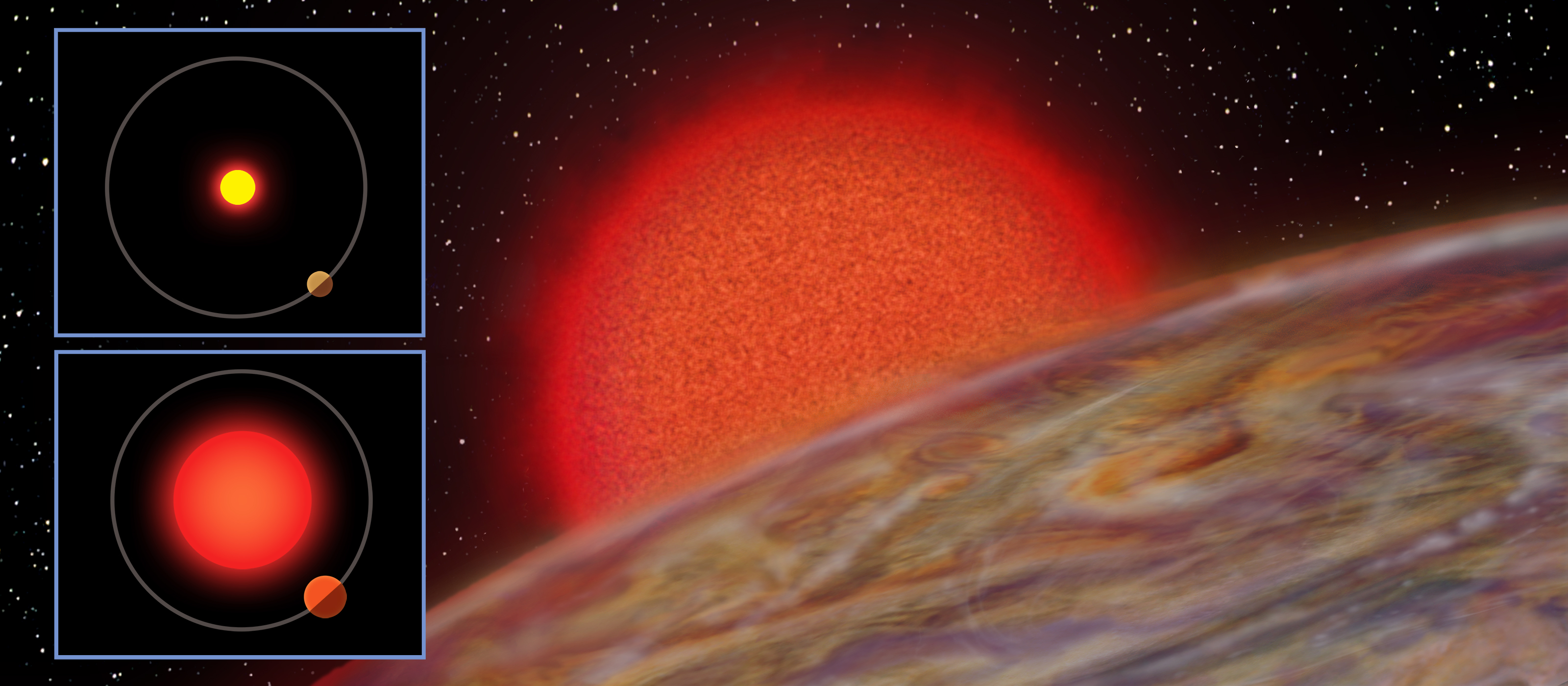

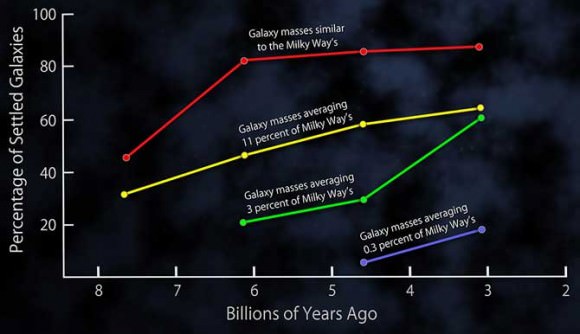

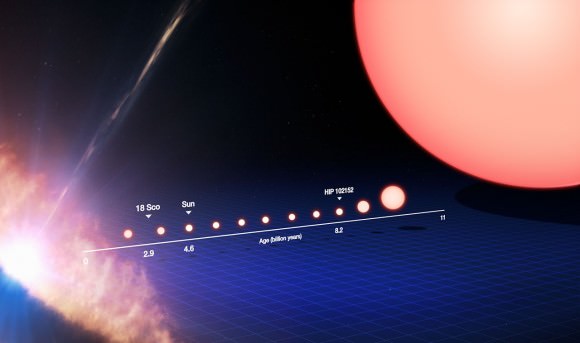

To address this, Grunblatt and his colleagues searched through the data collected by NASA’s Kepler mission (specifically from its K2 mission) to look for “Hot Jupiters” orbiting red giant stars. These are stars that have exited the main sequence of their lifespans and entered the Red Giant Branch (RGB) phase, which is characterized by massive expansion and a decrease in surface temperature.

As a result, red giants may overtake planets that orbit closely to them while planets that were once distant will begin to orbit closely. In accordance with a theory put forth by Eric Lopez – a member of NASA Goddard’s Science and Exploration Directorate – hot Jupiter’s that orbit red giants should become inflated if direct energy output from their host star is the dominant process inflating planets.

So far, their search has turned up two planets – K2-132b and K2-97 b – which were almost identical in terms of their orbital periods (9 days), radii and masses. Based on their observations, the team was able to precisely calculate the radii of both planets and determine that they were 30% larger than Jupiter. Follow-up observations from the W.M. Keck Observatory at Maunakea, Hawaii, also showed that the planets were only half as massive as Jupiter.

The team then used models to track the evolution of the planets and their stars over time, which allowed them to calculate how much heat the planets absorbed from their stars. As this heat was transferring from their outer layers to their deep interiors, the planets increased in size and decreased in density. Their results indicated that while the planets likely needed the increased radiation to inflate, the amount they got was lower than expected.

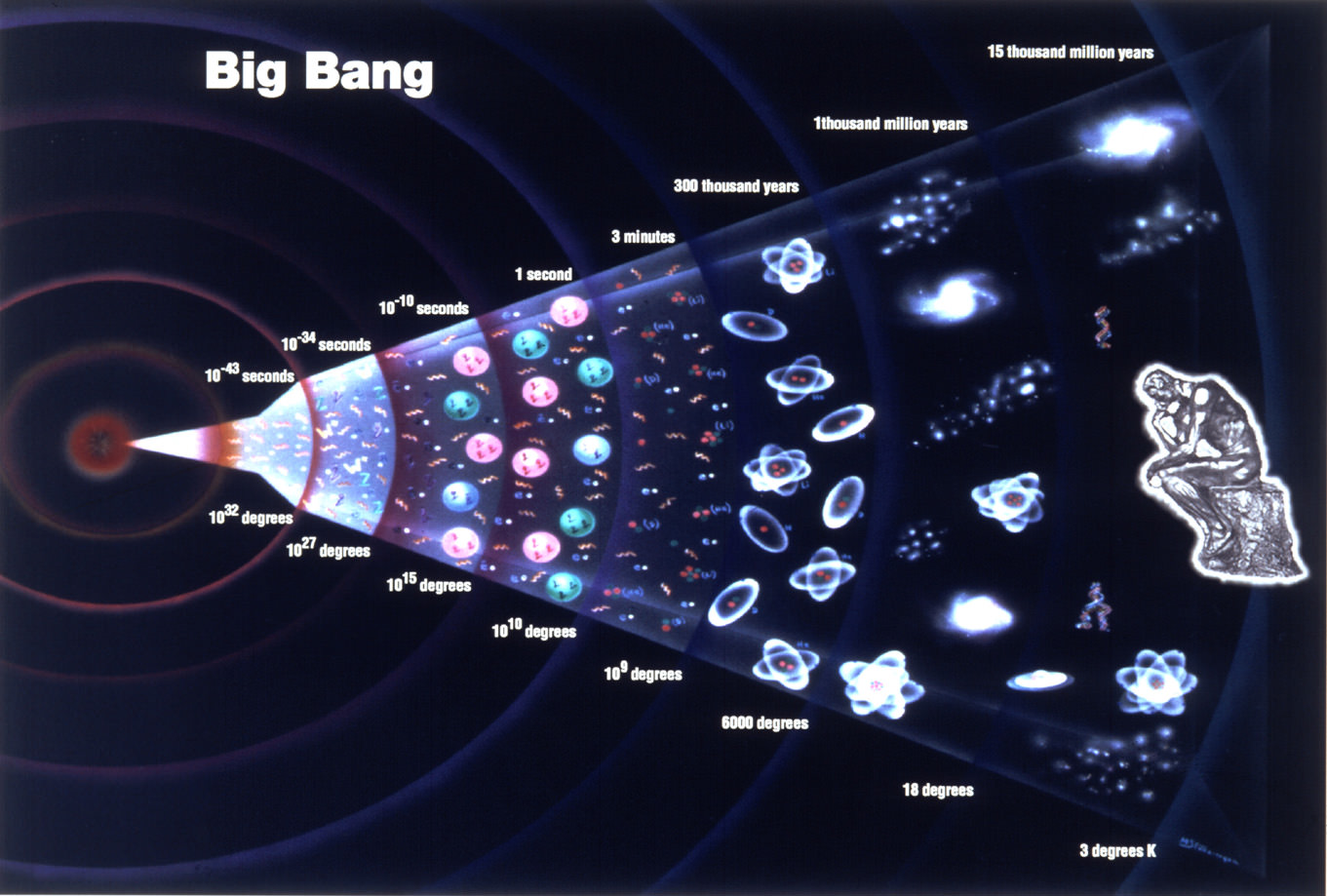

While the study is limited in scope, Grunblatt and his team’s study is consistent with the theory that huge gas giants are inflated by the heat of their host stars. It is bolstered by other lines of evidence that hint that stellar radiation is all a gas giant needs to dramatically alter its size and density. This is certainly significant, given that our own Sun will exit its main sequence someday, which will have a drastic effect on our system of planets.

As such, studying distant red giant stars and what their planets are going through will help astronomers to predict what our Solar System will experience, albeit in a few billion years. As Grunblatt explained in a IfA press statement:

“Studying how stellar evolution affects planets is a new frontier, both in other solar systems as well as our own. With a better idea of how planets respond to these changes, we can start to determine how the Sun’s evolution will affect the atmosphere, oceans, and life here on Earth.”

It is hoped that future surveys which are dedicated to the study of gas giants around red giant stars will help settle the debate between competing planet inflation theories. For their efforts, Grunblatt and his team were recently awarded time with NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, which they plan to use to conduct further observations of K2-132 and K2-97, and their respective gas giants.

The search for planets around red giant stars is also expected to intensify in the coming years with he deployment of NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). These missions will be launching in 2018 and 2019, respectively, while the K2 mission is expected to last for at least another year.

Further Reading: IfA, The Astronomical Journal